The Holy Shrine of St. John of Nepomuk, Zelená Hora

For some years I had wanted to go on a tour of places designed by Jan Blažej Santini-Aichel, an 18th century Czech architect of Italian origin, who lived from 1677 to 1723. I am fascinated by Santini’s unique Baroque Gothic style, inspired by the Italian radical Baroque use of geometry and symbolism. I see Santini’s structures as rational yet radical. Santini elevates Gothic art to a new form, offering fresh perspectives and giving new insights.

Jan Blažej Santini-Aichel

Santini was supposed to follow in his father’s footsteps and become a stonemason, but palsy prevented him from doing so. As a student he was mentored by Prague-based architect Jan Baptiste Mathey. During a four-year sojourn in Italy, Santini became enamored with works by Italian architects Francesco Borromini and Guarino Guarnini and their radical Baroque style. Santini was commissioned to reconstruct many religious sites. Baroque art became the fashion during the era when the Catholic army triumphed in the Thirty Years’ War and remained so afterwards, when the Catholicism flourished in the Czech lands. During a mere 46 years, Santini cast his magic spell on about 80 buildings.

So, when I got the opportunity to travel with Czech tour company arsviva to Santini’s sites in eastern Bohemia and Moravia, I jumped at the chance. I was not to be disappointed.

The facade of the Church of the Assumption of Mary and St. John the Baptist

We began our tour where Santini had launched his Baroque Gothic style, with the Church of the Assumption of Mary and St. John the Baptist in central Bohemia’s Sedlec, near Kutná Hora. The monastery hailed from the middle of the 12th century, when it was a Romanesque style church. It burned down during the 15th century Hussite Wars and would not get a makeover for 278 years.

The interior of the Church of the Assumption of Mary and St. John the Baptist

Then, during the 18th century, the 25-year old Santini worked his magic on the largest church in the Czech lands. The façade featured a portico with a triple canopy. A four-leaf rosette decorated the gable of the façade. A large window allowed the light to stream in and give the space a unique character. I had never realized that light played such a major role in Santini’s structures until I saw how it made this church so dynamic.

The vaulting in the main body, the transept and choir boasted a network of circular ribs. The gallery and side body featured dome vaults divided by lancet rib bands. There also was a self-supporting staircase, another common element in Santini’s designs.

I loved the ceiling vaulting. The complex network of vaults reminded me of the complex situation Czechoslovakia had found itself in not long after the Velvet Revolution, when I moved to Prague in 1991. It had been an exciting time as Czechoslovakia had tried to find its own identity in a democratic system. Czechoslovakia would soon split apart, unable to negotiate the difficult roads. I, too, had been trying to find my own self-identity, not a simple matter, either. But I like to think, that unlike the situation with Czechoslovakia, I found my way through the network of vaults.

Next stop: Želiv Monastery Church of the Virgin Mary’s Birth. The monastery was founded in 1139. Santini’s designs were implemented here from 1714 to 1720. This time Santini was not changing the structure into his unique Baroque Gothic style. He had another building constructed and connected it to a Gothic chancel that he had renovated. A Gothic monstrance made of wrought iron shows off in Santini’s style. The three naves with galleries were separated by hanging pendant keystones. This feature gave the space a sense of fragility.

Želiv Monastery’s Church of the Virgin Mary’s Birth

The two 44-meter high clock towers close a polygonal arcade antechamber, one feature of Santini’s designs. The façade has a triangular gable. The wooden Baroque main altar dated from 1730, with a picture of the Birth of the Virgin Mary and symbols of the four evangelists. There were gilded reliefs on the altar under the statues of prophets. Behind the altar was an original Gothic sanctuary. The organ dated from 1743. Most of the interior furnishings hailed from the first half of the 18th century, after the devastating fire of 1712.

Želiv experienced harsh times during the totalitarian regime. In 1950 the Communists shut down the monastery and transformed it into a detention camp for monks. Then in 1957 it became a psychiatric institution and remained so until 1992. The monks were able to return in 1991.

Church of the Assumption of Our Lady in Žďár nad Sázavou

Then we traveled to Žďár nad Sázavou, where a monastery had been erected in the 13th century. I had visited the monastery some years earlier to see a museum devoted to books. I will forever recall excitement of seeing a 1984 exile edition of Milan Šimečka’s Restoration of Order (Obnovění pořádku), one of my most treasured sources of information about life during the 1970s normalization period.

