David Caspar Friedrich, The Wanderer

As usual, this past year was punctuated by travel, though most trips only lasted one day or half of a day. Still, I was able to explore many sights within a two-hour distance of Prague. Once again, I realized that the Czech Republic blossoms with beauty in every niche of the country.

Perhaps the painting that best expresses my year of travel is one I saw at an exhibition of David Caspar Friedrich’s paintings from the Romanticist era. While admiring his “The Wanderer,” I saw the back of a male figure in the forefront, standing on a cliff as he peered at the mist-filled mountains beyond. It epitomizes why I love travelling: to discover new worlds, to muddle through that mist, reaching a clarity that allows me better to understand myself as well as to gain historical knowledge.

By David Caspar Friedrich, on display at Albertinum for temporary exhibition

In the Dresden Albertinum, I was mesmerized by Friedrich’s landscapes. Many featured vibrant colors and a brilliant use of light. He also created dark paintings with a chiaroscuro element that gave them a mystical appearance. Some of his landscapes included a solitary figure traveling alone in nature. Friedrich’s gnarled trees in barren environments were symbolic. I felt especially drawn to his portrayal of mountains in shades of pink.

By Marc Chagall, on display at Albertina in Vienna for temporary exhibition

By Paul Gauguin

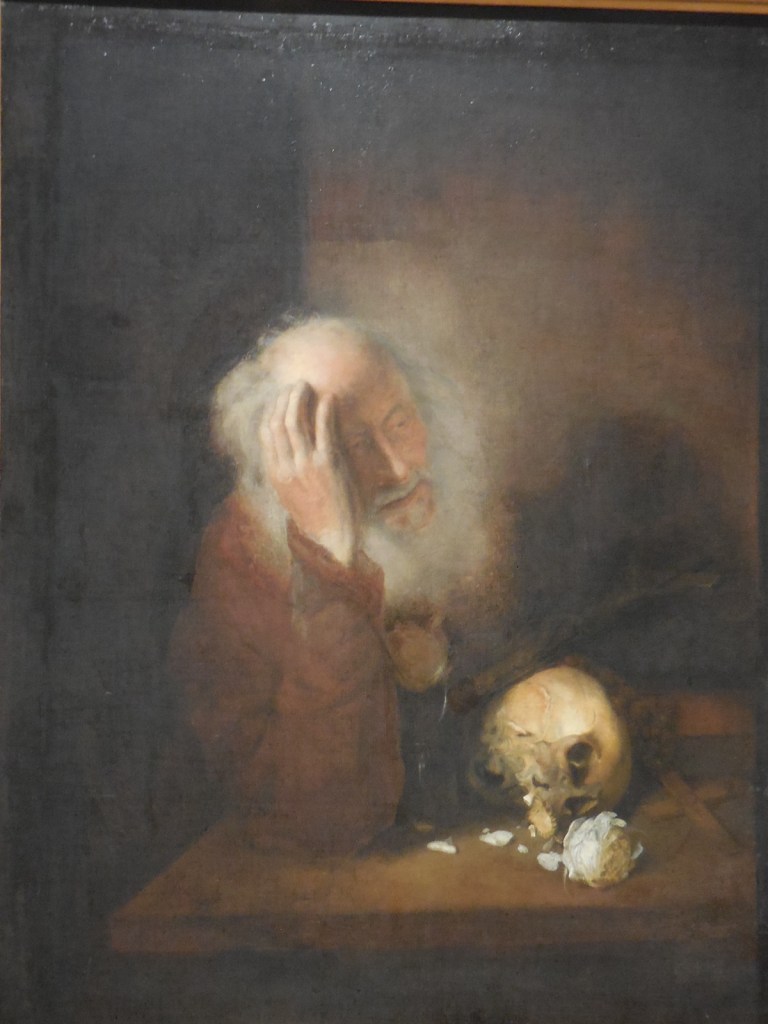

By Hoogstraten, Rembrandt’s pupil

I spent three days in Vienna going to major exhibitions featuring works by Chagall, Gauguin and Hoogstraten, a star pupil of Rembrandt. I hadn’t realized how many of Chagall’s paintings took on Jewish themes and serious topics. I had always thought of Chagall’s art as fun-loving and colorful. My favorites were those inspired by Paris and the circus, created in bright blues and yellows. The Gauguin retrospective showed his works from various time periods, so it was possible to see his specific artistic developments. I was most impressed with his early landscapes. I had not heard of Hoogstraten, whose portraits brought out the soul in the sitters just as Rembrandt’s did. His intriguing use of perspective in some paintings also impressed me. Works by Rembrandt also enchanted me in this exhibition.

