I had taken this train many times before, usually to Turnov, which was one stop further than today’s destination – Mnichovo Hradiště. The last time I had taken this route, the train had been furnished with new, comfortable seats, though the exterior had appeared dilapidated. This time, the seats were the usual ugly, red, vinyl kind divided into compartments that looked dirty. After riding the pleasant Viamont train to Bečov nad Teplou, I guess I had become a bit spoiled concerning train travel.

The trip took about an hour and 45 minutes, and it took another 15 minutes to walk through the pleasant town to get to the chateau. I remembered the chateau’s exterior from my visit here about 10 years ago, but it looked as if the walls had seen a few fresh coats of paint since my first time here. There were three parts to the tour – the Empire style theatre for about 50 or 60 spectators, the interior rooms with mostly 18th century furnishings and the lapidarium where 25 statues were kept in the church and chapel of a former convent.

The guide and I started with the tour of the theatre. On the way there, we stopped in a hallway where I saw large portraits and Baroque bureaus. A huge painting traced the genealogy of the Waldstein family, the clan who had owned the chateau for generations. I picked out Vilém Slavata from Chlum and Košumberk in a long, red robe and big, red cap in one portrait. I had visited enough chateaus to know that this nobleman and writer had been thrown out a window of Prague Castle during one of Prague’s defenestrations. Thankfully, he had fallen on a heap of manure. Passing the Hunting Hallway, I glanced at black-and- white graphics of various animals and noticed a depiction of a deer with one antler. Then we came to a machine that made the sound of wind. By turning a lever, the round, wooden contraption with a white sheet over it moved to produce the sound.

Then we entered the Empire style theatre. I took a seat on a bench that resembled the original seating. While the theatre was first mentioned in archival documents during 1798, it was renovated and given an Empire style appearance in the early 1800s on the occasion of the Holy Alliance negotiations, when Austrian Emperor Franz I, Russian Tsar Nicholas I and Prussian Crown Prince Frederick William discussed how to handle the revolts taking place throughout their lands, during 1833. The first play performed here was Carlo Osvaldo Goldoni’s The Servant of Two Masters, performed in German and Czech by actors who came from Prague. Three theatre groups from Prague’s Theatre of the Estates gave performances here for three nights. In the second half of the 19th century, the theatre fell into disrepair and was used as a furniture warehouse. It was not open for the public until 1999. The curtain was restored in 2001.

Then we entered the Empire style theatre. I took a seat on a bench that resembled the original seating. While the theatre was first mentioned in archival documents during 1798, it was renovated and given an Empire style appearance in the early 1800s on the occasion of the Holy Alliance negotiations, when Austrian Emperor Franz I, Russian Tsar Nicholas I and Prussian Crown Prince Frederick William discussed how to handle the revolts taking place throughout their lands, during 1833. The first play performed here was Carlo Osvaldo Goldoni’s The Servant of Two Masters, performed in German and Czech by actors who came from Prague. Three theatre groups from Prague’s Theatre of the Estates gave performances here for three nights. In the second half of the 19th century, the theatre fell into disrepair and was used as a furniture warehouse. It was not open for the public until 1999. The curtain was restored in 2001.

