Part I

I waited and waited. The tram going to the Dejvická Metro station was late. I kept glancing at my watch. If it did not come soon, I would miss the 6:40 a.m. Saturday bus to Karlovy Vary. I had been looking forward to seeing the castle and chateau in Bečov nad Teplou again for some time. I had planned this trip so carefully. Where was the tram? There were always trams coming in the direction of the metro station. Why did I have to wait so long? Had there been an accident? Was there a problem with the tracks? My heart was racing. Where was the tram?

Some nerve-racking minutes later, the tram did come, and I made it the Student Agency bus just as the doors were about to close. During the two-hour trip to the famous Czech spa town, I fretted about whether or not I would make the train to Bečov nad Teplou. I only had 15 minutes to change, which should be enough if the bus was on time. Still, after the incident with the tram, I was worried….

It turned out that the bus dropped passengers off at the Karlovy Vary train and bus station at 8:30 a.m. rather than its 8:45 designated time. I had an entire half hour before the train departed. First, I waited in line at the only window for train tickets. There was a line of potential passengers, but no one appeared to be manning the window. After waiting an excruciatingly long 15 minutes, someone did come.

The train was already on platform three. When I saw the Viamont train, I was surprised. It was new, clean and comfortable, not like those old red trains with uncomfortable seats that I had often taken to small towns for so many years. The stops were even announced and displayed electronically on a sign above the seats. I did not have to worry about getting off at the wrong stop – not this time anyway.

The train ride was scenic and relaxing. We traveled through woods and also past a golf course with ponds and a stream. I could see the Bečov nad Teplou chateau and castle on a high rock from the train stop in the valley. From there it was about a 15-minute walk through the small town with some narrow, steep side streets and a church on a hill. Passing a half-timbered house that seemed to belong in another century, I came to the picturesque square with its pensions, restaurants offering outdoor seating, antique store and souvenir shop.

On my way I noticed many Baroque or Classicist houses, which were in need of repair.

From the square I gazed at the pink Late Baroque chateau and headed directly to the box office. It was only 9:45 a.m. The chateau and castle opened at 10:00 a.m. Yet there was already a line of at least 10 people ahead of me, mostly seniors.

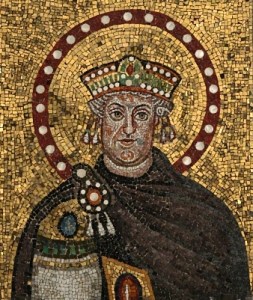

In the end there were about 20 people ready for the 10:00 a.m. tour, so they were split into two groups. One group started with the historic interiors, and the other group – my group – began with the Romanesque reliquary of St. Maurus, where fragments from the bodies of three saints – St. Maurus, St. John the Baptist, and St. Timothy– were kept. I had never been on this tour because the reliquary had opened to the public in May of 2002, and my first visit took place during March of that same year.

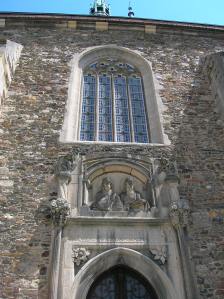

First, I crossed a small bridge decorated with the statues of John Nepomuk and the Jesuitical clergyman Jan de Gotto, both of which dated from 1753. I reached the front gate, framed in a 16th century Renaissance portal. Before going upstairs to the rooms dealing with the holy relic, we stood in a hallway decorated with portraits of soldiers riding horses off to battle. I noticed the plume on a soldier’s helmet and the castle in the lower left-hand side background of that portrait. The castle seemed so small and powerless against the mammoth soldier seated on a horse that seemed almost to bolt out of the canvas. I also was impressed by the elaborate saddle that the artist had rendered.

On the floor above the hallway, a display case in the first room dealing with the unique treasure featured a small Christ figure, a marquetry cross that appeared to be inlaid with gems and scapulars of the Beaufort-Spontin family. It also contained pictures of relics found in the richly decorated tomb box, such as small textile bags, bits of paper and small stones.

A map covered another wall. The guide pointed to Belgium and explained that the reliquary hailed from a Benedictine abbey in that state, from a city called Florennes. The reliquary dated from 1225 to 1230 and contained the remains of the three saints mentioned above; yet more recent DNA tests proved that there were the remains of five people in the chest, two of whom are men from the third century AD, according to the guide. He also explained that these sorts of shrines were important in society because people believed that they were the source of health-related miracles. He added that Saint Maurus was a sort of mystery man for scholars; it is only known that he was a saint and martyr in the first or third century AD, nothing more.