Monumental fresco in the prelature

Back to Santini. This time Santini made his mark in the Church of the Assumption of Our Lady mostly with the massive organ lofts that were situated in front of a Gothic altar in the transept. He also worked on the naves. The feeling I got from the church was so uplifting. Literally, I found myself looking upwards but also mentally I found myself in a good mood, delighted by the Baroque decoration that enveloped the space. We also saw the prelature, which featured a monumental fresco celebrating the angelic bliss of the Cistercians. The fresco was bursting with energy, and I found myself embracing life to the fullest.

Lower Cemetery shaped as a human skull

Santini designed other structures for the town as well. We also saw the Lower Cemetery, which Santini shaped as a human skull with three chapels. It was constructed at a time when the plague was spreading throughout Europe. Because the plague never reached Žďár nad Sázavou, no one was ever buried there. I admired the design because it was so bold, so vivacious.

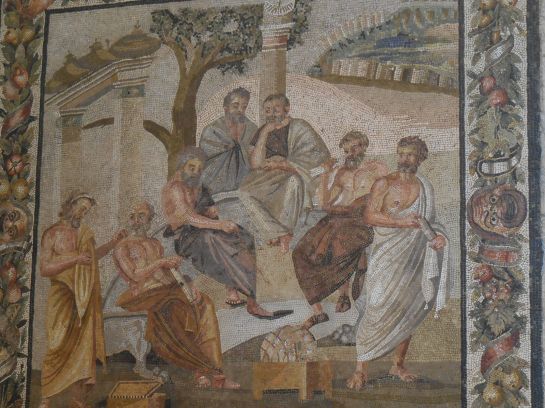

Perhaps Santini is best known for his last creation, the site we visited next – The Holy Shrine of St. John of Nepomuk on Green Mountain (Zelená hora), the area where Saint John of Nepomuk was allegedly raised, near the historical border of Bohemia and Moravia. I had been to this UNESCO World Heritage Site once previously, during a bitterly cold October afternoon, but I had been on my own and had not fully appreciated it.

Holy Shrine of St. John of Nepomuk, Zelená Hora

This time I was on a tour, and the guide explained lucidly about the geometric symbolism that Santini employed. I immediately saw the connection with Borromini’s radical Baroque, which Santini had forged into his own unique style. Unfortunately, although it was April, it was snowing, and I was only one of many participants not dressed warmly enough for the cold temperatures.

In 1719 Saint John of Nepomuk’s tomb was opened, and the tissue thought to be his tongue was found to be intact. Žďár nad Sázavou Abbot Václav Vejmluva wanted to celebrate this miracle and show how much he revered the saint, so Santini designed a church and cloister area with five chapels and five gates on the hill. The number five is of great importance in Santini’s plans. The ground plan was shaped like a five-pointed star. The number five represented the five wounds of Christ as well as Christ’s five fingers of blessing. It also stood for the five stars that, according to legend, appeared when the queen’s confessor John of Nepomuk died, drowned in the Vltava on the orders of King Wenceslas IV, allegedly for refusing to reveal the queen’s confessions to her husband. There are five altars in the church, too.

Zelená Hora

The construction of a church based on a circular form and the intersecting shapes fascinated me, but I was glad to be finally ushered inside, temporarily escaping from the foul weather. The design was so rational yet inventive at the same time. The place had a mystical quality, too. The nave of the small church was surrounded by four chapels and a chancel as well as five ante chapels. I looked upward and was captivated by the representation of a large, red tongue on the dome. The windows above the entrances in the lantern chapels took the form of tongues as well.