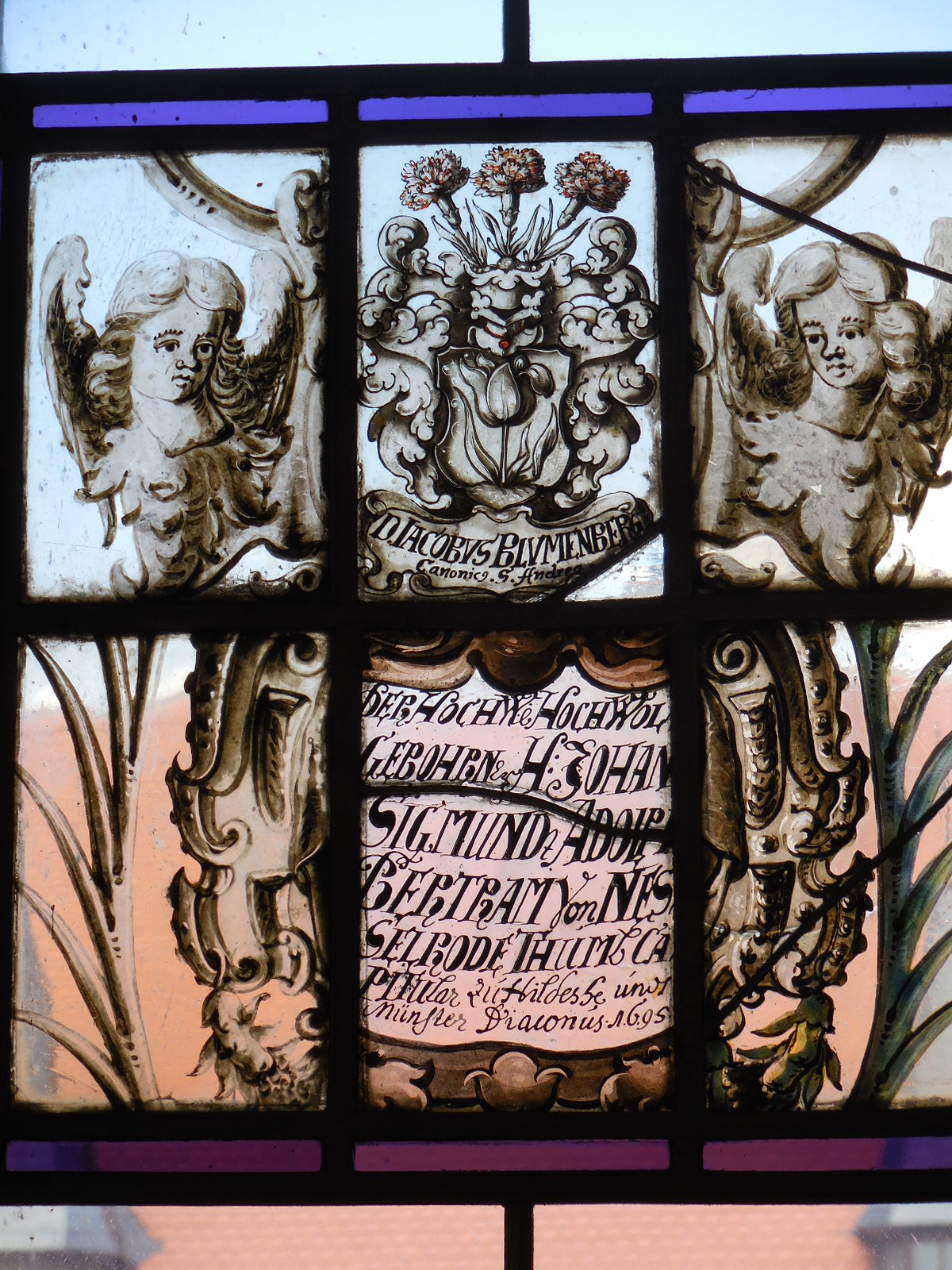

I was enthralled by the romantic landscape backdrop that was currently on display. It gave me a soothing, calm feeling. Some of the 11 plain, flat backdrops that the theatre possessed included a street view, a castle, a hall with columns and Prague Castle with the Lesser Quarter and Charles Bridge. The stage was 32 feet wide, 28 and a half feet deep and four feet high while the proscenium opening was 22 feet wide and 13 and three-fourths feet high. The theatre had one curtain and 54 wings, which were set at an angle to the stage instead of being placed parallel to it, as was the usual custom. The theatre did not use a mechanized wing system or wing trolley, either, but rather employed a groove system that utilizes upper and lower grooves to assure that the wings will stay upright. Also, the wings in this theatre were double-sided and therefore could be reversed easily. On the back wall behind the balcony a large genealogy painting of the Waldstein family, complete with cherubs, caught my attention. It celebrated the family’s pride of its heritage. The theatre is still on occasions used today.

The chateau had an intriguing history. It was built in the 17th century, during Renaissance times. The owner Václav Budovce of Budov joined forces with other nobles in a revolt against the emperor and was executed on Old Town Square in Prague during June of 1621. In 1623 the chateau was confiscated and subsequently bought by Albrecht Eusebius of Waldstein. In 1675 Arnošt Josef of Waldstein purchased it and kept it until the middle of the 20th century. The chateau was given a Baroque appearance in the early 1700s, although some rooms were given a Rococo makeover around 1750.

