Barberini Museum, Potsdam

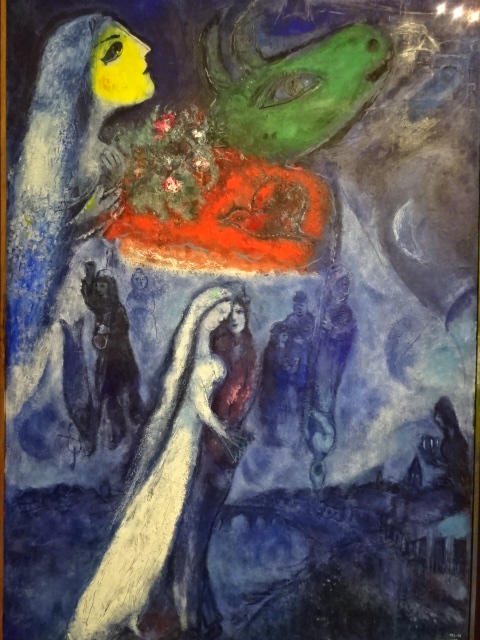

During 2025 I visited many art exhibitions, and each one opened up a new world for me, giving me a new perspective on the time periods represented in the shows. I took two days trips abroad. I went to the Barberini Museum in Potsdam to see temporary exhibitions of works by Wassily Kandinsky and another of paintings by Camille Pissarro. I especially liked Kandinsky’s early works, in which color played such a symbolic role. Vasari, Stella and Mondrian were also represented.

Camille Pissarro, The Garden of Les Mathurins at Pontoise, 1876, Postcard from exhibition.

The Pissarro exhibition was close to my heart. I was overwhelmed by his landscapes, some punctuated by workers in the fields. His early Caribbean scenes and his renditions of Paris made significant impressions on me. His bold and vivacious colors amazed me and gave me a sense of serenity about the often chaotic and problematic world.

Claude Monet, Villas at Bordighera, 1884, Postcard

I loved the permanent exhibition at the Barberini with its vast Impressionist collection that included 40 works by Claude Monet, one of my favorite all-time artists. Most fascinating for me were Monet’s landscapes of Bordighera, Italy and his renditions of Venice. Paintings by Alfred Sisley and Auguste Renoir also captured my undivided attention. I was overwhelmed by the astounding Impressionist art in this museum. Seeing the permanent collection was a dream come true.

An early rendition of the palace in Potsdam

Potsdam City Museum, painting of the Third Reich era

Nearby was the Museum of the City of Potsdam, which I visited twice. I saw the developments of the city via paintings of villas, monuments and the luxurious palace from the glorious era of Frederick III. The furnishings and objects that accompanied each historical display were poignant. I especially was drawn to the exhibitions on the city during the Nazi and Communist eras.

Potsdam, Church of Saint Nicholas

Potsdam, interior of the Church of Saint Nicholas

I also visited Saint Nicholas’ Church across the square from the museum. Its colorful frescoes inside represented the Evangelists and Apostles. The exterior featured Corinthian columns, and the church stood 42 meters high. The reconstruction after World War II was laudable. In addition, I saw the Dutch section of Potsdam. It resembled a backdrop of a Vermeer painting.

Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna, Pieter Bruegel the Elder, Hunters in the Snow

Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna, work by the Bassano family