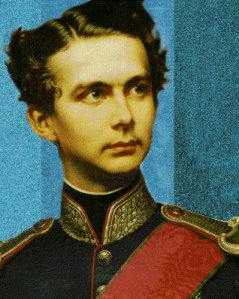

After surviving the French Revolution, the unique object was kept at St. Gengulf’s Church in Florennes. When Alfréd de Beaufort bought the reliquary in 1838 from a Belgian church council for 2,500 francs, it was in a decrepit state. He brought it to Bečov and had it repaired from 1847 to 1851. When his grandson had to flee in 1945 after the second world war because he had cooperated with the Nazis, he hid the reliquary in a backfill of a chapel in the castle here.

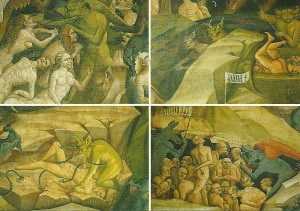

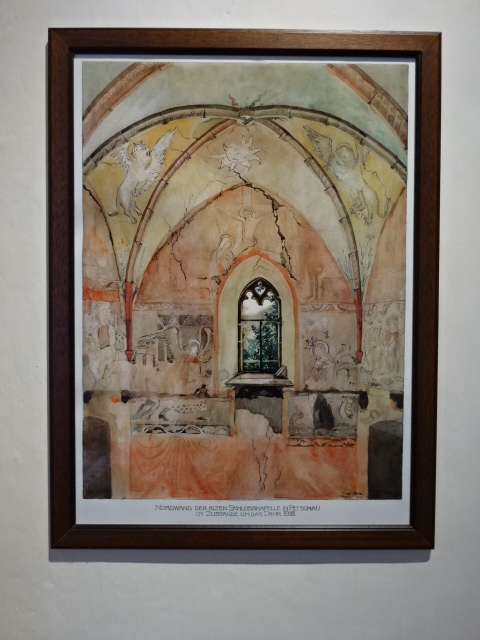

In the next room there was a reproduction of a partial mural from the castle chapel, which, along with the rest of the castle, was not open to the public. (Visitors were, however, allowed inside the chateau’s chapel.) The guide elaborated on the fascinating history of the treasure, which sounded like something out of a detective story.

The reliquary of Saint Maurus from http://www.svatymaur.cz

The reliquary had remained hidden for 40 years. In 1984 an American named Danny Douglas wanted to buy an unspecified treasure hidden in the Czech lands during World War II and was willing to pay 250,000 USD for it. This was a financial offer that the Czechoslovak government could not afford to pass up. But the Czechs had to figure out which artifact he intended to purchase. During further talks with Douglas, the Czechs were informed that the object was oblong, the size of a conference table, hollow, made of metal and buried about 100 kilometers from Nuremberg, among other facts. Finally, they narrowed it down to the reliquary, which had to be buried somewhere in this chateau and castle.

A black-and-white video dated November 5, 1985 showed criminologists unearthing the chest in the chapel. I could not help but notice how dilapidated the façade of the building was, how different it looked from today. Of course, the Czechs would not allow the treasure to leave the country. In the end, the contract with Douglas was not signed.

The next room dealt with the restoration process. In display cases I saw tools and utensils used to fix the reliquary, such as chasers, a metal chiseller and engravers. The guide also mentioned that the statues on the exterior of the reliquary were made of silver tin and took 11 years to restore. Imagine that! Eleven years! When the criminologists found the treasure, it was damaged. The metal pieces were corroded, and parts of the figures and reliefs were no longer attached to the relic. Due to issues relating to property rights, restoration did not begin until mid-1993.

The guide also explained why the treasure with its fragile, small gilded silver statues took such a long time to restore. Restorers had to make miniature, detailed parts for the statues, hands and arms for example. The restoration of the 12 apostles and reliefs on the roof proved the most challenging. The young man conducting the tour mentioned that the restorers had to drill about 3,000 holes for nails to keep the object from getting damaged. Don’t overlook the fact that the chest included filigree with pieces of glass, precious stones and gems.

Another display case featured the plaster casts for the circular reliefs on the chest, showing biblical scenes. In one Salome carried the head of St. John the Baptist. Another featured the dance of Salome. Plaster casts of saints were also displayed, including Saint Paul, Saint Jude Thaddeus and Saint Bartholomew. A large picture on one wall showed that the treasure was decorated with birds and mythological figures and inlaid with gems. No one knows how the gems were placed on the chest because not even a laser is capable of doing that kind of precise craftsmanship, and they certainly did not have microscopes back in Romanesque times.

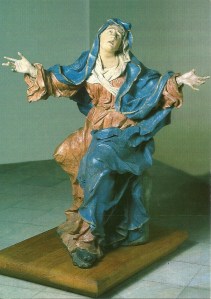

In the fourth room I looked at the original oak box that had been found inside the chest. The restorers had to create a new wooden core for the object. The display cases along the walls showed various reliquaries. In one case I saw two gem-studded rings. I also gazed at a number of golden Baroque monstrances, so elaborate that they almost made me dizzy.