Franz Xaver Messerschmidt, Character Heads

by Gustav Klimt on permanent display at Upper Belvedere

By Václav Špála, on display at Upper Belvedere

City of Vienna Museum, permanent collection

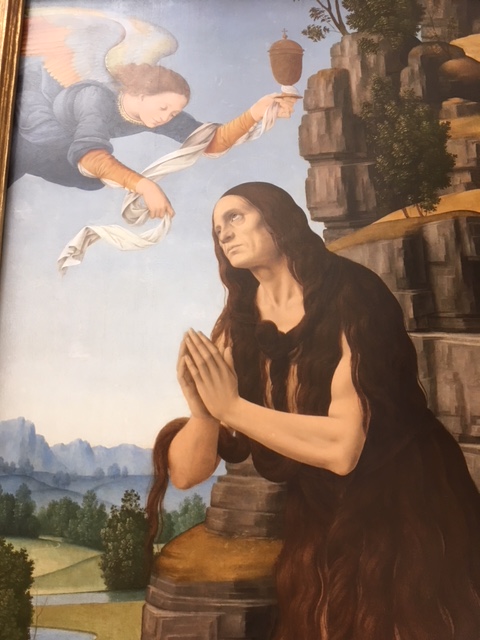

We also visited the Upper Belvedere Palace Museum in Vienna. While it is best known for its Gustav Klimt and Egon Schiele creations, I was entranced with the medieval art in the basement and the Central European collection that featured Czech greats such as Jan Procházka, Bohumil Kubišta and Václav Špála. The Klimt paintings were extremely powerful as were all the Impressionist and Post-Impressionist works. My favorite part of the museum involves the unique Late Baroque Character Heads by Franz Xaver Messerschmidt, who rendered alabaster busts of insane people with unique facial expressions. You could see into their souls. In Vienna I entered the City Museum for the first time. The exhibits trace the history of the city from the beginnings to modern day. I saw intriguing paintings, furnishings, posters and objects, among others.

by Eva Švankmajer

Puppets by Jan Švankmajer

Puppet by Jan Švankmajer

I also went to many exhibitions in the Czech Republic outside of Prague. In Kutná Hora I visited an exhibition of works celebrating the 90th birthday of Jan Švankmajer, a surreal artist, along with creations by his wife Eva. The exhibition Disegno Interno included collages, graphic art, objects, book illustrations, drawings, paintings, animated film creations and puppet theatre of both artists from the 1960s and later. Their creations included works that resemble Rudolfine Mannerist renditions as kinds of cabinet of curiosities and art inspired by Giuseppe Arcimboldo. I also noted the inspiration of the Baroque tradition in puppet theatre. Other works fell into the categories of art-brut, eroticism, fetishes and collages influenced by Max Ernst. Much of their art was deeply rooted in the writings of Edgar Allan Poet and Lewis Carrol. Scenography for Czech film was another section. I realized for the first time that surrealist art had been influenced to a great extent by Mannerist trends.

From Through Kafka’s Eyes, graphic art about The Metamorphosis

Through Kafka’s Eyes, Oto Kubín, Brindisi, 1906

In Pilsen I went to an exhibition called Through Kafka’s Eyes, featuring the art that had surrounded Kafka at the end of the 19th century and the beginning of 20th century. I saw posters for Czech art exhibitions in the early 20th century and those advertising 19th century Japanese art as well as works by stellar Czech artists. Paintings by Kubišta, colorful and vibrant, were represented along with sculpture by František Bílek. Czech artists who spent their interwar years in Paris were included, such as Oto Kubín and Georges Kars. Kafka’s own Jewish-themed drawings were a highlight. German art and literature rounded out the intriguing exhibition.

Great Synagogue, Pilsen

Great Synagogue, Pilsen

I also took the time to visit the Great Synagogue in Pilsen, the second largest synagogue in Europe and third largest in the world. On the onion-shaped dome the Star of David stood out. What I admired most was the vaulted ceiling punctuated with blue and gold adornment. Another feature that amazed me was the artistic mastery of the stained glass windows with geometric shapes and figures. The interior is furnished in Oriental style with Neo-Renaissance elements.

