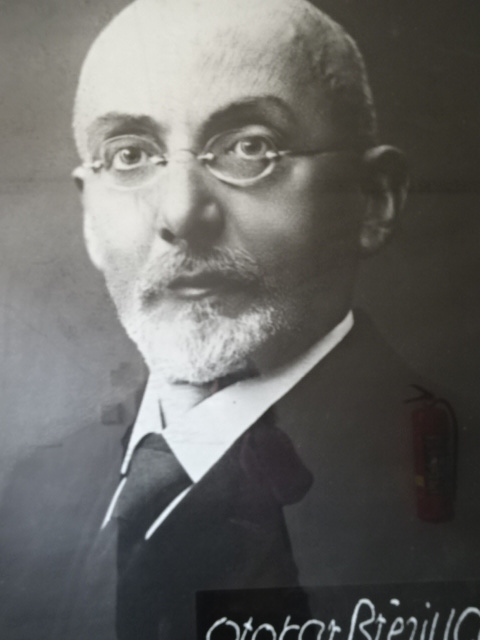

Although I hold a M.A. in Czech literature, I wasn’t very familiar with the poetry and essays of Otakar Březina before visiting the museum, located in the three-room apartment where he had lived and died. (I had focused on the Czech fiction of four writers for my master’s thesis.) I was excited to get to know about the life and work of a Czech writer whom I only knew by name. The guide even mentioned that Březina had been in the running for the Nobel Prize eight times, but hadn’t ever won.

Otakar Březina

The man who would greatly influence 20th century poetry was born Václav Ignác Jebavý in the village of Počátky on March 25, 1929. After graduating from high school in Telč, he became a teacher, working for a while in Nová Ríše. However, all was not rosy. His feelings of isolation and solitude from this time would make major appearances in his poetry. He got his teacher’s degree in Prague and taught in a Moravian town from 1888 to 1901.

14-year old Otakar Březina

Then double tragedy hit. Březina was devastated when both his parents passed in one week during February of 1890. At this time, he experienced severe bouts of depression, loneliness and solitude. These tragedies played roles in his writings and thought processes, too.

The desk of Otakar Březina

In 1901 he moved to Jaroměřice. Březina got to know many writers, including Karel Čapek, who had visited Jaroměřice on more than one occasion. He also made friends with poet, prose writer and priest Jakub Deml as well as philosopher and novelist Ladislav Klíma, who, like Březina, was influenced by Arthur Schopenhauer and Friedrich Nietzsche.

The bed where Otakar Březina died

Březina retired in 1925. Four years later, he would die of heart complications in the narrow, single bed that I saw in his former home. The President of Czechoslovakia, Tomáš G. Masaryk sent Březina a doctor who said that nothing could be done. Březina died in his narrow single bed two days later. He was buried in the nearby cemetery. Bílek designed his impressive grave.

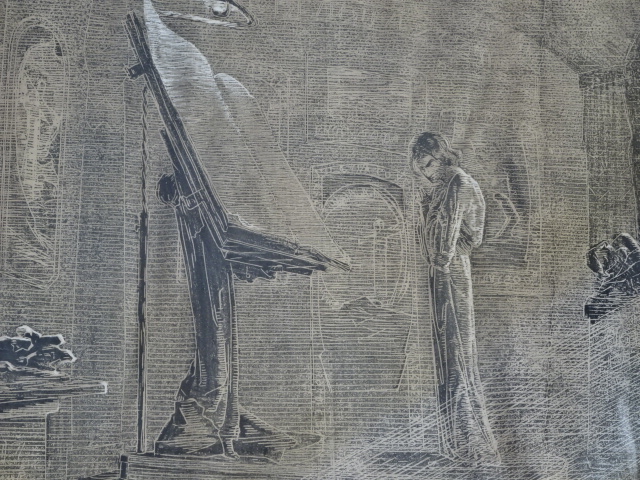

Painting in the flat of Otakar Březina

In the first floor flat, I saw intriguing furniture, paintings, graphic art, photos, correspondence, diplomas and editions of Březina’s books as well as biographies about him. More than 4,500 volumes of his work were housed in a museum in Brno, the capital of Moravia. In this museum, though, the collection of volumes was noteworthy. In fact, downstairs there was a small library dedicated to the Symbolist writer. In the display cases of his first floor apartment, I spotted several of his books in English as well as many old Czech editions. I studied the pictures of him as a child and teenager. I had read that he had experienced much suffering as a child because he had no one to help him. He had to do everything for himself.