The main altar at the Holy Shrine of St. John of Nepomuk

The dome of the Holy Shrine of St. John of Nepomuk with a painting of a tongue

The main altar in the Holy Shrine of St. John of Nepomuk

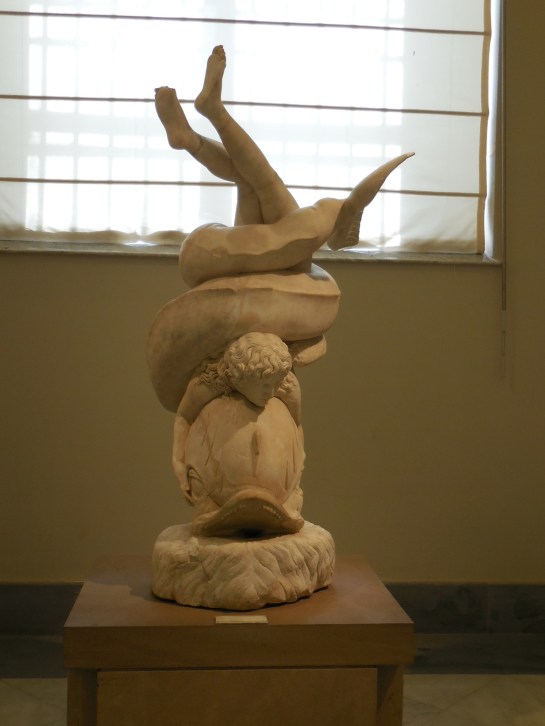

The main altar showed St. John of Nepomuk dramatically rising from a globe which boasted five eight-pointed Cistercian stars, standing for the five continents where Christianity ruled. Three angels were positioned around the globe, and another two opened a baldachin. The scene reminded me of a theatre performance, as if the angels were announcing that a play was about to begin. (During the Baroque period, theatre had flourished.)

Detail of the pulpit at Zelená Hora

The tongue-shaped windows at Zelená Hora

Before long it was time to brave the freezing weather again, and we made our way to the bus that would take us to the Church of Saints Peter and Paul in Horní Bobrová, built from 1714 to 1722. I noticed that the entrance portal took the form of a pentagon. Santini preserved only the nave of the originally Late Romanesque church that had originally stood there. He transformed the nave into a chancel with altar and added another nave. In doing so, he changed the entire orientation of the church.

Church of Saints Peter and Paul, Horní Bobrová

Interior of the Church of Saints Peter and Paul

The next church we saw was also in a village, this one called Zvole, which is officially in the Vysočina region. Santini redesigned the originally Gothic Parish Church of Saint Wenceslas so that the ground plan was shaped like a Greek cross. Construction took place from 1713 to 1717. The highlight of this church was its roof that sported a lantern topped with a crown, symbolizing the Czech patron saint. Santini extended the eastern section of the church, which featured a chancel. The church also had two rectangular towers.

The Parish Church of Saint Wenceslas, Zvole

Abbot Vejmluva had hired Santini for this project, and the architect paid homage by putting his patron’s initials, shaped as a W, along with a cross on the gable. Because the church was damaged by fire in 1740, most of the interior furnishings dated from the mid-18th century. The main altar hailed from 1770. Its painting showed a victorious Saint Wenceslas. The picture, hailing from the second half of the 17th century, was the work of the Czech Baroque master, Karel Škréta.

Detail of the pulpit in Zvole

Before checking into our hotel in Žďár nad Sázavou, we stopped in front of a pub at Ostrov nad Oslavou, which boasted a ground plan in the shape of the letter W, meant to honor Vejmluva, who had Santini build it. We then went to our hotel, an ugly, gray building with decent rooms and decent food in a quaint dining area.

Church of the Virgin Mary, Obyčtov

The next day began with a trip to Obyčtov, where Santini had arranged the ground plan of the Church of the Virgin Mary in the shape of a turtle, symbolizing the constancy of faith. The shapes of Santini’s structures continued to fascinate me. I was still enamored by the Lower Cemetery in the shape of a human skull and the geometric forms at the Holy Shrine of Saint John of Nepomuk on Green Mountain. Santini was able to make the church in Obyčtov so dynamic by giving it such a defining, bold shape. I had abhorred math as a youth, but I appreciated how Santini integrated geometrical forms into his designs. I reveled in the mathematical symbolism of Santini’s creations. We happened to have a church organist in our group, and he played the organ in Obyčtov. With the notes resonating throughout the Baroque structure, I had an even greater appreciation of Santini’s architecture.

Pulpit at the Church of the Virgin Mary, Obyčtov

I had visited Rajhrad Monastery about six years earlier, when I had devoted my time there to the Museum of Moravian Literature and an exhibition on the life and work of my favorite Czech writer, Bohumil Hrabal. This time we visited the Church of Saints Peter and Paul and the monastery interiors apart from the museum.

