It was my second visit to Vranov nad Dyjí, one of my favorite chateaus, located near Znojmo in south Moravia. Its façade was a hodgepodge of at least three architectural styles. Some medieval elements of the Baroque chateau had been preserved. The Crow’s Tower and the building in the first courtyard harkened back to the Middle Ages. The Baroque fountain was spectacular. I had to stop to admire the garden bursting with color as I walked toward the chateau. The white and yellow Baroque church with belfries was perched on a cliff to the left and below the chateau. It looked to me that it was positioned precariously, as if it would fall off the edge at any moment.

The chateau, part of Podyjí National Park, blended in with the cliffs and picturesque countryside, a characteristic that I found attractive. Vranov nad Dyjí did not disturb nature but rather complemented it. I felt comfortable here in this stunning, natural environment. The rooms were small and intimate (except for the vast Ancestors’ Hall) and were filled with exquisite objects. All the items gave the chateau a unique identity without one artifact overwhelming the others.

I was already familiar with the history of the chateau. Vranov was first mentioned in the Kosmas Chronicle during 1100. Originally, it served as a fortress made of wood and became a stone castle at the end of the 13th and during the 14th century. There were additions made in the 15th century, but in 1665 it succumbed to flames. When Michal Johann II von Althann bought it in 1680, the chateau stayed in the family for more than a century. Michael Johann II made it into a Baroque chateau. Under his guidance the astounding Hall of Ancestors and the chapel were built. Later, the chateau became a three-wing residential palace. Neo-Gothic and Romantic style elements were added during the 19th century. During that century, it was the property of two Polish clans – the Mniszek counts and the Stadnickis. The state took control of the chateau after 1945.

Waiting for the tour to begin, I was overwhelmed by the two-flight Baroque main stairway decorated with sculptures. Hercules battled the giant Antaeus. Prince Aeneas carried his feeble father from burning Troy. Then 15 young children scampered toward me. It was my worst nightmare. I was worried that all these children would accompany me on the tour of my beloved chateau, and I would not be able to hear the guide over their cries. At least that had been my experience when visiting other chateaus with groups of young children.

Waiting for the tour to begin, I was overwhelmed by the two-flight Baroque main stairway decorated with sculptures. Hercules battled the giant Antaeus. Prince Aeneas carried his feeble father from burning Troy. Then 15 young children scampered toward me. It was my worst nightmare. I was worried that all these children would accompany me on the tour of my beloved chateau, and I would not be able to hear the guide over their cries. At least that had been my experience when visiting other chateaus with groups of young children.

Finally, the tour began. The guide, a tall, lanky, serious blond woman in her early twenties, ushered me and the children as well as a few other adults into the Hall of Ancestors. It took eight years to complete the lush décor of this space with its walls and ceiling covered in breathtaking frescoes celebrating the Althann family. Its stunning beauty made me dizzy. I looked up and noticed a golden chariot floating on the clouds. The female charioteer symbolized the Earth’s fertility, the guide explained. Between the oval windows I could make out the figures of Hercules, Orpheus, Theseus, Odysseus and Perseus praising the Althann ancestors. The family members’ statues decorated the niches of the hall. I was amazed by something else, too. None of the children were misbehaving. Some mumbled to themselves, but they were all fairly quiet and seemed interested in the guide’s descriptions. Maybe they would not be so badly behaved, after all.

Next we went outside onto the terrace, created at the end of the 18th century. The children loved the cannon balls there. The guide explained that the Swedes tried to take over the chateau twice during the Thirty Years’ War in the 17th century, but failed to do so. I peered at the valley and romantic landscape that surrounded the chateau. The scenery was postcard perfect. It was so peaceful and tranquil. I could have stared at the landscape forever. Standing there, looking at the countryside of south Moravia, I found inner peace. Perhaps that is why I loved this chateau so much. Here, I found a sense of inner peace, calmness and strength to take on future trials and tribulations.

Then it was time for the residential rooms, furnished as they were at the end of the 18th century and throughout the 19th century. In the tiny entrance to the Pignatelli bedroom, a space that could not fit all the children, I saw a painting of Vranov five years before it was engulfed by flames in the 17th century. I was especially drawn to the scraggly cliffs and the meandering river in the picture as well as to the stone bridge that I walked on earlier today. Then we entered the main room, which was once the private chapel. A moustached man told a few rambunctious children to be quiet. The room exuded a sense of symmetry so typical of the Classicist era. I noticed the exquisite fabric texture of the wall hangings, decorated with hunting themes and picturesque landscapes. Two statues inspired by antiquity flanked a canopy bed and stood on pedestals. I was enamored by their exquisite green leaf motifs.