Pilsen, U Saltzmannů

We ate at my favorite restaurant in Pilsen, U Saltzmannů, the oldest pub in the city. The Czech food at this establishment cannot be surpassed. I had fried chicken steak this time.

Škoda Museum

In Mladá Boleslav, about 70 kilometers from Prague, I visited for the first time the Škoda Museum, named after the popular Czech automobile manufacturer. The company began making bicycles with Václav Klement and Václav Laurin at the helm in 1895 and soon developed a rich tradition of producing cars. The automobiles on display ranged from vehicles made at the end of the 19th century to those produced in the modern day. I liked the early bicycles, including a two-seater for postal carriers. The cars from the early 20th century were also favorites.

In that same city, we also visited the Aviation museum of Metoděj Vlach, which explored the history of aviation with more than 25 airplanes in the main hall, some hailing from World War I. I saw the 1913 G-III by Gaston and Réné Caudron. It had an open cockpit and 9-cylinder rotary engine. The two-seater wooden plane constructed by the Beneš company called a Be-60 Bestiola featured a 4-cylinder engine and had been flown from 1936 to 1940. The adorable W-01 Little Beetle had been used for airshows in the 1970s.

At that museum, I also learned about the career of pilot Alexander Hessman, who also had starred in a 1926 silent Czechoslovak film. He was the organizer of the Czechoslovak aircraft for the 1936 Olympics. After the Nazi Occupation in 1939, he helped pilots escape with false passports, and he wound up fleeing from the Protectorate to France and then to the USA in January of 1940. After World War II, he returned to Czechoslovakia but fled from the Communist regime, settling in the USA, where he was a technical assistant with PAN AM in New York City.

Mexican mask, Museum of Glass and Jewellery, Jablonec nad Nisou

I traveled several times to north Bohemia this past year. One time I went to Jablonec nad Nisou, where the Museum of Glass and Jewellery was located because of the rich local tradition in these fields. I was immersed in the exotic jewellery of strung and woven glass seed beads by North American Indians, using products from north Bohemia. A mask of the jaguar hailed from the Huichol Indian tribe in Mexico. Glass seed beads from Jablonec nad Nisou were used to make a necklace by the South African Zulu tribe, dated from 1880 to 1900. Jablonec has been the location of the mint for the country’s currency, so many commemorative coins were on display.

I also was impressed by buttons made of glass, metal jewellery and black glass jewellery as well as wooden and plastic jewellery. Colorful handbags, masterfully designed, also made up the collection. The Waldes Museum of Buttons and Pins included more than 5,00 buttons, clasps and buckles with the oldest dating from 9 BC. The Bohemian glass exhibition showed off glass in many styles ranging from medieval and Renaissance to Empire and Biedermeier to Art Nouveau and Art Deco to modernism and contemporary. The museum also has the largest public collection of glass Christmas ornaments in the world with more than 15,000 objects. I saw ornaments of angels, birds, cats, dogs, Santa Clauses, gingerbread men and much more, all contemporary.

Josef Lada’s Villa in Hrusice

I made my first visit to Josef Lada’s Villa in Hrusice, where that author, painter, book illustrator and scenographer had lived while making some 600 paintings and 15, 000 illustrations. I saw his paintings of idyllic village life featuring all four seasons. Children threw snowballs and make snowmen in a quaint village in one painting while a squirrel was perched attentively on a tree branch, overseeing a tranquil village scene in another. Pub scenes showed humorous drunken brawls. I would have loved to have owned one of the charming cottages depicted in his paintings. I loved the paintings of knights and dragons from fairy tales as well as the paintings representing the months of the year. His paintings of scenes from Jaroslav Hašek’s antimilitaristic, multi-volume classic about the Good Soldier Švejk in the First World War caught my attention. Many of his paintings focused on holiday traditions. I also saw his humorous drawings and caricatures.