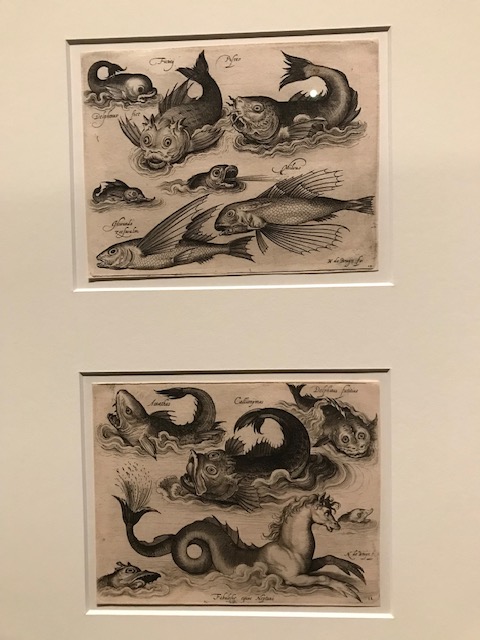

At the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna, Austria I enjoyed the exhibition of works by Pieter Bruegel the Elder, the Bassano family and Giuseppe Arcimboldo along with some by the master of North Renaissance style Albrecht Durer. Bruegel the Elder is my all-time favorite (along with Monet) painter. I loved his landscapes, peasant scenes and religious works. His attention to detail was amazing as the many figures in his paintings were all engaged in various activities. The Kunsthistorisches Museum was known for their permanent collection of his Dutch Renaissance renditions. Arcimboldo, who worked for Habsburg emperors, was a significant painter in the 16th century Italian Mannerist style. He is best known for his unique portrait heads made of objects, such as fruit, vegetables, flowers and fish. His works were the epitome of the grotesque, and nature was a recurrent theme in his paintings. The High Renaissance style was visible in his portrait heads, too.

Giuseppe Arcimboldo, portrait of a head

By Albrecht Durer during the German Renaissance

A prominent painter during the German Renaissance, Durer was a master at engravings, prints and watercolors, for instance. I loved his still lifes of nature as well as his portrayal of praying hands.

Kunstkammer, Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna

Kunstkammer, Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna

I also gazed at the artifacts in the permanent exhibitions – Egyptian and near Eastern art, Greek and Roman antiquities and masterpieces of European painting, such as those by Vermeer and Rembrandt. The Kunstkammer world of curiosities focused on gold, silver and ivory objects as well as paintings, sculptures, scientific instruments and miniatures. The art showed off a variety of styles courtesy of the Habsburg rulers. I couldn’t resist a cappuccino in the museum’s restaurant, permeating with a sense of grandeur as well as elegance. The restaurant was a work of art in itself.

Ivana Bachová, 1995, Fairy Pools

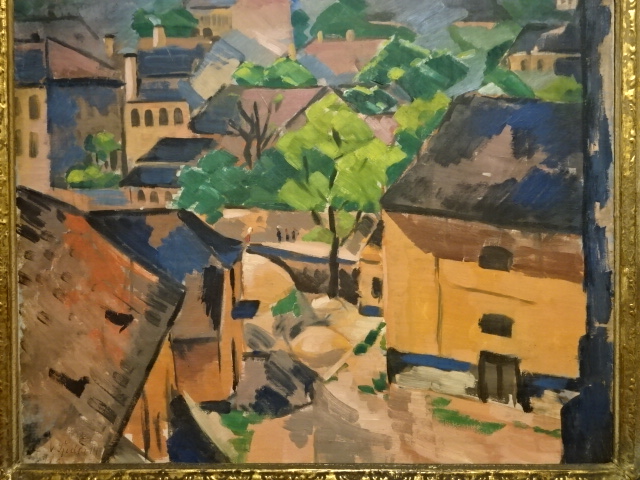

Jiří Kars, French Landscape, 1910-1914

Back in Prague, I went to another exhibition of 19th and 20th century Czech art at the Kooperativa Gallery, an intimate space located in an office building. The landscapes enthralled me, especially the French landscape by Jiří Kars. Artists Otakar Lebeda, Amálie Mánesová and Vojtěch Preissig were just a few of the painters represented in the thrilling exhibition. Sculptures by Ladislav Janouch and Jaroslav Horejš also were on display.

Václav Špála, Mill at Otava, 1929

Jan Zrzavý, Madonna, 1930

Also at the Kooperativa during 2025 was a stunning exhibition of modern 20th century art. Václav Špála’s brilliant blues caught my attention in his rendition of a mill at Otava from 1929. Jan Zrzavý’s elements of Primitivism awed me in his Madonna from 1930. Vincenc Beneš’ view of Kampa Island and Preissig’s rendition of a village also enthralled me.

