During the summer and fall of 2024, the West Bohemian Gallery in Pilsen showed off the riveting exhibition “Through the Eyes of Franz Kafka: Between Picture and Language.” It focused on the ways in which the visual world around Kafka had been influential in the language Kafka chose for his writings. There was a direct connection between the visual world and the literary world in Prague, Kafka would have seen the works on display in his everyday Prague life that boasted of a multilingual society immersed in the languages of Czech, German and Hebrew. Kafka resided in Prague his entire life – from July 3, 1883 to June 3, 1924, when he died at the age of 40 from tuberculosis. He spoke German as well as Czech and wrote in German. His parents spoke German mingled with Yiddish.

At the end of the 19th and beginning of the 20th century, posters were displayed all over the city. Designed in the Art Nouveau style, they showed off art exhibitions, cabaret shows, literary events, advertisements and much more. Japanese art played a role in the decoration of these posters. Later, the artistic focus was Cubist features. German-Czech spiritualism also was influenced by the time period. Silent films, both European and American, were popular in Prague. Going to the cabaret, ballet and theatre were pastimes of Praguers.

Exhibition Wordwede in Kinská Garden, Prague, 1903.

Modern French Art exhibition, Kinská Garden, Prague, 1902.

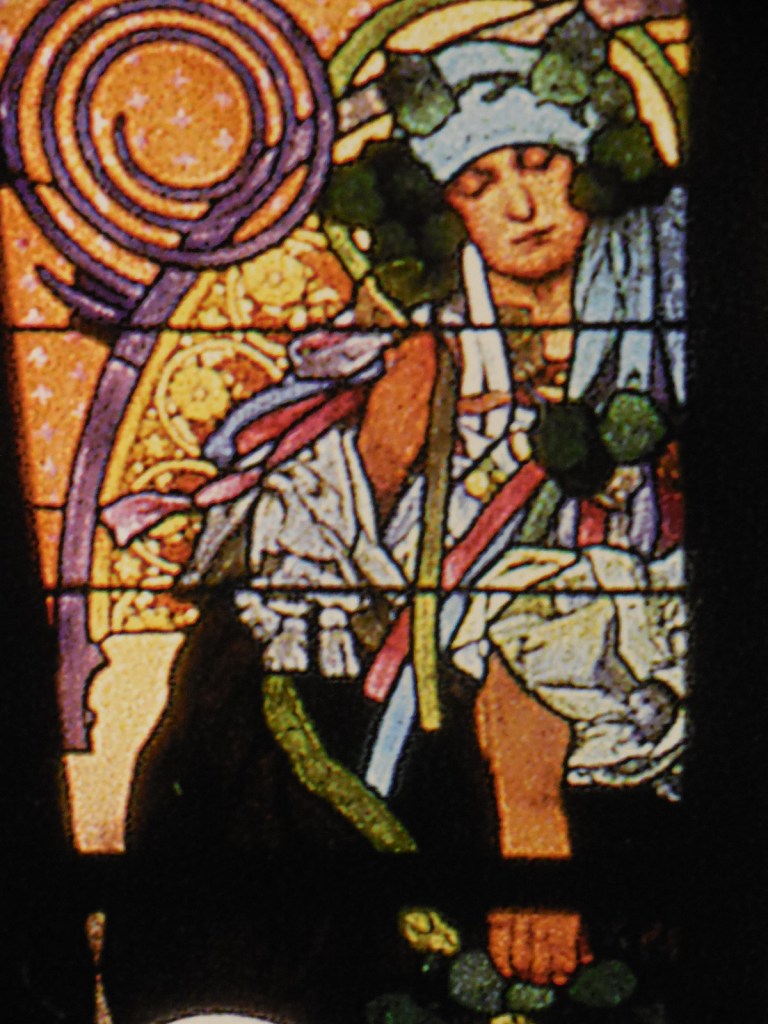

I would like to highlight several of the artists represented in the show, including the posters of Jan Preisler, a Czech painter and university professor. For a while his works promoted the Art Nouveau style, which is evident in this poster for an art exhibition. He also decorated Art Nouveau buildings in Prague. For example, the Hotel Central in Prague features his ornamentation. The triptych Spring was made for the Peterka building in the capital city. Preisler made a name for himself as a Secession artist, even though he would take on a different style later in his career.