Another closeup of the reliquary of Saint Maurus from http://www.svatymaur.cz

Then we finally came to the dark room containing the unique treasure. We only had five to seven minutes in the space. I noticed how Saint Maurus’ drapery seemed to flutter as he gripped a sword in one hand on the front of the chest. Christ was giving a blessing on the opposite side. On the roof were 12 large reliefs relating the life of Saint Maurus and of Saint John the Baptist. Small columns with floral decoration also decorated the chest. Apostles were shown with staffs; one gripped a cross. Saint John the Evangelist held a goblet. I noticed the precise curls in his hair as well as his flowing drapery. The detail in the saints’ facial expressions was also stunning.

Golden swirls and gems decorated the treasure as well. I noticed the precision of the inlaid gems and the precision with which the small hands of the apostles had to be made. My head was swimming. There was so much detailed decoration to take in at one time. I wanted to study the chest in small parts, truly appreciating the precision of the figures and reliefs. I knew I was staring at one of the most beautiful artifacts I would see in my life.

After a short time, we were ushered out of the dark room, and the first tour ended. In 10 minutes, it would be time for the tour of the interior rooms. I was enthralled by the first tour and excited about the second.

Part II

The tour of the historic interior rooms began, as did the last tour, in the hallway with the large wall paintings of soldiers on bolting horses. Then we went to a room displaying a model of the complex as it had looked in the 19th century, under the Beaufort family’s tenure. I admired the terraced gardens with pools and fountains. The guide pointed out the castle’s Chapel of the Visitation of the Blessed Virgin Mary in the tower, which was the oldest part of that building. (Only the chateau, not the castle, was open to the public.)

Donjon, taking its name from Early Gothic castles shaped like towers in southern France, had been a tower of four floors with toilets on every floor. The family had lived in this section of the castle. The Pluhovský Palace, still flaunting a Classicist style, was comprised of three houses. A watch-tower also had stood on the property, though it is only six meters high now, as it had been shortened and transformed into an observation terrace during the 19th century. The vibrant, pink Late Baroque chateau, built in the 18th century by the Kounic owners, was one dominating feature of the model.

The guide familiarized us with the history of the castle and chateau as I glanced occasionally at the portraits, maps and black-and-white landscapes on the walls. In the 14th century the village’s status was raised to that of a town. The castle remained the property of the Hrabišic of Osek clan until the beginning of the 15th century. From the 13th to the 16th centuries, the place prospered thanks to its gold, silver and tin mining. In fact, during the 16th century, Czech tin from the Bečov region was praised as the best in Europe. The manufacturing of pewter added to the town’s wealth.

But times changed as the Hussite army destroyed the castle during the Hussite wars that took place from 1419 to 1434 and pitted several factions of the armies of martyr Jan Hus’ followers against each other. The Holy Roman Empire, Hungary, The Pope and others joined forces with the moderate Hussites. The castle was also in decline after the Thirty Years’ War, and the town never again reached its former level of prosperity. During the 18th century the Kounic family bought the castle, adding the chateau and bridge.

Then in 1813 Fridrich Beaufort-Spontini took over as the owner, which was a turning point in the buildings’ history. The Beauforts made many improvements to the castle and chateau. It was Alfréd Beaufort who created a Baroque style park with six levels of terraces. He repaired the castle and chateau, set up the botanical gardens, constructed an open-air theatre and brought the reliquary of Saint Maurus to Bečov. Because his grandson Heinrich collaborated with the Nazis during World War II, the property was confiscated. Objects in the castle were plundered. Townspeople stole some artifacts while other pieces of art and crafts were sold to antique stores.

After that, various owners were in charge of the castle and chateau. The castle became a school for workers while Pluhovský Palace was supposed to, but never did, become a museum. Reconstruction of the property took place from 1969 to 1996, when visitors were finally allowed inside the Late Baroque chateau. Back then a West Bohemian Gothic Art exhibition was housed in the chateau. Now the original furniture has been put back in the building, though the spaces are organized differently than they had been in the 19th century, when the chateau’s rooms had served a representative function, while the family had been living in the castle.

On the ground floor we entered the library, where each bookcase was decorated with four columns and had a triangular slanting roof culminating in a point. Reliefs of a female reading adorned the bookcases, which shelved 3,000 books for representative purposes. The chateau had another 14,000 books stored elsewhere.

From there, we went up the staircase with the oak balustrade that originated in the 19th century to a landing decked with hunting trophies, rifles and swords intertwined as well as a tattered Austro-Hungarian army cap. I was impressed with the vibrancy of the pink hue in one room that sported a pink couch, pink chairs and a pink tablecloth under a glass table. The gold décor on the white tea cups also caught my attention. I could see the tower from the window.