The next space had been a dining room since the 1720s. The printed stoneware on the table featured the Italian town of Ferrara and came from the prominent Vranov earthenware factory founded in the 19th century. I was filled with awe as I took in the pictures on the wall. The hand-painted canvas showed landscape views of a park with ancient, medieval, Chinese and Egyptian structures. The guide pointed out a scene showing the Park Monceau in Paris. Holy Roman Emperor Charles VI, whose tenure on the throne lasted from 1711 to 1740, made an appearance in the scene. No stranger to the Althann family, Charles VI was a close friend of Marie Anna, who was an owner of the chateau in the second half of the 18th century. The emperor had even visited Vranov. Two children were scolded for pushing each other.

In the Family Salon the owner’s relatives and guests would discuss private and public topics after a meal. They played cards or chess, read books, listened to music and sipped coffee, tea or hot chocolate. A samovar tea urn from Russia’s Tula town attested to this ritual. The white-grey and pistachio colors of the wall fabrics entranced me. They showed Pompeii and other ancient towns. A young girl with bright blue eyes giggled.

The Blue Salon, the ladies’ living room, exuded a Classical style with its blue wall hangings and two sculptures of Aphrodite on white stoves. The furniture, an elegant blue mahogany, hailed from the 19th century and was made in Empire style. There were various kinds of porcelain – Viennese and Meissen, for example – in the room as well. The children began to appear restless, no longer paying much attention to the exhibits.

The Respirium was where the family relaxed after taking a bath. The wall and ceiling décor fascinated me. The Classicist relief stucco and ornamentation featuring carved wood was so elegant, and I felt so comfortable in this space. The white columns had hidden compartments where toiletries were kept. I loved the stucco decorations above the door. In one scene, Artemis, goddess of the hunt, was being watched by Actaeon, who happened to be hunting in the forest when he saw her naked. Artemis turned him into a deer that her dogs devoured. I was glad that I was able to hear the guide as the children talked and argued among themselves. One girl with long chestnut-colored hair who would someday turn into a very beautiful woman began to cry.

The Respirium was where the family relaxed after taking a bath. The wall and ceiling décor fascinated me. The Classicist relief stucco and ornamentation featuring carved wood was so elegant, and I felt so comfortable in this space. The white columns had hidden compartments where toiletries were kept. I loved the stucco decorations above the door. In one scene, Artemis, goddess of the hunt, was being watched by Actaeon, who happened to be hunting in the forest when he saw her naked. Artemis turned him into a deer that her dogs devoured. I was glad that I was able to hear the guide as the children talked and argued among themselves. One girl with long chestnut-colored hair who would someday turn into a very beautiful woman began to cry.

Next we saw the Classicist bathroom, hailing from the 18th century. Artificial marble lined the walls. I loved the four black columns that appeared so elegant without being extravagant. The guide, her voice a bit hoarse now, explained that the central pool had been used as a bathing area, but now visitors threw coins in the water for good luck. The children became excited and pleaded with the adults to give them some change. The chaperones shook their heads.

Hailing from the 18th century, a Rococo screen with Chinese motifs took precedence in the Oriental Salon. On the screen I could make out oriental gardens with bodies of water and paths. An aristocratic couple was celebrating around exotic figures. I was fascinated by the three unique sections of a 19th century Chinese scroll preserved in three rectangular frames. The scroll depicted a poet who had lived in the third century. The scribbler was coming home after being captured by the Huns. The scrolls showed her Hunnish escort, musicians and a general riding under a canopy while the poet held a child under a royal standard. This time a few of the children appeared interested in the scenes on the scroll as they talked among themselves about ancient battles.

Next came the Pompeii Salon with graphics on the walls depicting interiors of ancient palaces and villas. Vranov stoneware made a prominent appearance here. My eyes wandered to a pink vase with green décor. How I would love for my mother to be able to see that! She would love that vase! Maybe some day she would, I told myself. I wanted to show my parents so much of this country, but I would never have the chance to show them everything. The children showed no interest in the space.

The Althann Salon was another delight. Many of the paintings depicted members of this family, so significant to the development of the chateau. I admired the Baroque traveling altar. Brightly colored Vranov stoneware from the 19th century could also be found throughout the salon. By now the children were whining, restless, ready to leave.