Girl in Flowers, 1922, by Anton Bruder

Many of his works could be designated as Neo-Romantic, punctuated with allegorical Symbolism. His art often showed a fondness for fairy tales or moods characterized by depression and sadness. Preisler attempted to reveal the depth of one’s soul. Early in his career he became friends with Czech landscape painter Antonín Hudeček. Preisler was also influenced by the art of Edvard Munch as he helped plan the 1905 exhibition of Munch’s depictions in Prague. Preisler also had developed friendships with painters Bohumil Kubišta and Vincenc Beneš. He was very inspired by the poetry of Otakar Březina, a Czech artist who wrote in a complex, symbolist style and was nominated for the Nobel Prize eight times. Vitezslav Nezval and Josef Suk were other poets who made an impression on him. Perhaps his best known painting is the triptych “Spring,” from the turn of the century. It depicted the complex feelings of someone entering the 20th century. Man experienced a nostalgia for the past, but, at the same time, was looking forward to adventures awaiting him in the new century. A person’s connection to nature was another theme promoted in this triptych.

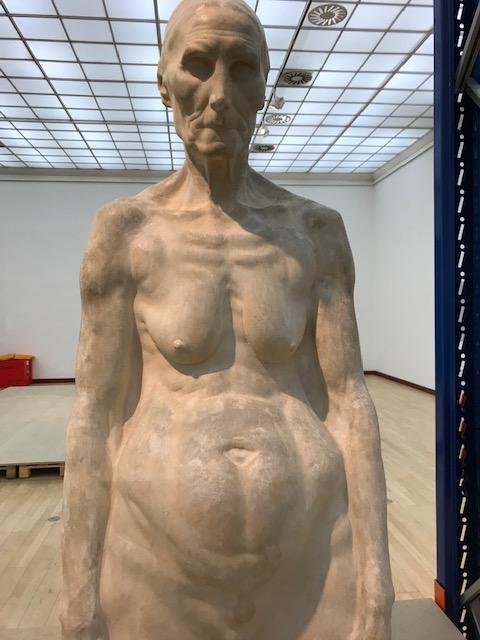

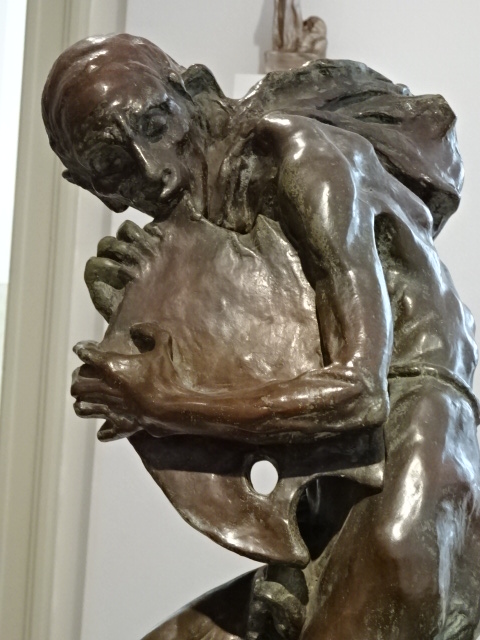

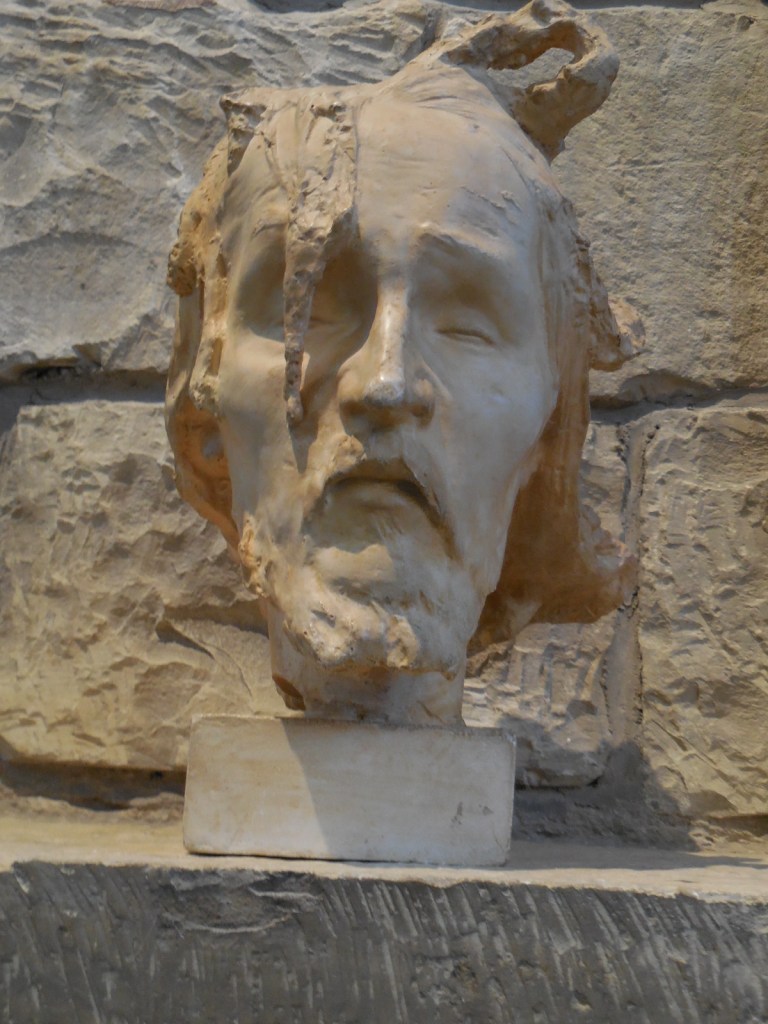

Sculpture by František Bílek

Jan Žižka, by František Bílek, 1912

Sculpture that permeated the exhibition included that of Art Nouveau symbolist František Bílek, whose Secession homes in Prague and Chýnov I had visited. Miniature versions of several of his sculptures were on display. He utilized mostly religious themes with a sense of mysticism. While Bílek was best known as a sculptor, he also designed furniture and created graphic art, drawings and illustrations. An architect as well, he designed cemeteries and made gravestones, for instance. His woodcarving skills were astounding, too. A year later, in 2025, I would see Bílek’s amazing works in the former flat of Czech poet Otakar Březina, incorporated into a museum for the symbolist poet in Jaroměřice of the Vysočany region. To be sure, Bílek’s creations caught the attention of society during the Art Nouveau age.

The Interior, by Bohumil Kubišta, 1908