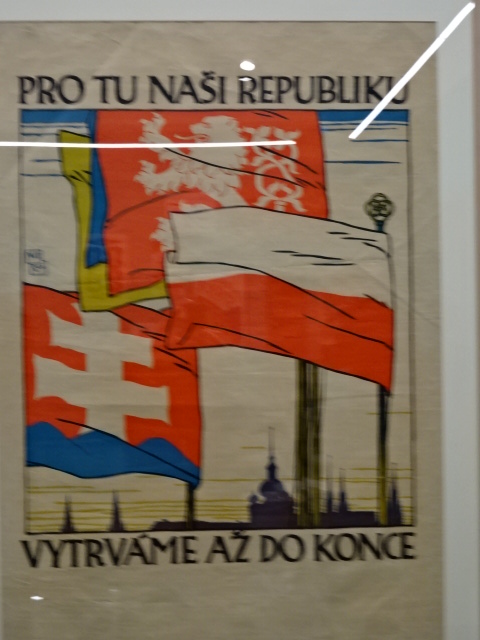

From the First Republic of Czechoslovakia

Poster by Václav Ševčík commemorating the day of the invasion by the Warsaw Pact armies, August 21, 1968

In Prague I took advantage of the stunning exhibitions this past year. I went to two excellent shows at Kampa Museum. One featured Czech graphic art from the founding of Czechoslovakia in 1918 to the present. I saw the first star-studded designs for the Czechoslovak flag as well as many political posters from the World War II era through Communist times to the Velvet Revolution of 1989. Václav Ševčík made a poster focusing on the day of invasion of the Warsaw Pact armies into Czechoslovakia on August 21, 1968, when the country’s liberal reforms were squashed. The poster shows a blood-red tear below an eye outlined in black on a white background.

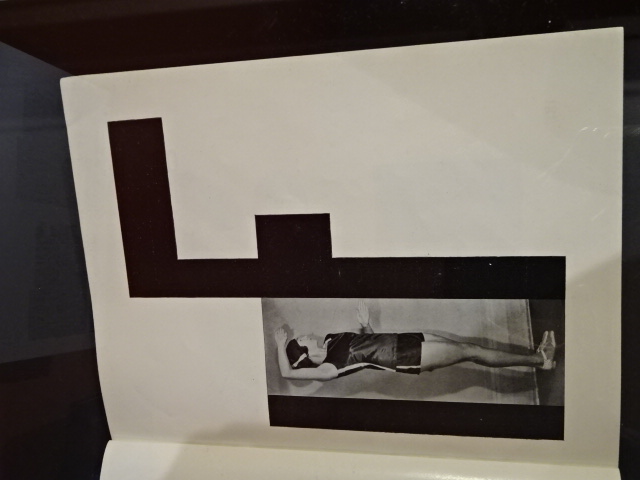

Vítězslav Nezval, Alphabet, with typography by Karel Teige

Kampa Museum, Identity exhibition of graphic art, Cindy Kutíková

Other sections concentrated on magazine and book design. I saw beautiful children’s volumes illustrated by Lada, Josef Čapek and Jiří Trnka. I was drawn to the covers and typography of Karel Teige, an avantgarde interwar artist. The exhibition showcased contemporary times by displaying a colorful, large Quantum Beaded Sweater created in 2020 and 2021 by Cindy Kutíková, for instance.

Václav Tíkal, 1944

Otakar Nejedlý, Waterfall, 1913-14

Another exhibition at Kampa Museum focused on paintings from the private collection of entrepreneur Vladimír Železný, purchased for his Golden Goose Gallery. Called The Goose on Kampa, the show featured 70 paintings representing works from the beginning of the 20th century through the 1960s, such as creations by Toyen, Jiří Štyrský, Špála, Emil Filla, Jan Zrzavý and Mikuláš Medek. One painting that caught my undivided attention was Václav Tíkal’s 1944. A hand partially covered in a ripped black glove showing the fingertips, thumb and part of the palm was emerging out of the frozen, snow-covered earth in a barren landscape.

Otto Gutfreund, Viki, 1912-13 from Cubist period

On that day I also explored the Kampa Museum’s permanent collection, specifically the sculptures of Otto Gutfreund, whose early works can be classified as Cubist. His later creations, made after World War I, featured traits of Civilism, which promoted themes of everyday life.

Bohumil Hrabal, 1952, Tragedy! What a Tragedy!

At the Museum of Czech Literature, I greatly appreciated a small exhibition due to my interest in the works of the late 20th century Czech fiction writer Bohumil Hrabal. The modest show emphasized the artistic relationship and friendship of Hrabal and abstract artist Vladimír Boudník, who created the “Explosionism” style. I was most impressed by Hrabal’s collages from the 1950s. One featured a Singer sewing machine, a naked baby and barbed wire heading into the horizon as white crosses in a graveyard punctuated the picture. It was called “Tragedy, What a Tragedy!”