Church of Saints Peter and Paul in Rajhrad

The monastery was established back in 1048 and is the oldest existing monastery in Moravia. Originally Romanesque in style, the monastery was rebuilt in Baroque style in the 18th century, thanks to Santini. It remained functional during Emperor Joseph II’s reign. It experienced dark days under the Communist regime. In 1950 the Communists took it over, and the monks were placed in detention camps. The army took over the complex. After the Velvet Revolution the monastery was in a shambles.

The monastery was situated on swamp land, and Santini solved this problem just as he had at the west Bohemian monastery of Plasy. He placed the building on wooden piles and grates. He flooded the oak wood with water so that they would not rot. A small pond nearby had formed a sort of water reservoir, a place where rainwater could drain and a place where the underground water could level out. Unfortunately, in the latter part of the 20th century, the pond was filled up, and some of the piles began to rot, which did not fare well for the walls. Concrete has been used to fill in the foundations.

Interior of the Church of Saints Peter and Paul

The space that fascinated me most was the third largest monastery library in the country. The illuminated manuscripts on display were dazzling. The oldest hailed from the ninth or 10th century and dealt with the lives of martyrs. In awe, I gaped at The Bible of Kralice. It was the first complete translation of the Bible from original languages into Czech, dating from 1579. The Bible of Venice was on display, too. It was the first Czech printed bible published abroad, in Venice, during 1506. Some shelves only contained Bibles, but others held books about theology, history, medicine and mathematics, for example. There were even some works of fiction in the library. The books were written in Latin, German, English, French and Hebrew, for instance. I took a few moments to gaze at the Pergameon manuscript from the 13th century.

The stunning fresco on the ceiling celebrated the Benedictine Order. The fresco also included portrayals of musical instruments. There was illusive painting of three statues in the room, too. What really caught my attention, though, was the large globe. It took a monk 16 years to create the globe that had been finished in 1876. He had drawn the entire world on it by hand. There were various clock mechanisms on display, and clocks told the time at noon in various towns in the world, such as Tokyo, Melbourne and Honolulu. The huge, white books in one corner hid a staircase that went up to the gallery.

The Church of Saints Peter and Paul used decoration of artificial marble, which was more expensive and lavish than natural marble. This space was just one more example of Santini using light in a dynamic way so that the visitor is drawn toward the main altar. Yet the light affects each space in a different way. Each section has its own intensity, giving the church a unique character.

The ceiling frescoes astounded me. They were so dynamically and dramatically Baroque. This was an altogether different Baroque than we had witnessed the previous day. This Baroque was livelier, jumping at the viewer, more intense, practically rippling with tension. The style of Baroque was more open than the rather closed, Czech style we had seen the previous day because Rajhrad was closer to Vienna, where there was a different understanding of Baroque. The feeling in Rajhrad was uplifting. Looking up at the ceiling frescoes, I felt as if I could soar into heaven.

The main altarpiece in Jedovnice

Taking a break from Santini, we visited two modern churches. The first one was in the village of Jedovnice, which was first mentioned in writing during 1269. A church had stood in the village since the 13th century. The Church of Saints Peter and Paul was built from 1783 to 1785, though the foundations of the tower go back to 1681. However, a fire destroyed most of the town in 1822. During 1873 a Neo-Gothic main altar was installed with a painting of the two saints. From the outside it looked like a typical village church. The interior, though, was a different story.

Closeup of the main altar

In 1963 the main altar was dismantled, and in its place appeared a modern work of art by Mikuláš Medek, a prominent Czech painter during the second half of the 20th century, and Jan Koblasa, a Czech sculptor, painter, poet and musician who also had decorated the presbytery. The balustrade on the organ loft was designed by one of my favorite contemporary sculptors, Karel Nepraš, who had a very unconventional style. I had always been intrigued by Nepraš’ sculptures made of wire, pipes or metal objects.

A Gothic statue in the modern church at Jedovnice

The main altar picture showed Christ’s cross painted in blue, which stood for hope. The gold circle in the middle of the Cross meant that the value of the cross is inside; a person first must comprehend God’s suffering before he or she is able to have hope. The powerful picture had a mystical quality.