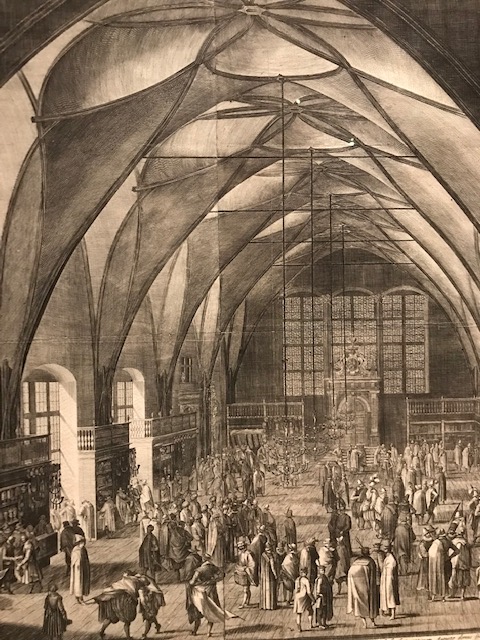

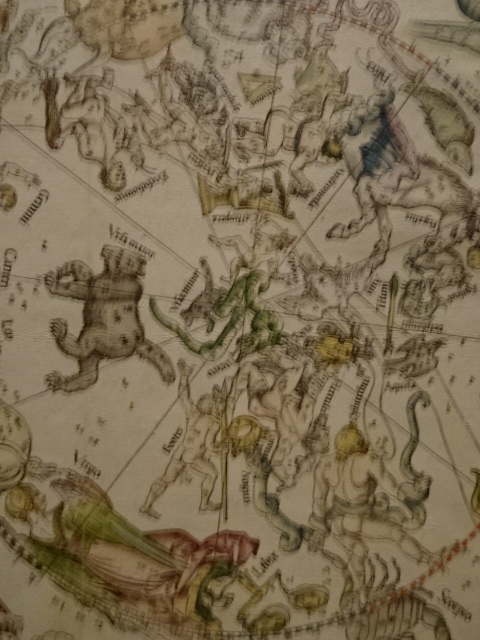

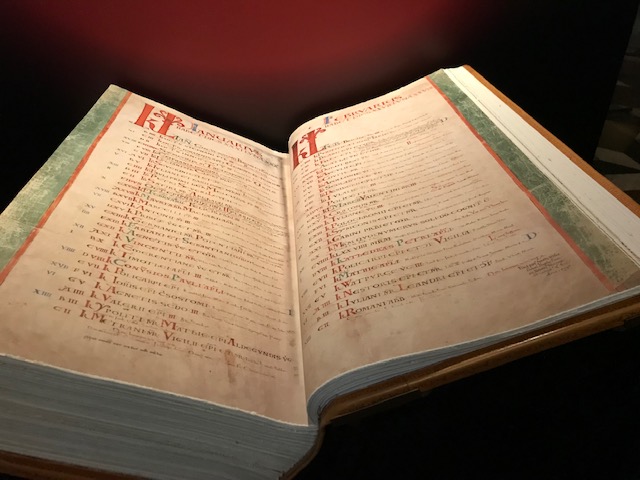

Cosmas Chronicle

At the chapel in the Clementinum, I viewed various editions of the Cosmas Chronicle, one of the most important books in Czech history, These medieval manuscripts narrated stories about Czech rulers of Bohemia and Moravia, for example. It remains the most significant story of the Czechs told through a historical lens. The oldest, the Chronicle of Leipzig, hailed from the 12th century while the Chronicle of Vienna dated from the 13th century.

National Museum, 100 Treasures, 100 Stories exhibition of artifacts from Chinese emperors

The illustrated manuscripts enthralled me. Each one was unique and remarkable. I have always been fascinated by illustrated manuscripts. (One of the highlights of my visit to Dublin, in fact, was seeing the Book of Kells and the manuscripts at the Chester Beatty Library Museum.) With a master’s in Czech literature, I am very enamored by Czech medieval works and could stare at them for hours, if allowed.