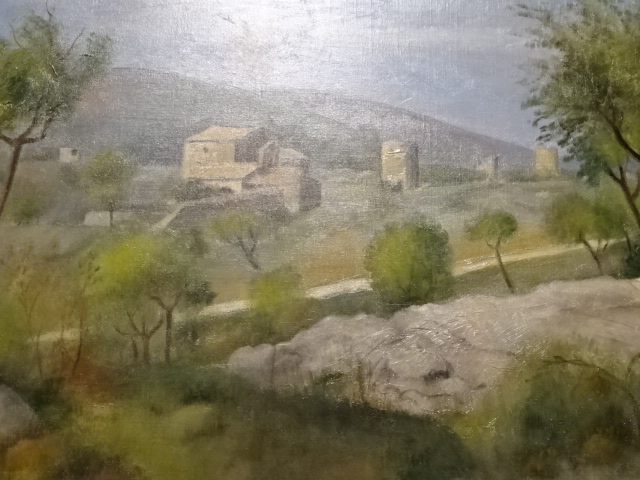

Oto Kubín, Chapel in Simione, 1926

Maurice Utrillo, Chateau de la Seigliere (Aubusson), 1930

The Wallenstein Riding Stables was the site of an intriguing exhibition about artists from Bohemia residing in Paris between the wars. They were part of the “Paris School,” which featured a variety of styles. Czechs Kars, Kubín (Othon Coubine) and Francois Zdeněk Eberl made strong impressions in the lively, vibrant Paris of the 1920s. The themes of the paintings were many: portraits, cityscapes, street life scenes, café and entertainment scenes as well as a focus on the circus and cabaret. I was drawn to Kubín’s landscapes of Provence. The lavender fields were my favorite. Also represented were foreign artists, including Marc Chagall and Maurice Utrillo.

Hendrick Goltzius, The Four Disgracers, 1588

Also at the Wallenstein Riding Stables, the exhibition “From Michelangelo to Callot: The Art of Mannerist Printmaking showed off more than 200 works of 16th and 17th century graphic art, drawings, paintings, jewelry, etchings, lithographs, ceramics and other artistic crafts that hailed from the Netherlands, Germany, France and the Czech lands. The Louvre lent Prague’s National Gallery many works. Some pieces in the collections were being displayed to the public for the first time. A superb small drawing by Michelangelo drew crowds, and art by Hendrick Goltzius, Paul Bril, Aegidius Sadeler and Niccolo Boldrini stood out to me.

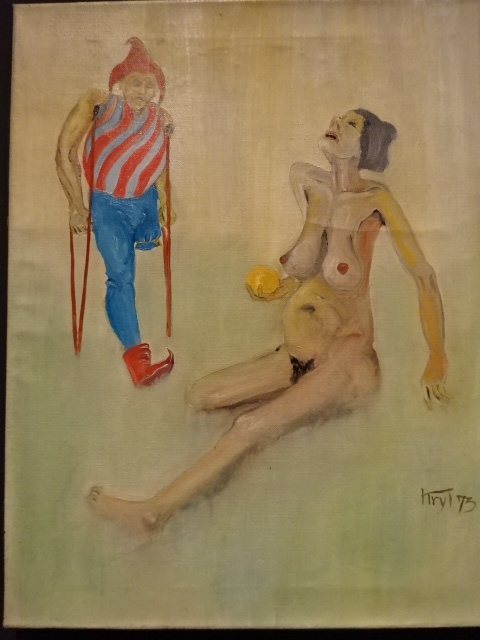

Painting by Karel Kryl, temporary exhibition at House of the Golden Ring

Karel Kryl giving a concert

On my birthday I went to the House of the Golden Ring near Old Town Square. I saw an exhibition about the late dissident singer and songwriter Karel Kryl, whose music had been poetic, profound and political. He had lived in West Germany during much of the Communist era and had worked for Radio Free Europe. I realized how politically-motivated his songs had been and how he had supported the Poles as well as the Czechoslovaks in their fights for freedom. I was engrossed by his artwork, disturbing and grotesque scenes with one-legged clowns and half-human, half-creature figures.