In a hallway full of portraits, I spotted the pointed beard of Albrecht of Waldstein, the one who had bought the chateau in 1623. A large painting explained the genealogy of Emanuel Arnošt of Waldstein. The guide said that when the researcher could not find all the ancestors of the Waldsteins, he made them up. The large, grey, puffy wig that Maximilian of Waldstein was wearing caught my attention, too. I also noticed that Count Vincenc had only one eye open. There was also a room to the side, roped off. Leaning over the rope, I glimpsed a tiny chapel with a Baroque altar of Saint John of Nepomuk and a Madonna with child. The altar was flanked by black Corinthian columns with golden tops.

Next came the Countess’ Antechamber. Someone had installed a 20th century telephone and placed it on a Baroque bureau, a sight which vividly contrasted the two eras, so far apart in technology and time. A still life painting adorned one wall, and a laundry basket with an exquisite floral pattern and muted yellow background sat on the floor. The stunning green, blue and brown chandelier symbolized the four seasons. I noticed that grapes stood for fall.

The oldest painting in the chateau, showing an old lecherous man and a young woman whom I suppose was very naive, hung on a wall of the Countess’ Bedroom. I noticed how both figures had baby pink skin. Why a countess would want such a painting in her bedroom is beyond me. In the visitors’ book, a thick, red book on an ancient desk, I could read the names of nobility such as Schwarzenberg and Lobkowicz.

The Italian Salon enthralled me with its stunning mural spanning three walls. The painter had never visited the Italian town presented; rather, he had painted it from an etching. From the embankment of the town pictured, one could see Naples and Venice in the distance. Two men and a woman were talking in one section, nobles had gathered in another, and in yet another part two men manned the oars of a small boat.

The Italian Salon enthralled me with its stunning mural spanning three walls. The painter had never visited the Italian town presented; rather, he had painted it from an etching. From the embankment of the town pictured, one could see Naples and Venice in the distance. Two men and a woman were talking in one section, nobles had gathered in another, and in yet another part two men manned the oars of a small boat.

The Study, which later became known as the Music Salon, featured a piano with the white and black keys reversed. I had never seen a piano with this unique trait. The Baroque white tile fireplace was decorated with two sea monsters that were supposed to be dolphins, as they slivered through the water with their heads pointed down. Small portraits also adorned the Music Salon. One showed Habsburg Empress Maria Theresa dressed in black, mourning the death of her husband.

The small picture gallery was roped off, which disappointed me. I wanted to study each painting in minute detail, but only was afforded a side view of the three walls totally covered in art. I noticed a woman reading while holding a skull and other paintings boasting hunting themes.

Next came the Hunting Salon. The three walls were covered in a mural painted in shades of dark green and featuring a forest, dogs and hunters. I noticed that a backgammon game consisted of pieces with faces carved on them. The ceiling fresco was devoted to Diana, goddess of the hunt. She held an arrow; one of her plump breasts was bare. The room also boasted a secret door.

The biggest room in the chateau was the Dancing Salon or Reception Salon, Rococo in style. A mirror sat flat on a round table that looked like a three-tier table for cakes wheeled around in luxurious restaurants. Porcelain figures decorated the three tiers while murals decorated two walls. I spotted this very chateau in the background of one part of the mural. Men clad in red with dogs were seen in a forest as a woman stood in the doorway, something having caught her sudden attention.

The Ladies Salon featured murals on four walls. They showed a countess posing in different professions. She was portrayed as a dancer, a flower-seller, a hunter, a fisherwoman and a traveler, among others. In the depiction of the countess as a flower-seller, I took note of the English park in the background and the flowers that decorated her hat. I was enamored by the backs of the chairs on which landscapes had been painted. The floral cushions were exquisite as well.

The most beautiful room in the chateau, in my opinion, was the Delft Dining Room that is immersed in blue-and-white Delft Faience porcelain from the 17th to 19th century, all original and handmade. I noticed some geometrically shaped vases and admired the wooden compartment ceiling, too. The Waldstein gold with blue coat-of-arms decorated the center of the Renaissance ceiling. I noticed some plates on a wall featuring windmills while a tray depicted a park with a fountain and statue.