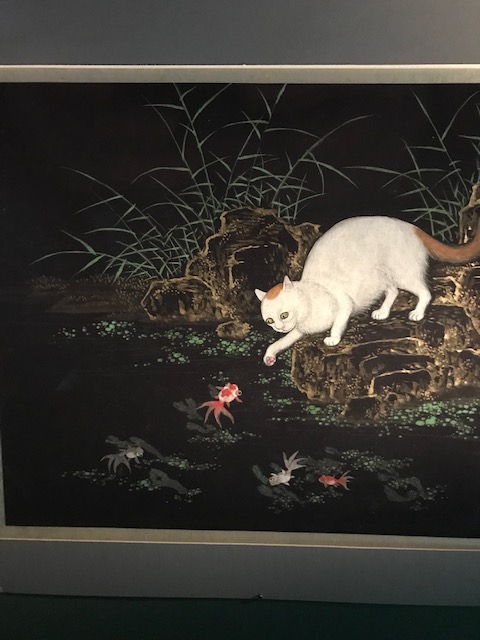

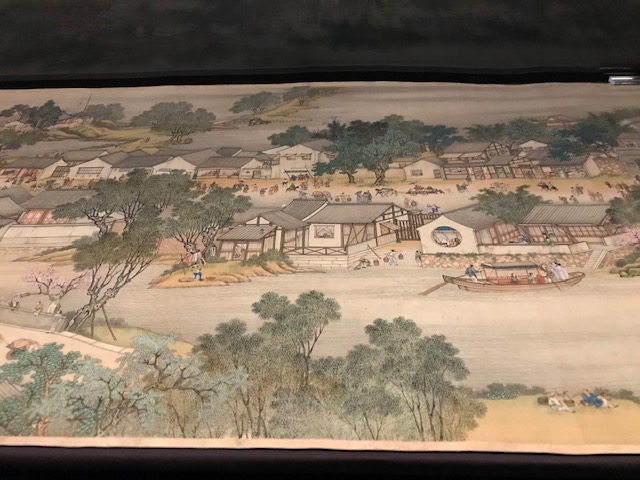

National Museum, 100 Treasures, 100 Stories

I also made a trip to the National Museum on Wenceslas Square. I saw the “100 Treasures, 100 Stories” exhibition on artifacts from the dynasties of Chinese emperors. The paintings and figurines of cats were my favorite. I also loved the renditions of villas, the sea and scenes from daily life during the eras of the emperors. The objects with dragons and elephants also enthralled me.

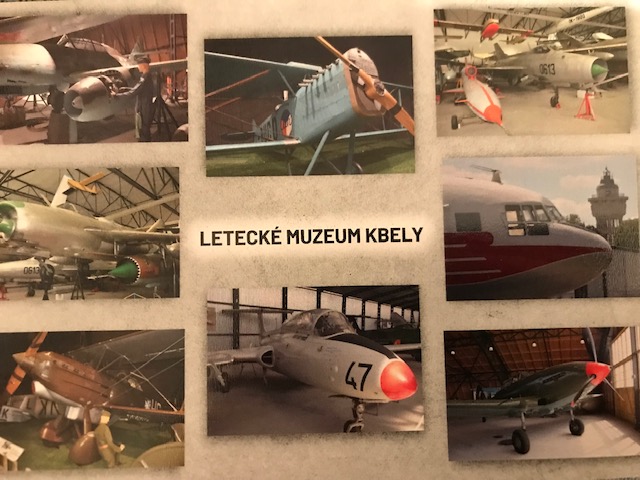

Military Aviation Museum, Kbely, Postcard

A vast museum that I visited for the first time was the Military Aviation Museum in the Kbely district of Prague. I was fascinated by the contents of the five large hangars – the war planes, the show planes, the training planes, the passenger planes. There was so much to see from so many eras. I was most drawn to the planes and bicycles from World War I. It was so intriguing to see how aviation had developed in the military sphere ever since the first planes were designed. One of the most significant objects for me was the space capsule in which a Czech astronaut had returned to Earth during the 1970s. The American Douglas planes also were very noteworthy. The sleek modern military helicopters also gave me sense of awe.