Pieter Brueghel II

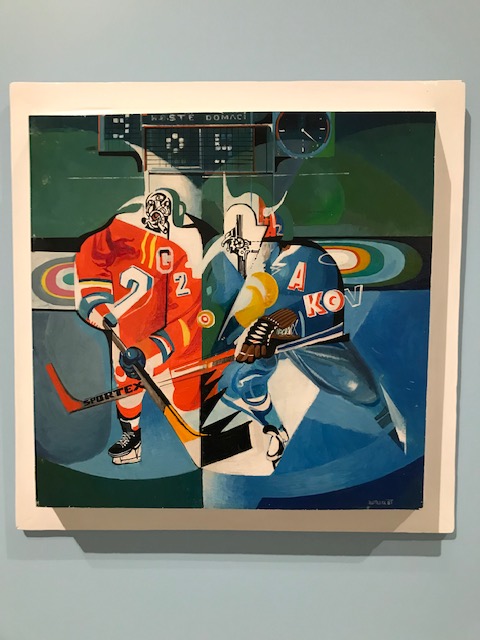

One of my favorite exhibitions of the year, taking place in Kinský Palace, was called “Get on the ice!”, featuring hockey and skating in paintings and other artistic creations. It reinforced the fact that ice hockey and skating have played significant roles in Czech and Slovak identity. I especially was impressed by the works of the Dutch masters who had inspired Czech painting. Pieter Brueghel II’s scene of skating on a pond caught my undivided attention. Czechs first represented skating on the Vltava River and on ice rinks.

Then hockey became the major theme, first portrayed realistically and then in the 1960s expressed in an experimental fashion. I was drawn to František Tavík Šimon’s “Ice Rink Under the Charles Bridge” (1917) with its large falling snowflakes and idyllic, historical setting. One example of the experimentation of the 1960s is Vojtěch Tittlebach’s “Hockey” from 1965, with abstract shapes and simple forms. The players in this painting had no facial traits. Jiří Kolář also added to the experimentation of the 1960s with his “Hockey Sticks,” composed of three wooden sticks decorated with paper collages, many of them maps and some historical scenes. The 1998 Czech Olympic victory at Nagano was celebrated in large photographs, including one that showed the moment Czech Petr Svoboda scored the winning goal while the crowd in Old Town Square erupted in joy.

New Realisms, Karel Čapek from series Cactuses, first half of the 1930s

One-Handed Ice Cream Man, Miloslav Holý, 1923

In Prague I also saw the New Realisms exhibition, which focused on modern Realist trends in Czechoslovak art from 1918 to 1945. The more than 600 works hailed from the Czech and Slovak lands as well as Germany and Hungary. I especially liked Karel Čapek’s photographs of cactuses and his dog Dašenka as this field focused on the everyday during this era. I also liked the many café scenes, realistic portraits of people, magic realism in landscapes, the focus on the societal and economic dilemmas in Czechoslovakia and the depiction of modern labor. I have always been interested in the paintings of Group 42 as their works had an existential quality, often punctuated by telegraph wires and deserted streets.

Francesco Bartolozzi, The Girl and the Kitten, 1787

One of my favorite exhibitions in Prague this past year was called “The Good Cat and the Treacherous One,” featuring cats in graphic art from the 16th to the 18th century. The art shows how some people revered cats while others hated felines. They often symbolized something or were shown for entertainment. Some considered them to be a form of the devil. Others gave them positive religious connotations. I especially enjoyed the Mannerist works by Goltzius and the graphic art by Wenceslaus Hollar, who portrayed cats with both positive and negative qualities. I saw pictures of cats symbolizing maternal love, sight, hearing, devotion, courage, yearning for freedom, foolishness, frivolity, cruelty, greed, treachery, lust and adultery. I also noticed cats as protectors against snakes. A French painting showed how, in 18th century France, cats had epitomized personal and political freedom.

Clam-Gallas Palace

I focused mostly on day trips when traveling this past year. While I visited chateaus, castles and monasteries outside of Prague, I did also become acquainted with the renovated Clam-Gallas Palace in the capital city. The Baroque palace became the property of the Gallas family in the 17th century. The palace has a rich musical and theatrical history as Mozart and Beethoven both performed there during the late 18th century. The colossal exterior portal is decorated with statuary by Baroque master Matyáš Bernard Braun, and he also created the fountain portraying Triton.