But the most significant part of this room was its graphics’ collection, hailing from the 17th century Netherlands, including one by Sir Anthony van Dyck. There were also four portraits of properties – three chateaus and one castle – owned by the Beaufort family when they had Bečov. Graphics of mythological figures and floral still lifes were on display, too. I also noticed how the female figures in several portraits sat so stiffly and how delicately flowers were handpainted on one vase.

The Red Parlor was next. A blood red couch and four armchairs gave the space its name. One painting from the 17th century Netherlands sported a music theme. Another painting showed nobles in an Italian park. My eyes darted to the brown and white marble columns in the foreground. There were two mistakes in the painting, the guide explained. Firstly, the trees depicted could not grow there. Secondly, through the summerhouse window it would not be possible to see a forest but part of the port and sea rendered next to it. We also saw a toilet with a keyhole. Only the person who had the key could use it. Lower-class nobles would have cleaned it. I also glanced at a portrait of an elegant lady with ruddy cheeks.

The Tapestry Parlor featured two huge tapestries pictorially narrating the story of David and Goliath. They were made in Brussels from 1620 to 1630. The Baroque table was intriguing as well. Its legs seemed to be decorated in the shape of some strange sea animal. It turned out that the animal depicted was a dolphin, but the artist had never seen a real one so he had used his imagination. On a dresser stood a Baroque clock complete with a realistic-looking giraffe.

Another tapestry hung from the wall in the next room as did several Spanish paintings from the 16th and 17th centuries. In one a woman was crying over the death of the Spanish king and another woman was protecting a child.

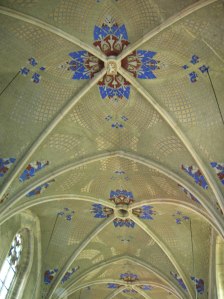

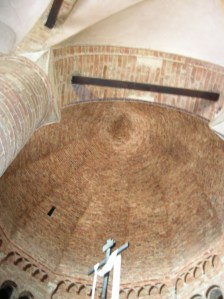

Last but certainly not least we made our way into the chateau’s chapel. At the entrance stood two gold statues of what appeared to be griffins holding candlesticks. Saint Peter Chapel was built in Neo-Romanesque style around 1870. The gilded altar was simple with a painting of Madonna and the Christ Child. Mary held one hand down with her palm up as she looked straight at the viewer, challenging his or her gaze. Both the Madonna and Jesus sported golden halos. On the walls were 14 Stations of the Cross painted in white enamel on copper plates. I noticed how Christ was lugging a heavy, plain cross in one depiction. In another he was sprawled over Mary’s lap, dead, a halo over his head. A white tiled stove stood behind a secret door. What attracted me most, though, was the ceiling. The blue with gold décor on the ceiling made the room dynamic, made it feel almost alive, imbuing it with a distinctive power.

The guide let us into the terraced garden, Baroque in style. From the edge of the garden I got an excellent view of the surroundings, with homes in the valley and a forest beyond. I thought to myself that these last two hours had been well-spent.

I made my way to an outdoor table at a pension’s restaurant in the picturesque square not far from the museum of toys, motorcycles and bicycles. I sat in the sun, facing the cheery, pink chateau façade for almost two hours, eating chicken, writing postcards and reading. Then I climbed the hill to the town’s church. I tried all three doors but found it locked. I had read in a brochure that the interior was in Rococo style. It was a pity that I could not see the interior.

Walking past the half-timbered, derelict-looking house on Railroad Street, I retraced my steps to the train station, where I waited for the new, clean train back to Karlovy Vary. After another scenic train ride, I made the next bus from Karlovy Vary to Prague with minutes to spare and spent a relaxing two hours thinking back on my exciting day.

Tracy A. Burns is a writer, proofreader and editor in Prague.

Visit in summer of 2025

I went back to Bečov in 2025 after the chateau and castle had undergone lengthy reconstruction. I only had time to see the reliquary. I did not have a chance to go on the tour of the interior rooms. The entrance rooms to the reliquary of Saint Maurus had changed considerably. Now visitors read panels on walls to get their information about the history of the reliquary. There was no enthusiastic guide to narrate the mystery about hidden treasure, and this was something I sorely missed. I recalled the guide’s exuberance that made the viewing of the reliquary all the more intriguing. Perhaps these panels, in English and Czech, were more visitor-friendly. They were certainly detailed and easy to understand. When in the main space, tourists get 15 minutes to walk around the reliquary and look at the other objects found with it. There is a display of beautiful relics in the entranceway leading to the room where the reliquary is located, too. Old photographs of the castle also make an appearance.

Some pictures of the entrance rooms before the space with the reliquary:

A detailed explaination of the parts of the reliquary and their significance

A display that appears as did the church floor when it was excavated for the treasure