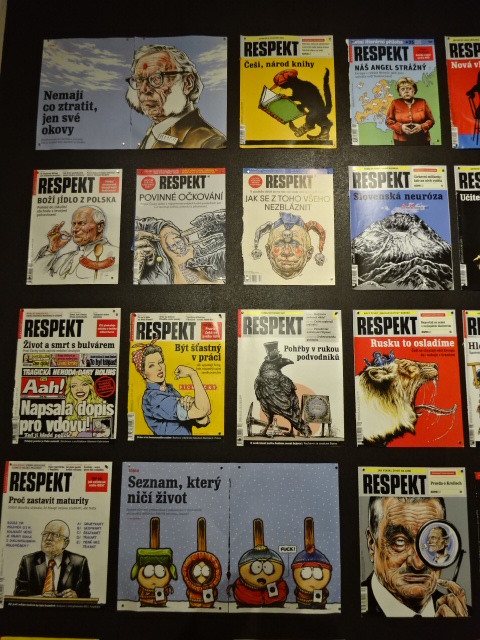

Covers of the magazine Respekt, Pavel Reisenauer

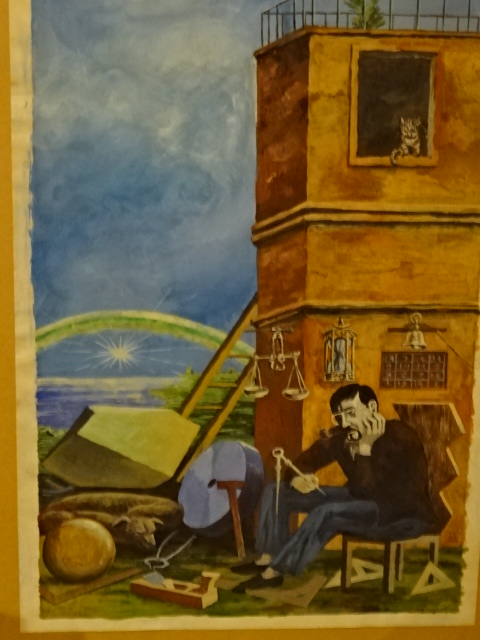

Painting by Pavel Reisenauer

The Kampa Museum in Prague hosted amazing exhibitions this past year. I admired paintings, photos, drawings, illustrations and covers of the magazine Respekt as well as his art for Lidové noviny’s supplement Orientace by the late Pavel Reisenauer. His paintings captured so many themes, including the periphery of Prague, solitude and emptiness. His magazine covers prominently commented on political and societal topics of the well-reputed magazine.

Václav Špála, The roofs of Malá strana

Emil Filla painting

Kampa also showed off the permanent collection of a Pilsen art gallery with significant Cubist works, such as those by Bohumil Kubišta and Špála, who painted the roofs of Malá strana with such excellence. Kubišta’s colorful religious works played a prominent role in the exhibition. Sculpture by Otto Gutfreund, such as his tortured Hamlet, was not lost upon me, either. Because there are often temporary exhibitions at this Pilsen gallery, the permanent collection is not often on display. One floor was filled with mythological paintings and still lifes by the stellar artist Emil Filla. I saw monsters in his works representing the dangers of Nazism and other grotesque figures playing prominently in his renditions. I especially enjoyed seeing the characteristics of Fauvism in Filla’s works.

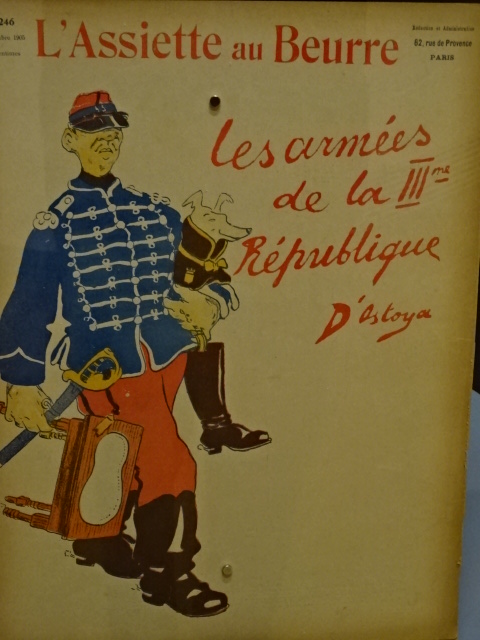

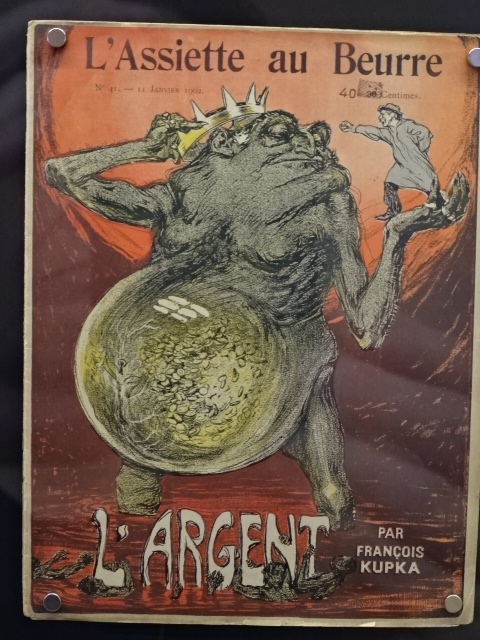

Caricatures from French magazines, created by František Kupka, made up another exhibition at Kampa Museum. The publications were printed at the end of the 19th century and beginning of the 20th century. Through grotesque images, such as those of monkeys, I came to understand better the political and societal tensions in France and in the world.

