During the fall of 2024, I went to the Paul Gauguin retrospective “Gauguin Unexpected” in Vienna, Austria at the Kunstforum Wein. The last extensive showing of Gauguin’s works in Austria had taken place during 1960. The recent exhibition included not only Gauguin’s paintings but also graphic art and sculpture, tracing his career from Post-Impressionism to the initial stages of the modern era. More than 80 works were on display from October of 2024 to January of 2025.

Eugene Henri Paul Gauguin was born in Paris on June 7, 1848, the revolutionary year of turmoil in Europe. At the age of 18 months, he and his parents moved to Peru because his father had to leave France. He was related to high-ranking politicians there. However, his father died during the voyage and never made it to Peru. Gauguin and his mother lived a privileged life there. Due to political turmoil in Peru, Gauguin returned to France when he was still a child. Gauguin would serve in the French navy before becoming a stockbroker at age 23.

In his early career, he worked in Impressionist style and had exhibitions of works in this style during the early 1880s. He worked as a stockbroker for 11 years, and in 1873 married Mette-Sophie Gad from Denmark. They had five children. His marriage fell apart in 1882, when he turned to painting full-time, a time when stock market prices plummeted. He lived in Rouen and then Pont-Aven, where the works of Vincent Van Gogh, Georges Seurat and Eduard Degas impressed him so much that he changed his style. His Post-Impressionist works were unique in use of color, which was the dominant feature of the paintings. His thick and bold brushstrokes also played a major role.

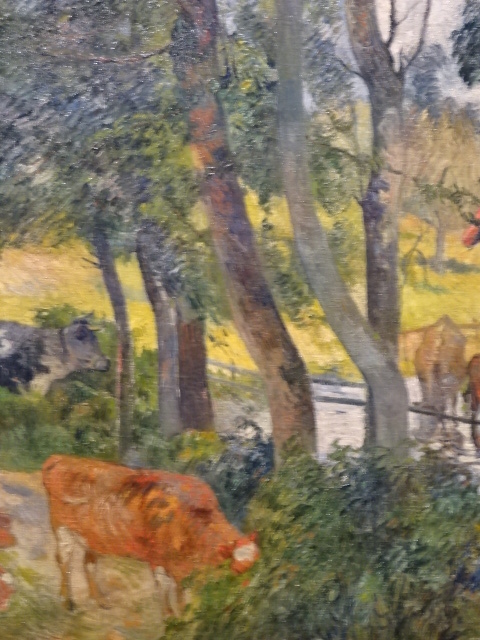

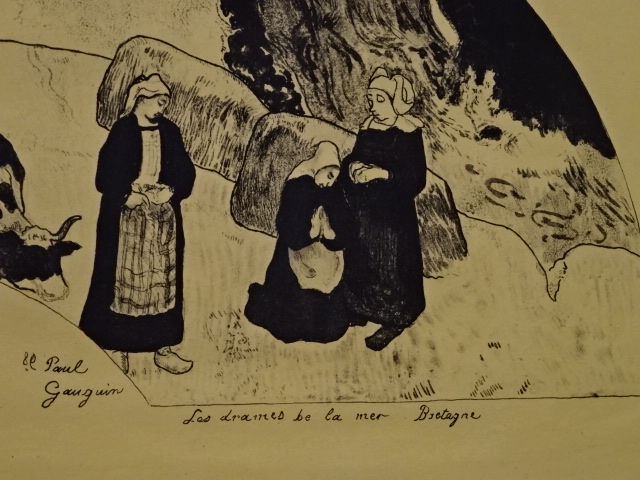

In the summer of 1886, he was influenced by the Pont-Aven School and spent time in Brittany, where he created many landscapes and pastel drawings. I liked his Brittany-based landscapes from this period as well as the scenes of everyday life in this region of France. His employment of Synthesist features comes from this time period of bold colors and dark outlines. Complexity was absent in the subject matter of this time in his career. He pictorially recorded simple, daily life in Brittany. He also thought that African and Asian art held great significance. Japanese art especially enthralled him. Then travels took him to the Panama Canal and Martinique, where he was influenced by Indian people and Indian symbols. His landscapes from his tenure in Martinique are very noteworthy, as I found out at the exhibition.

For a while, he lived with Van Gogh at Van Gogh’s Yellow House in Arles. Van Gogh had bought three of Gauguin’s paintings and held him in great esteem. However, the two had a falling out, and Van Gogh even cut off his ear when Gauguin was present. That’s when Gauguin left Arles.