The modern windows in the nave got my attention. For example, one showed the death of Saint Paul, showing how the execution sword becomes a path to new life. The window symbolizing the death of Saint Peter was decorated with tears in the background to show Peter’s regret at having denied Christ three times. I also noticed that the cross was upside down, the way Peter was crucified. The white, modern pulpit startled me. The Gothic Madonna had been brought from a church destroyed during the 15th century Hussite wars and seemed very out-of-place with the abstract adornment.

The Chapel of Saint Joseph in Senatářov

In Senatářov we saw the modern Chapel of Saint Joseph, which had opened in 1971. A chapel had stood in the village dating back to 1855. In 1891 there was a 2-meter high stone cross and a stone statue of Saint Joseph in the chapel. The Nazi Occupation was a horrific time for Senatářov, when the inhabitants were forced to move to 85 other villages. That’s when it was decided that, if the people ever return to their hometown, they would erect a new chapel. And that is what they did – from 1969 to 1971. During the more liberal time of the Prague Spring in 1968, the community was able to get permission to build the chapel. However, the Communists then forbid them from consecrating the church. It was not consecrated until 1991. The interior furnishings include an abstract work of the Last Supper and another fresh perspective on the Stations of the Cross. The light fell dramatically on the main altar in the church as light played a dynamic role in the interior.

The main altarpiece in Senatářov

While I admired what artists were trying to do by utilizing modern decoration, the style did not work for me personally. I much preferred a Gothic or Baroque church to a modern, abstract style. I liked churches that spoke of a historical past, where I could see and feel the connections with the past traditions. The modern style left me with a sort of emptiness. I felt that I had nothing to relate to. I needed to feel the weight of centuries past, to feel that for so many centuries people had stepped into that space and prayed and cried and hoped.

The Chapel of Saint Joseph, Senatářov

The last place on our list was certainly one of the most impressive: The Pilgrimage Church of the Virgin Mary in Křtiny, near Brno, the capital of Moravia. This time Santini used the shape of a Greek cross as the ground plan for the nave. A central dome and frontal tower were two other features of the architectural gem. The cupola measured 54 meters in height, and the tower was 73 meters high. Two rows of windows – there are more than 30 windows in total – brought light into the church. The lower windows were rectangular while the upper ones were smaller, oval in shape.

The Pilgrimage Church of the Virgin Mary in Křtiny

I was overwhelmed by the fresco decoration. The natural light and the Baroque frescoes gave the place an airy feeling. The fresco in the main cupola celebrated the Virgin Mary, who was accompanied by saints. The oratory above the main entrance had stunning fresco adornment, too. It showed angels with musical instruments celebrating the Virgin Mary.

The Madonna of Křtiny

The main altar was breathtaking with the life-size Gothic statue of the Madonna of Křtiny or Virgin Mary of Grace, the patron saint of Moravia. The statue hailed from the end of the 13th century. Made from marlstone, it is polychrome and partially gilded. The Madonna stood on a black marble pedestal. The Virgin Mary gripped a scepter while Jesus held an apple. A golden half-moon also decorated the statue. Golden sunrays surrounded it. Some of the paintings decorating the interior were by Ignatius Rabb, one of the premier Czech Baroque artists of the 18th century. I was also impressed with Saint Anne’s Chapel and the cloister with its votive paintings. There was a carillon, too, and we listened to the bells’ tranquil melodies.

Then we made our way back to Prague. The trip had been exhilarating. I had visited many new places and now appreciated Santini’s work, thanks to an expert guide. I had found The Holy Shrine of St. John Nepomuk and the Church of the Assumption and of St. John the Baptist to be the most impressive. I loved Green Mountain for its mathematical symbolism. The theatricality of the main altarpiece also had grabbed my attention. In the church at Sedlec, I loved the way light imbued the church with a mystical quality. I loved the way light defined the space. And the ceiling network of vaults – it was overwhelming, almost too much to take in.

The trip had more than lived up to my expectations. I was eager to see the west Bohemian sites that Santini had designed – hopefully, next year a tour would be offered. I also had a better appreciation of architecture in general. And, of course, the Baroque Gothic style would always be dear to my heart.

Church of the Assumption of Our Lady, Žďár nad Sázavou

Tracy A. Burns is a writer, proofreader and editor in Prague.