One of my favorite Czech painters of this period, Bohumil Kubišta played a role in the exhibition. One of the first to paint in a modern Czech style, Kubišta created a new path for artists as he helped establish the significant Osma group of painters who were oriented toward Munch’s style. In Kubišta’s paintings, bright color played a large role as did mysticism and symbolism. At times he took up religious themes. Kubišta often concentrated on the spiritual as the symbolism of life and death featured in many of his works. He emphasized the spiritual meaning of the countryside, too. The styles that made an impact on his work included Fauvism, Futurism and Surrealism. Self-portraits and still lives were common in his repertoire, too.

Landscape, by Georges Kars, 1910

I knew the name Czech-French painter Georges Kars from a Prague exhibition of Czech artists in Paris between the wars. While initially taken with Impressionism, Cubism and Fauvism, he found his own path with dynamic and vibrant compositions. He made a lot of women’s portraits, self-portraits, nudes and half-nudes in his figural works. Sometimes he rendered still lifes and landscapes. Kars utilized the neoclassicist style for his portraits, nudes and still lifes. His paintings were world-renowned, displayed throughout Europe, the USA and Japan.

During World War I he served for the Austro-Hungarian army and even was captured by the Russians. He survived the experience and continued painting after the war.

A Walk in a Park in Florence, by Bohumil Kubišta, 1907

Of Jewish origin, Kars escaped France during 1942 and settled in Switzerland. However, he was so traumatized by the persecution of the Jews that he took his own life, jumping to his death from the fifth floor of the Geneva Hotel. During 1949 he was buried with his family in Prague’s New Jewish Cemetery.

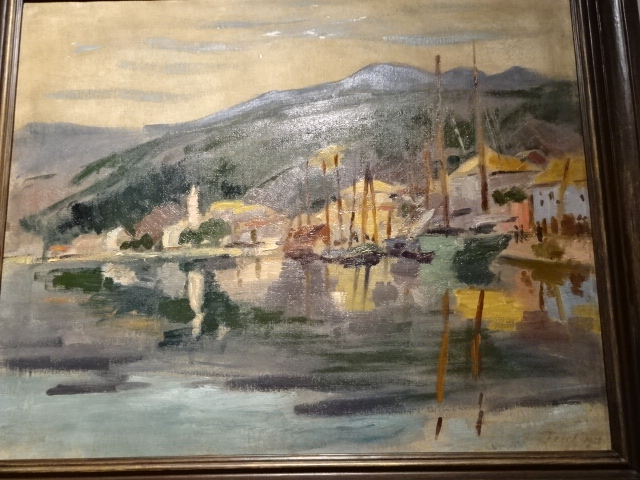

Brindisi, by Otakar Kubín, 1906

Another artist who was well-known while residing in Paris between the wars, Otakar Kubín, who also went by the name Othon Coubin, worked as a painter, sculptor and graphic artist, mostly living in France. Holding citizenship from France and Czechoslovakia, he made a name for himself rendering landscapes, mostly of Provence but also of Moravia. I loved his landscapes of Provence in the exhibition of Czech artists between the wars. These paintings were perhaps the highlight of his career.