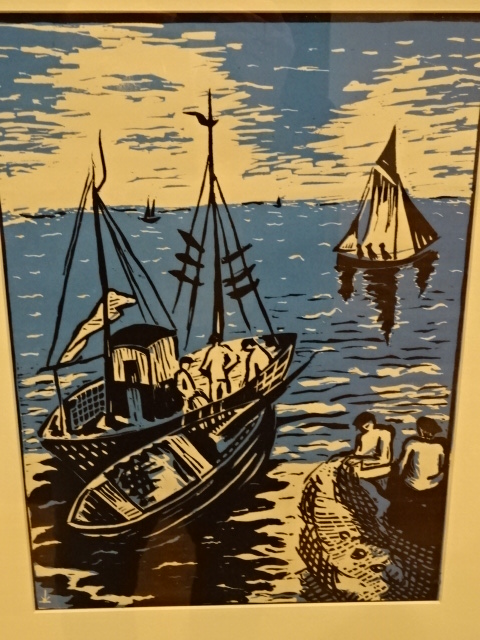

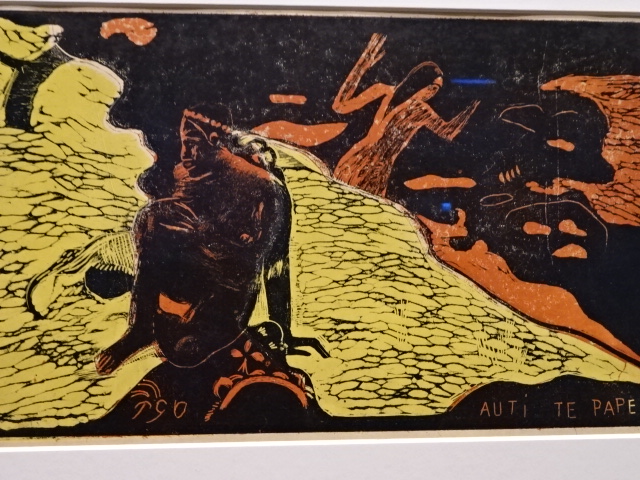

In the late 1880s, Gauguin began making zinc plates or zincographs. Rejecting the traditional limestone material, he opted to use zinc plates combined with yellow poster paper, which made for bold creations in bright yellow. One of my favorite features of this exhibition was the number of zincographs displayed. Some showed female forms with black outlines on a bright yellow background. The result was stunningly bold and brazen.

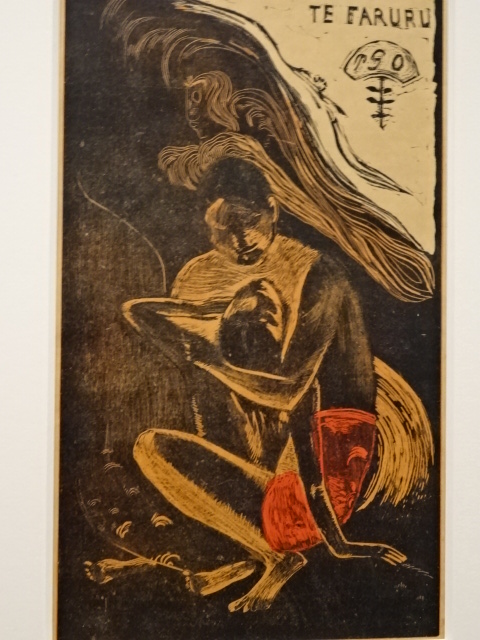

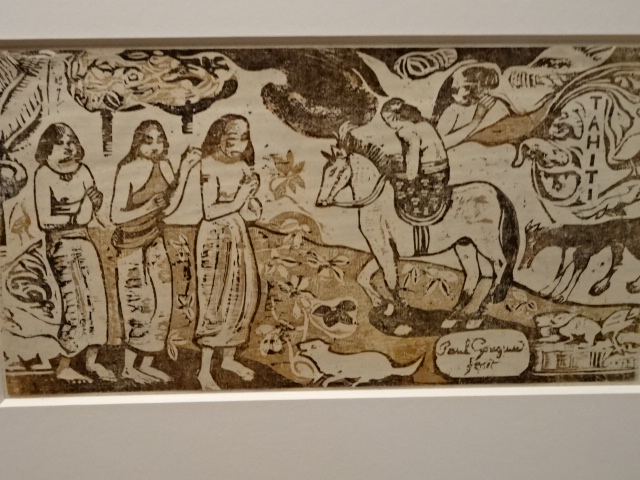

Entranced with the exotic and a supporter of colonialism, Gauguin wanted to flee from Western civilization. After six years in Tahiti, which was under French colonial rule that took advantage of natives, Gauguin left but decided to settle again in the Polynesian Islands during 1895 and never to return to Europe. His works showed off the Primitivism style as he depicted island natives as well as gods in the traditional religion via painting and sculpture. The colors were brash, overly aggressive, the settings wild. His figures did not have realistic boy proportions and showed off geometric qualities. In Tahiti he often produced his works on a rough surface, such as sackcloth or hessian. He used thick and bold brushstrokes. His Primitivism style would greatly influence Pablo Picasso’s works. I was impressed how the exhibition did not fully focus on his time in Tahiti but took into consideration his entire career equally.

Gauguin experienced problems with his heart, sight and ankle, for instance. He took morphine for the pain. At the end of his life, he spent much time writing as his pain sometimes did not permit him to paint. On May 8, 1903 Van Gogh died from syphilis in the Marquéses Islands at age 54.

A sign at the entrance to the exhibition addressed Gauguin’s sexism and promotion of post-colonialism, inviting people to look at Gauguin’s work in these contexts. Gauguin had married three young teenagers at various times while living in the Polynesian Islands. Gauguin’s use of Primitivism showed Polynesian women in a racist way, and his works from this era pictorially asserted the power of colonialism. I was impressed with the curator’s attention to the present perspectives.

Overall, I was most impressed by the Brittany and Martinique landscapes as well as by the zinc plates. I had mostly seen Gauguin’s work from his Tahiti tenure. I was glad to get an overview of his work throughout the decades and to see how he developed as an artist in a chronological manner. His use of vibrant color and bold brushstrokes also spoke to me.

Tracy A. Burns is a writer, proofreader and editor in Prague.