Murano chandelier in Clam-Gallas Palace

The many monumental frescoes amazed as did the chandeliers, especially the 19th century chandelier made of Chinese porcelain cups, saucers and vases. Frescoes depict the triumph of Apollo and gathering of the gods on Olympus, for instance. Allegorical figures representing sculpture, architecture and painting stand out in another fresco. I was very impressed with the former office of the first Czechoslovak Minister of Finance, Alois Rašín, though it was sparsely furnished. He had tried to gather support for the creation of Czechoslovakia during World War I and had even been imprisoned for taking part in the resistance. Rašín was assassinated in Prague during January of 1923 by a 19-year old anarchist.

Bohumil Hrabal’s cottage in Kersko

Kersko near Prague is one of my favorite tranquil spots in the country, a village where Hrabal resided from the 1960s until his death in 1997 and where he fed many feral cats daily. Hrabal’s two-story cottage opened to the public for the first time this spring. I saw the garden where he wrote some books and the charming enclosed terrace where he composed his works when weather did not permit him to spend time in his garden. I saw the chair in which Hrabal wrote his last literary piece, during 1995. The top floor was adorned with many paintings – a moving portrait of Hrabal by Jan Jirů, a drawing featuring heads of Hrabal from his youth to old age in a rendition by Jiří Anderle. Another portrayed cats on chairs in a forest setting along with Hrabal himself. Portraits of his family and a collage focusing on one of his books also caught my undivided attention. The place captured the soul of Hrabal, and I was very moved.

In the local shop, known for its ceramic figures of cats, there was an exhibition of drawings of Hrabal – at the pub, in Heaven, in Kersko, each rendition celebrating the author in a creative way. We ate at my favorite restaurant outside of Prague, Hájenka, a prominent landmark in Kersko. Whether I chose the chicken with cheese sauce, the meat with dumplings or the fried chicken steak, I was always delighted by the meal in a rustic, charming atmosphere.

Mariánská Tynice complex

I traveled about 35 kilometers north of Pilsen to pay a second visit to the High Baroque complex with pilgrimage church Mariánská Tynice, an aerial constructed by renowned architect Jan Blažej Santini during the 18th century, using geometric forms such as quadrangles and triangles as features of his Baroque Gothic style. The church with a Greek cross plan had an impressive illusionary main altar of the Holy Trinity while the east and west ambits were constructed with open arcades featuring eight chapels. The masterful painting on the vaulting and walls celebrates the lives of the Virgin Mary and Cistercian saints. The cupola of the church is lit by eight windows.

Frescoes on the walls and vaults of the ambits

Part of the complex was the Museum and gallery of the North Pilsen region. I liked the Gothic altarpieces and Baroque paintings as well as the 19th paintings of pilgrimage sights. The reconstruction of rooms resembling 19th century and early 20th century village life included a classroom, a countryside chapel and a pub.

Museum of the High-Rises, Kladno, ceramic tile on the facade

Gas masks in the nuclear bunker of the Museum of the High-Rises

In Kladno near Prague, I toured the Museum of the High-Rise, which was located in one of the six Rozdělov high-rises designed by Czech functionalist architect Josef Havlíček in the 1950s. He received acclaim during the interwar years as a member of the avantgarde and studied under Cubist architect Josef Gočár. The façade of the 13-floor building was created from ceramic material, and on that particular high-rise were ceramics of a cat and a dog. There was a small museum in one basement floor. We also visited the nuclear bunker, complete with numerous gas masks and many hard benches. The big rooftop terrace was a prominent feature for that time period. In the representative flat for the higher-ups, we saw 1950s furniture and a balcony. The flat measured about 65 meters squared, quite a luxury in that day and age.

Humprecht Chateau

View from Humprecht Chateau

I also visited many chateaus within a two-hour distance of Prague. Seventeenth century Humprecht Chateau in the central Bohemian Paradise region had an elliptical shape. Much of the interior featured hunting themes. I saw paintings of Venice, Biedermeier bookcases in the two libraries of about 4,000 volumes, a black kitchen with an original fireplace and utensils from the 17th century. The main hall featured four frescoes from the 1930s, showing scenes from the life of the Černín family, the long-time owners of the chateau. Baroque furniture decorated several rooms. The picture gallery includes works from the 17th century. What I liked best about the chateau were the panoramic vistas from the top floor.