While living in France during World War I, Kubín and his wife were interred in a camp imprisoning foreigners in Bordeaux. However, they were not held for long. In the 1920s, he held exhibitions in Paris with Pablo Picasso and Henri Matisse. Kubin was impressed with the Expressionism of Vincent Van Gogh. His depictions with figural motifs often were influenced by the death of his wife and son. His works were also seen in Japan, Switzerland and the USA. Some of his praiseworthy portrayals include a portrait of Kubišta, House in the Countryside, Cemetery Chapel in Boskovice, Imaginary Likeness of Edgar Alan Poe, Moravian Landscape and Auvergne Landscape.

The Metamorphosis, by Otto Coester, 1920

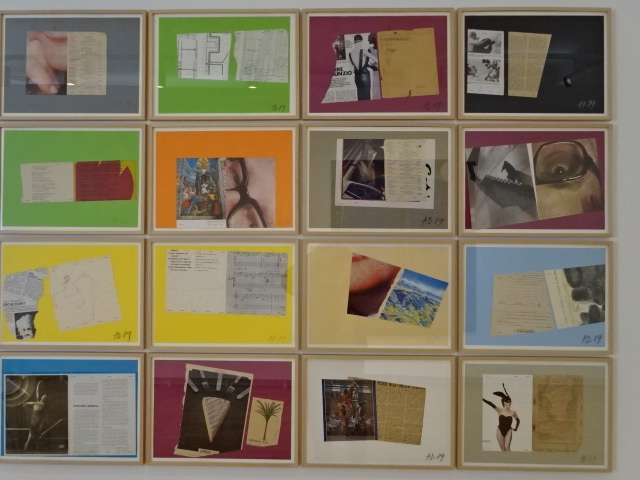

One of Kafka’s small black-and-white drawings as a young child was on display, and art promoting his various books also had a prominent place in the exhibition. Artistic renditions of The Metamorphosis were represented, for instance. German art and literature at this time also played prominent roles in society. An antisemitic attitude was seeping into some of the publications. The exhibition did not only concentrate on works in Prague but also art that had immersed itself into European society as well, providing a European context for these powerful renditions.

The Metamorphosis, by Wilhelm Wessel, 1924.

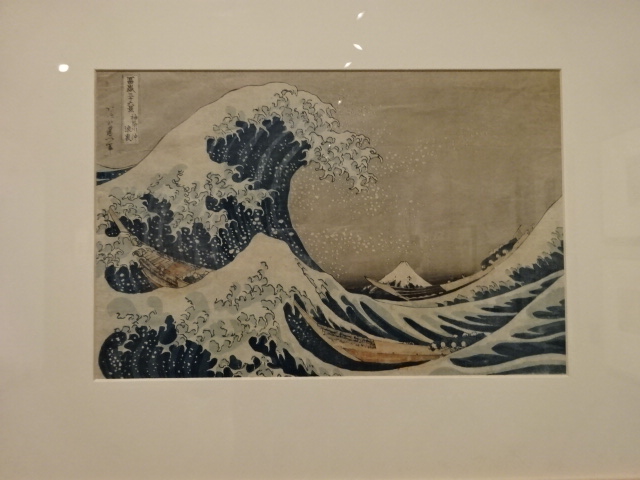

This exhibition took up my favorite Czech era of art – the end of the 19th and beginning of the 20th century. The Art Nouveau and symbolic nature of the works greatly impressed me as did emphasis on color in many paintings. I loved the expressionistic qualities of Munch’s artistic creations. Several paintings were by Japanese artists, and I saw a direct connection between the Czech Art Nouveau and the Japanese style. I could see the influence of Cubism in some paintings with many geometrical traits. I loved the Art Nouveau posters advertising exhibitions. The multifaceted visual experience of a person living in Prague during that era reminded me of the mixture of languages that had permeated culture and society.

The exhibition was thrilling as I thought back to that age and the various cultures people were experiencing. I felt that time period come alive through the artistic creations. Some of my favorite artists were represented, such as Bílek and Kubišta.

A Wave at Kanagawy, by Hokusai Kacušika, 1831

I also was enamored by the building in which the West Bohemian Gallery was housed. It had been used as a market place during the Middle Ages and boasted of a unique architectural style. I longed to learn even more about the end of the 19th and early 20th century as I left the exhibition and made my way to my favorite restaurant in Pilsen, U Salzmannů.

Tracy A. Burns is a writer, proofreader and editor in Prague.

Restaurant U Salzmannů, Pilsen