The Gentlemen’s Salon hailed from the 19th century, and the decorations were inspired by spiritual alchemy. The scene above the door showed two female figures sleeping. Naked figures above four landscapes held torches. The symbols under the landscapes were focused on the Freemasons. The compasses and the square represented the meeting of heaven and earth, the guide remarked over a din of children’s cries. I admired the four landscapes on the walls, especially the depiction of the waterfall. I could almost hear the cascading water. The youngsters were not able to sit still.

The Swiss Rooms with 19th century landscape paintings on the walls were the next stops. I recognized Hercules in the midst of a battle. A black-stained cabinet was inlaid with marble depicting castles, towns, and rocks. The Picture Gallery included paintings by Dutch and Austrian artists from the 17th to 19th centuries. The Study was decorated with 19th century symbols of alchemy.

Last but not least came the library rooms. Created at the beginning of the 19th century, they now housed some 10,000 volumes. The black cabinets with geometrical designs looked sleek. Most of the books were written in French, German and Polish and hailed from the 18th and 19th centuries. The volumes consisted of both fiction and non-fiction that included subjects such as philosophy, mathematics, geography, theatre and history. I gazed at Voltaire’s collected works in cabinet 13.

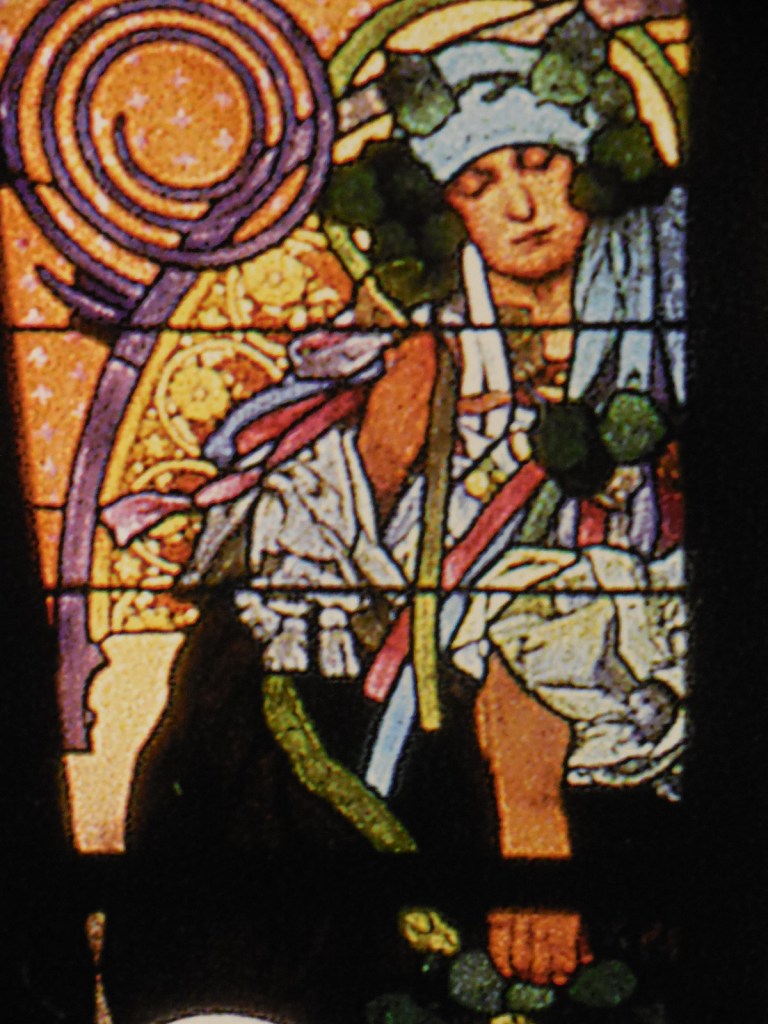

Soon the tour was over. The children and their escorts scrambled away, and I took off toward the Chapel of the Holy Trinity in its romantic setting on the edge of the cliff below the chateau. It was hard for me to believe that this impressive structure was completed within two years (1699-1700). Relieved that the children were not going to the church, I turned out to be the only one on the tour. I overheard a couple above the stairs leading down to the chapel.

“Do you want to see the chapel?”

The answer: “No, it does not seem so interesting.”