Salvidor Dali painting in Eye to Eye exhibition

Franz Kafka by Andy Warhol

Another exhibition that I admired at Kampa was the “Eye to Eye” show of works with motifs of eyes. I saw how the eye can symbolize the soul and be an open door to the internal world. Vision was sometimes portrayed as a religious miracle. I was so moved by the paintings at this exhibition. The portrait of a curious Franz Kafka by Andy Warhol was one of many that affected me. Two works by Salvidor Dali also held my attention. Czech artists such as Toyen, František Muzika and Antonín Hudeček were represented, too. Sculpture by Karel Nepráš and Ladislav Zívr also were moving. A distorted head by Picasso was another masterpiece.

From Wunderkammer by Orhan Pomuk

At the contemporary art museum DOX, I was fascinated by the Cabinet of curiosities or Wunderkammer designed by famous writer Orhan Pomuk. The three-dimensional works in collage form told the story of Istanbul from 1950 to 2000 as well as events in Turkish history. I learned about the history of a country I knew little about. I had had no idea that Pomuk’s talent included more than writing.

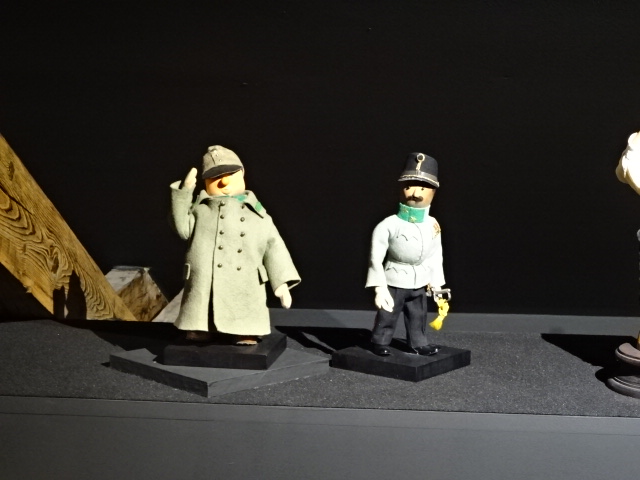

A puppet of the Good Soldier Švejk saluting

By Jiří Trnka

At the Villa Pellé there was an astounding exhibition of the art of Jiří Trnka, who had been a puppet maker, sculptor, painter and director of animated film. He also held the distinction of being the co-founder of Czech animated film. I especially enjoyed seeing the puppet of the Good Soldier Švejk, based on the antimilitaristic, novel by Jaroslav Hašek, a Czech class that took place during the Austro-Hungarian Empire. The humor and satire in the book are brilliant and profound.

Yet Trnka was known for so much more than his masterful puppetry. I loved his paintings of a fantastical, dreamy and fairy tale-like world. I admired his utilization of the grotesque in his sculptures and paintings. Illustrations from children’s books also were prominently displayed. I saw depictions from American, British and Czech fairy tales, for instance. I especially admired the illustrations from Trnka’s own book, The Garden, in which gnomes, bespectacled whales and naughty cats made appearances. His illustrations for Jan Werich’s children’s book Finfarum were very noteworthy, too.