The most beautiful room in the chateau, in my opinion, was the Delft Dining Room that is immersed in blue-and-white Delft Faience porcelain from the 17th to 19th century, all original and handmade. I noticed some geometrically shaped vases and admired the wooden compartment ceiling, too. The Waldstein gold with blue coat-of-arms decorated the center of the Renaissance ceiling. I noticed some plates on a wall featuring windmills while a tray depicted a park with a fountain and statue.

The Oriental Salon was full of Japanese and Chinese porcelain. I admired the orange and blue swirls of one Chinese plate hanging on a wall. The table and chairs were made of bamboo. Four vases represented the four seasons. A Japanese painted partition also adorned the room.

The table in the Meissen Dining Room was set for breakfast with its blue-and-white porcelain taking center stage. Yet what astounded me about Meissen craftsmanship were the chandeliers. Hailing from the beginning of the 19th century, this particular chandelier featured floral decoration colored green, pink, yellow and orange.

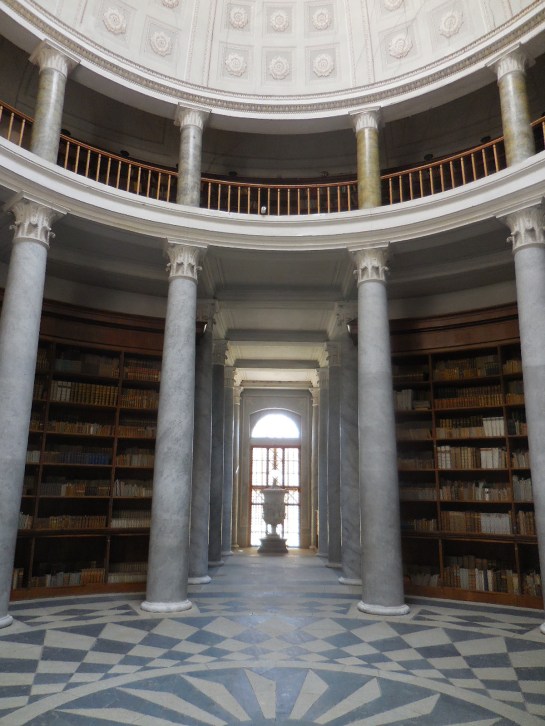

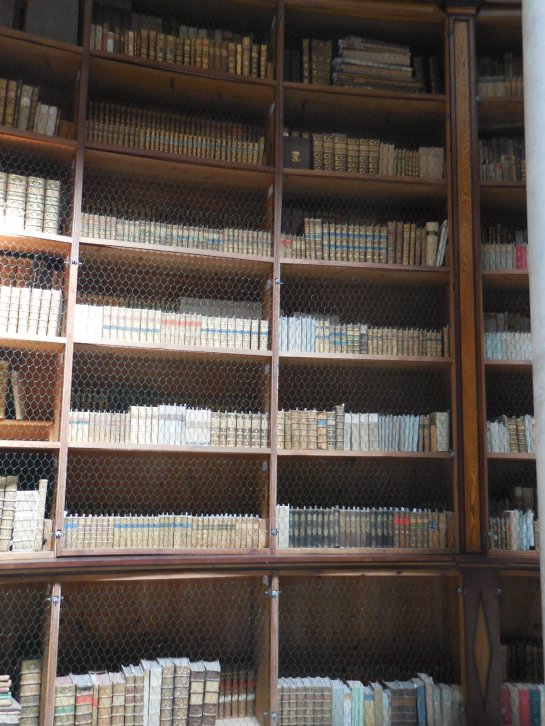

Although the library was composed of three rooms, a gate with bars prevented visitors from entering. This was the library where Giacomo Casanova had served as librarian during the 18th century, the guide reminded our group. His letters and manuscripts made up a significant part of the chateau archives, as did material from the Thirty Years’ War. I wished I could see more of the 22,000 volumes inside the gate as the shelves were decked with fiction as well as specialized literature, such as legal and historical works. Many books focused on alchemy, too. They were written in a variety of languages, including German, Latin, Czech, Italian and Hebrew. Two big globes stood in the foreground while a smaller globe and telescope could be seen in the background of the closest room.