Volman Villa

Also, not far from Prague, the newly reconstructed Volman Villa, a large, geometric functionalist structure built from 1938 to 1939, featured big terraces, a circular driveway, a monumental winding staircase and outer stairs that lead to a bridge heading into the building. It is possible to access the terrace from each spacious room. Volman used exotic materials such as travertine and marble for the construction. The marble bathrooms with beautiful pink and light blue bathtubs were vast. While there are now many trees obstructing the view, at one time it was possible to see the Labe River in the 40-hectare English park.

Grabštejn Castle, Chapel of Saint Barbara

I visited several castles and chateaus in north Bohemia – Grabštejn Castle, Jezeří Chateau and Červeny Hrádek Chateau. I was shocked at the vast improvements made during the reconstruction of Grabštejn and Jezeří as I had last visited the two about 20 years ago. Grabštejn, originally a 13th century castle, took on the structure of a Renaissance chateau in the 16th century. The 16th century Chapel of Saint Barbara featured exquisite vaulting and wall painting that included 13 apostles. One tour featured the 18th century administrative offices that made up the castle interior during that time period while another showed the rooms of the nobility, including a gigantic wall painting with chateau-like gardens and fountain. I saw furnishings and artifacts from the 16th to 19th centuries.

Jezeří Chateau, painting by Carl Robert Croll

While only a few rooms of Jezeří Chateau were opened about 25 years ago, now there are about 10 impressive spaces on the tour. I loved the paintings of Carl Robert Croll, renditions which showed the interior of the chateau during the early 19th century. I was especially impressed with the room dedicated to Jan Masaryk, the son of the first president of Czechoslovakia and once the Minister of Foreign Affairs. He was thrown out a bathroom window at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs by the Communists after the 1948 coup. The Winter Garden was light and airy, punctuated by much greenery. The lavish Theatre Hall included sculptural and stucco adornment as well as an original fireplace. The paintings throughout were impressive, too.

Červený Hrádek, Knights’ Hall

Červený Hrádek dated back to the early 15th century and gets it current appearance from the 17th century. The Knights’ Hall from that era included lavish sculptural decoration with medallions featuring battle scenes and exquisite crystal chandeliers. Other spaces harkened back to the 18th and 19th centuries with period furnishings. Seventeenth century sculptor Jan Brokoff created sculptures, fountains and vases that decorated the monumental staircase. The English style park was beautiful, too. In August of 1938 the Sudeten Party leader Konrad Henlein and English Lord Walter Runciman had a meeting there, shortly before the Munich Agreement was signed.

Dobříš Chateau Park

Dobříš Chateau Park

Because the interior had been recently renovated, I returned to Dobříš Chateau not far from Prague. I was disappointed there were not as many rooms decorated with period furniture. Instead, the self-guided tour mostly featured spaces celebrating the Colloredo-Mansfield family’s accomplishments, which were very intriguing and noteworthy, to be sure. Still, I missed the longer, guided tour and former exciting interior décor of the Rococo and Classicist eras. The Writers’ Room remained on display, decorated the way the space would have looked when the chateau belonged to the Writers’ Union from the 1950s to the 1990s. It was possible to enter one side of the spectacular Hall of Mirrors, although it was roped off and walking through the room was not permitted. The fresco-filled hall amazed with 18th century décor and eight Venetian chandeliers as well as monumental fireplaces.

Illusionary painting on the orangery in Dobříš Chateau Park

The park, measuring nearly two hectares, was the reason to visit the chateau. On that sunny summer day, it was spectacular to stroll through the Rococo style park established in the 1770s. It had five terraces, a fountain with astounding Baroque sculptural grouping and an orangery with illusionary wall painting.

Slatiňany Chateau

Interior of Slatiňany Chateau

I traveled to Slatiňany Chateau for the second time and noted the prominent hunting and horseback riding themes. The Auerspergs held on to the chateau for 200 years and were responsible for the charming interior. I loved the exquisite canopied beds decorated with religious paintings. The tapestries were another delight. In the Big Dining Room I admired a large painting of hunters and their dogs getting ready for the hunt as well as a stunning 18th century Murano chandelier.

Vienna, Albertina, Monet, Waterlillies, in the permanent collection

I had many exciting adventures traveling in 2024 and had many impactful experiences at art exhibitions in the Czech Republic, Germany and Austria. Every time I go on a trip or to an art show, I come away changed, with a sharper perspective on life and with more enthralling knowledge.

Albertinum, Dresden, Hans Grundig, The Thousand-Year Empire, in the permanent collection

Tracy A. Burns is a writer, proofreader and editor in Prague.