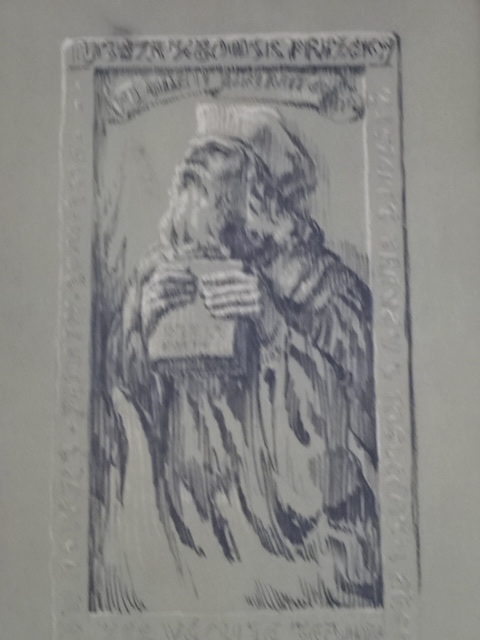

Art by František Bílek in the flat

I liked best the artwork in his flat, especially that by Symbolist sculptor František Bílek, who had been a close friend. I fondly recalled my many visits to Bílek’s villa in Prague. It was an architectural gem punctuated by his sculpture, furniture and more. His works were emotional, symbolic, religious and mystical.

Another artwork by Bílek in the flat

Bílek, born in 1862, initially wanted to become a painter but switched to sculpture because he was colorblind. He would wind up making a name for himself not only for his evocative sculptures but also for his prints, architectural designs, ceramics and books, for instance. A man of many talents, he was very religious, and the works of the Catholic Modernists greatly influenced his works. He later worshipped at a Czechoslovak Hussite Church, inspired by the teachings of Czech martyr Jan Hus who was burned at the stake for heresy in 1415.

More art by Bílek in the flat

I had also visited Bílek’s hometown of Chýnov in south Bohemia, where his villa there housed more of his fascinating creations. It was easy to find his grave in the cemetery there – a huge sculpture marked the spot. Bílek passed away during the Nazi Occupation, in 1941.

Another work by Bílek in the flat of Otakar Březina

Back to Otakar Brezina. He started writing during high school in Telč from 1883 to 1887. Back then, he penned stories and feuilletons with a small town environment. His poetry was first published in the magazine Vesna during 1886. As a young author, he was inspired by Jan Neruda, who made his characters come alive in stories about the Lesser Quarter in Prague, for instance. The small town atmosphere was prominent in Neruda’s writings. The future leader of Symbolist poetry decided to use the pseudonym Otakar Březina after he spotted the name on the door of a house, and from 1892 he wrote under that name.

Another masterpiece by František Bílek in the flat

His poetry was philosophical, symbolic, mystical and religious with complex metaphors. The theme of looking for God played a prominent role. He often wrote about depression, suffering, sadness as well as the conflict between dreams and reality.

Art in the flat of Otakar Březina

At first Březina wrote mostly prose, often dealing with death and loneliness. This period of his career was greatly influenced by the passing of his parents. Březina suffered bouts of depression and had a negative attitude to reality, shaped by Schopenhauer’s ideas. Březina used symbolism more often in his works and turned to poetry. His poems were punctuated by secrets, symbolism, mysticism and religion. His search for God was symbolic. He believed that death symbolized a new beginning and opened up a new path. He wrote about the material and spiritual worlds, faith and love, and sometimes he addressed the social problems of his era. Březina also wrote essays in magazines during the early 1900s, focusing on art and life.

Furniture in the flat

After World War II, the town of Jaroměřice owned Březina’s former apartment. In the 1950s the Communists had all the artifacts moved to a museum in another town. The building was in poor condition and remained that way for a long time. After the 1989 Velvet Revolution, reconstruction took place, and the museum was revived. The newly-opened home of the Symbolist poet was inaugurated September 11, 1993, owned by the Society of Otakar Březina. In 2005 the museum received more recognition, becoming a cultural monument.

Part of the garden dedicated to Karel Čapek

The Garden of Symbols

In 2011 the museum opened the Garden of Symbols in its small but impressive garden dedicated to Otakar Březina, Jan Adam Questenberk (who owned the town’s chateau during its heyday), Bílek and Karel Čapek, for example. A path through the garden looked like it came to an end when it suddenly continued to the left, symbolizing immortality because the path did not end just as death did not end in Březina’s philosophy. Reconstruction of the garden took place in 2017 and 2018, the year it opened again. It was masterfully planned to represent Březina’s works, writing style and life as well as acknowledging other famous historical figures who had influenced Březina and the town.

The sign denoting the tree dedicated to Jan Adam Questenberk, the owner of the chateau during its golden age

We also went to a gardening center that first opened in 1901, a store where Karel Čapek had bought plants. Still in business, it offered customers a wide variety of plants in a large space. Cats reclined in baskets near the cash register.

One of the cats at the gardening center

This was one of the best sights I had visited, even though it contained only three rooms. Literary landmarks were close to my heart. I learned so much about Březina and saw so many astounding artworks. We also saw the chateau and the Church of Saint Markéta that day, making for a wonderful trip.

Tracy A. Burns is a writer and proofreader in Prague.

Otakar Březina

Otakar Březina

Flowers in the Garden of Symbols