Walking through a hallway before descending the stairs, I spotted a large portrait of an armor-clad Albrecht of Waldstein on a gray, spotted horse. Then it was time to visit the lapidarium.

The church and chapel of the former Capuchin convent appeared to be plain, nondescript. The exterior was even dilapidated. What was inside, though, proved absolutely stunning and breathtaking. As we first entered the Church of the Three Kings that joined the Chapel of Saint Anne, I saw about six small statues in a dark, small space. This will be disappointing, I remember thinking to myself. Then we turned the corner, and the room came alive with 25 statues of Baroque, Rococo and Empire style twisting and turning, dynamic and vibrant, most made of sandstone.

Home to these statues since 1966, the lapidarium featured monuments that had been deteriorating in the outdoors. Our group stood in front of the headstone of Alburtus de Waldstein, the name engraved prominently on one wall in what looked like marble. Then I walked through the room, my head spinning from all the dynamic and expressive movement flowing from the statues. I inspected the altar of the Saint Anne Chapel and noticed that Saint Anne had a child on her lap as they were reading, cherubs fluttering above. Next to them a figure seemed to be holding a painting.

Then I took in the statues. In a sandstone work hailing from the third quarter of the 18th century, the Virgin Mary had her hands clasped to her breast. A Saint John of Nepomuk portrayal by Josef Jelínek the Elder, dating from the second quarter of the 18th century and made of polychrome wood, featured that saint as a sort of visionary, peering into the distance, determined and confident. I noticed the dynamic folds in his white drapery. It looked as if they were fluttering in the wind. Another statue, named the Angel with the Attribute of Christ’s Suffering, had been erected in the early 1720s out of sandstone. I was stunned by the angel’s huge wings as the angel seemed to be moving toward the viewer, about to trample him or her. I also noticed the angel’s crushed nose and wished the statues were in better condition. If I was a millionaire, I would donate money to preserving Czech chateaus and castles, so that fascinating statues such as these could be restored.

Then I took in the statues. In a sandstone work hailing from the third quarter of the 18th century, the Virgin Mary had her hands clasped to her breast. A Saint John of Nepomuk portrayal by Josef Jelínek the Elder, dating from the second quarter of the 18th century and made of polychrome wood, featured that saint as a sort of visionary, peering into the distance, determined and confident. I noticed the dynamic folds in his white drapery. It looked as if they were fluttering in the wind. Another statue, named the Angel with the Attribute of Christ’s Suffering, had been erected in the early 1720s out of sandstone. I was stunned by the angel’s huge wings as the angel seemed to be moving toward the viewer, about to trample him or her. I also noticed the angel’s crushed nose and wished the statues were in better condition. If I was a millionaire, I would donate money to preserving Czech chateaus and castles, so that fascinating statues such as these could be restored.

The Lion and Putto, by master Ignatius Francis Platzer, was made of sandstone and hailed from the 1750s or 1760s. Putto, clutching a shield, was riding on an enormous lion. Perhaps the best known statue in the collection was Matthias Bernard Braun’s Perseus, a sandstone work from the early 1730s. Perseus appeared calm, not at all tormented, and I took note of his fluttering drapery and twisting body. Then I walked over to Saint John of Nepomuk with Two Angels by Karle Josef Hiernle, a sandstone piece from 1727. John of Nepomuk was flanked by two angels. One angel lightly touched the sleeve of John of Nepomuk’s garment. An angel held a finger to his lips, while the other pointed toward Heaven. Cupid heads decorated the bottom of the sculpture. John of Nepomuk ‘s head was leaning to the right, his hands were clasped and his eyes closed as if he were meditating.

After thoroughly enjoying my inspection of the statues, I went to lunch, where I ate my favorite chicken with peaches and cheese. Soon afterwards, I took a bus from the main square directly to Prague. Once again, I was fascinated by everything that I had seen in the chateau, and I needed time to process all the information and all the beauty that had surrounded me.

Tracy A. Burns is a writer, proofreader and editor in Prague.