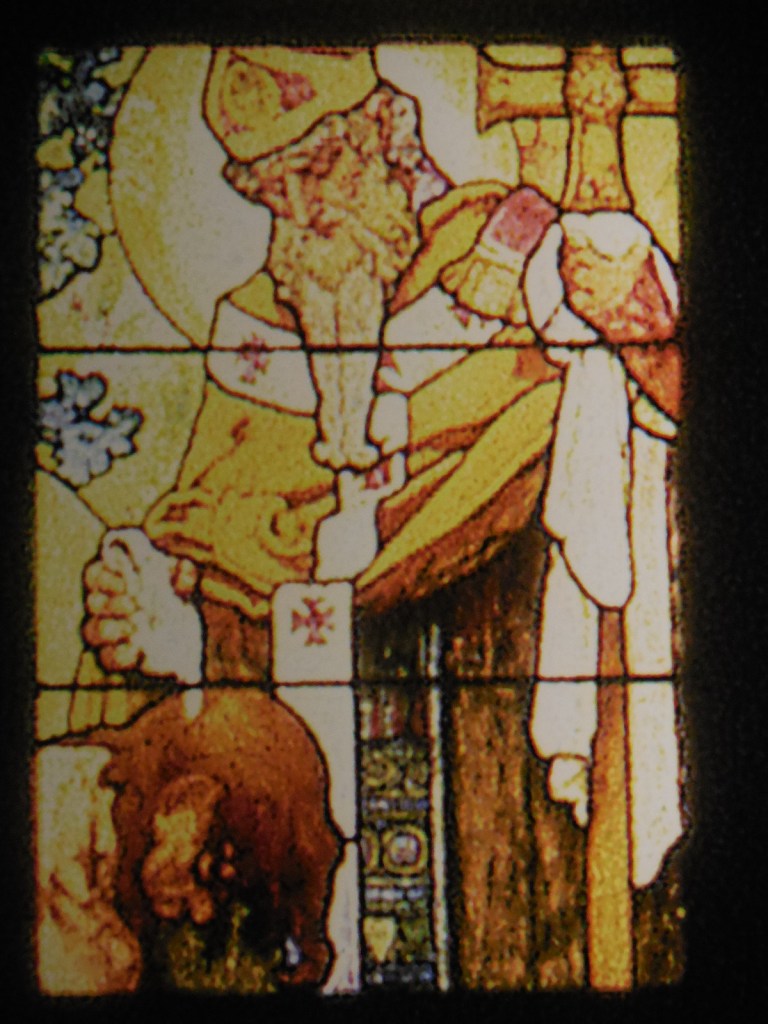

That couple did not know what they were missing. Architecturally, the interior had a central cylindrical nave with six oval rooms. There were three altars. Notably absent from the main altar was a picture or any kind of centerpiece. I had never seen a main altar like that before. I liked it because it was unique. I could see the Holy Trinity, and a pigeon represented the Holy Spirit. Angels also appeared in the Baroque creation, and golden rods shot out of the work.

That couple did not know what they were missing. Architecturally, the interior had a central cylindrical nave with six oval rooms. There were three altars. Notably absent from the main altar was a picture or any kind of centerpiece. I had never seen a main altar like that before. I liked it because it was unique. I could see the Holy Trinity, and a pigeon represented the Holy Spirit. Angels also appeared in the Baroque creation, and golden rods shot out of the work.

The fresco in the cupola celebrated Archangel Michael, the defender of the Catholic Church, wielding a sword as he defeated Satan. Victorious, he placed his foot on his opponent’s chest. Angels danced and swirled around him. One side altar showed Saint Sebastian struck with arrows and Saint John the Baptist accompanied by sheep. The other altar portrayed Saint Barbara with a tower and Saint John with an eagle, holding a book. The Virgin Mary wore golden, flowing drapery.

Oval panels above the altars dealt with themes such as Heaven, Paradise and the Last Judgment. The panel depicting the Last Judgment featured skeletons. One skeleton’s gesture seemed to be saying, “What? Me?”

After the tour of the church, I gazed at the romantic countryside and at the elegant chateau that blended with its surroundings, becoming a part of nature yet still retaining its own identity. Yes, I felt at peace here, even when among the rambunctious children on the tour. This place gave me strength that I often lacked. In the countryside here I also found a sense of hope. The panorama gave me energy and a sense of optimism.

I left, reluctantly, to walk down the steep hill to the village below. From there the bus would take me back to Znojmo, where I would see a castle with magnificent interiors, a stunning rotunda, a spectacular church and several picturesque squares. I would stay in that intriguing south Moravian town overnight before heading back to Prague.

Tracy A. Burns is a writer, proofreader and editor in Prague.