Amálie Mánesová, Vrbičany Chateau, 1846

Cheb Antependium from Přemyslid Dynasty era

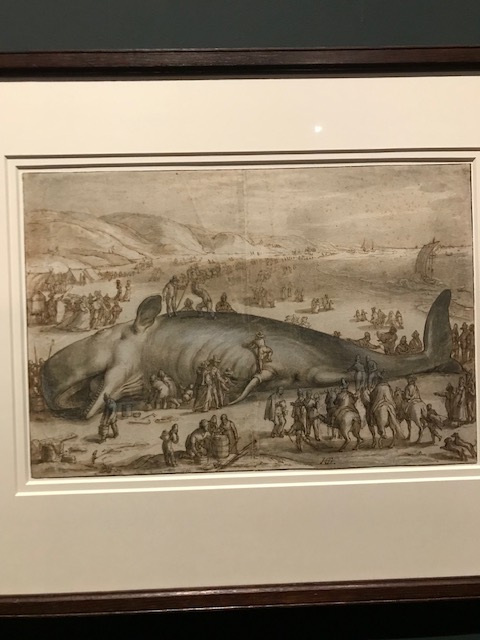

One excellent exhibition at the Wallenstein Riding Stables venue was a comprehensive showcase of women in art from 1300 to 1900. I marveled at the medieval works, tapestries, portraits and landscapes, for instance. I was drawn to the paintings of Venice’s Bridge of Sighs and the Ducal Palace because of my love for Italy. The religious Italian art was intense and dynamic. The prints from the 16th and 17th centuries made strong impressions on me, too. One Dutch painting influenced by the work of Frans Hals stood out for me, too. My favorites were the renditions by Amálie Mánesová, who hailed from the legendary Mánes family. Her painting of a chateau with landscape and her portraits were especially to my liking.

From Silent Spring Exhibition, František Kupka, Tale of Pistils and Stamens I, 1919-20

From Silent Spring Exhibition, Anna Hulačová, After Bugonia, 1984

At the Trade Fair Palace, I saw the exhibition “Silent Spring” about man’s relationship with nature from 1930 to 1970 and beyond. The surrealistic paintings and abstract sculpture from the 1960s captured my undivided attention. I also perused the permanent exhibition “The Long Century,” which focused on artistic tendencies from 1796 to 1918. Portraits of artists, landscapes, sculpture and art with a theme of the progress in transportation all were very moving. I especially was thrilled by František Bílek’s sculpture “The Blind Leading the Blind” This colossal work always made a strong impression on me. Auguste Rodin’s sculpture also enthralled me. Paintings by Monet, Pablo Picasso and Paul Signac greatly influenced me as did the works by many Czech artists.

From The Long Century, František Bílek, The Blind Leading the Blind

From the Long Century, Jakub Schikander, Early Evening at Hradčany, 1910-1915

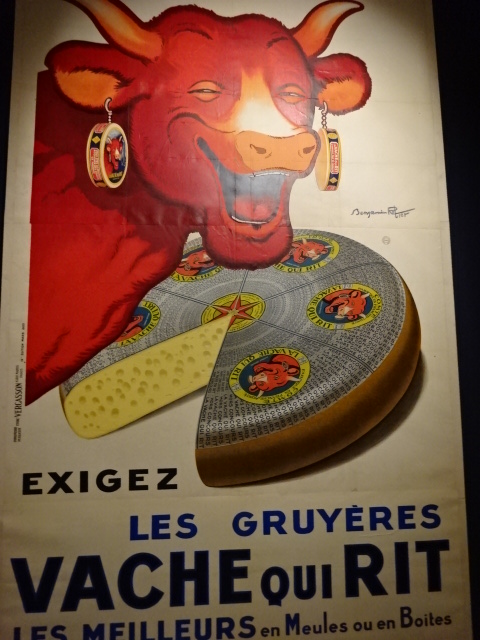

At the end of 2025, I visited an exhibition of French advertising posters from the 1920s and 1930s at the Museum of Decorative Arts in Prague. The 25 posters were bold, vivacious, grotesque and humorous. Many utilized caricature. I saw posters advertising progress in forms of transportation – trains, planes and ships. The travel posters were close to my heart. I gazed at the beaches of France and a townscape of Nice, for instance. I recognized the ad for cheese promoted by a gigantic red cow. The glass designs in the permanent exhibition at the museum also captured my attention. The dresses, shoes, ties and other garments were noteworthy. The interior of the building itself with stunning paintings on the walls and ceiling gave the museum such personality and a sense of grandeur.

I was thrilled with all the exhibitions that helped shape my year in a positive way. The exhibitions gave me solace and hope during a year riddled with sadness despite the excellent cultural events I experienced. Gazing at the art filled my heart with joy and gave me mental strength. I was thankful that I had been able to see so many influential exhibitions during 2025.

Museum of Decorative Arts, Prague

Museum of Decorative Arts, Prague

Museum of Decorative Arts, Prague

Museum of Decorative Arts, Prague

Museum of Decorative Arts, Prague

Museum of Decorative Arts, Prague

Museum of Decorative Arts, Prague