A street in Bologna

Note: No photos were allowed to be taken in the Basilica of Saint Petronio and in the Oratory of St. Cecilia.

Before traveling to Bologna, I studied the town’s history and was amazed that so many cultures had made such significant imprints on the city. The Romans, the Etruscans, the Byzantines, the Goths, the Gauls, the Celts, the Franks, the Lombards– they all played major roles in the town’s early history. It fascinated me that Bologna’s history dated all the way back to the Bronze Age of 1200 BC. During 9 BC, as a village called Felsina, it made a name for itself in ceramics and bronze objects. The town was under Etruscan rule during the 6th century BC, then the Gauls took over, followed by the Celts. The Romans defeated the Celts in 202 BC. Under Roman leadership the town was transformed into a wealthy and important Roman colony called Bononia.

After dark days of Barbarian raids, the Byzantines took charge in 553 BC and spread Christianity throughout their realm. The Goths and Longobards also made appearances in later centuries. Charlemagne conquered the town, and the Franks became a major influence. When Charlemagne gave the town to the Church, conflict broke out among the residents who wanted the Church to be in charge and those who wanted the town to be part of the Italian Kingdom. The conflict tied to Church versus State under Charlemagne foreshadowed the many centuries of warfare between the pro-Church Guelphs and pro-Emperor Weilblingen and deeply divided cities and territories. Bologna did, in fact, become part of the Italian Kingdom in 898 AD.

The Asinelli tower is the highest in the city at 98 meters.

During the 11th century the first university in Europe was established in Bologna. After some civil unrest, the Church took over in the 13th century, and Bologna became very wealthy. By the end of that century, Bologna had the fifth largest population in Europe. During the 12th and 13th centuries, the most prosperous citizens competed by building towers as lookouts and defense structures in case war broke out. Except for the 1795 to 1815 rule of Napoleon, Bologna was part of the Papal State from 1506 to 1860.

The 19th century was fraught with battles, though. Bologna belonged to the Kingdom of Sardinia and then became part of the Kingdom of Italy. At the end of World War I, the town found itself in dire straits with many unemployed and homeless people. The situation during World War II was no better, and the Nazis took over in 1943, the year that bombs fell on the town twice. In April of 1945, Bologna was liberated by the sole partisan unit in Italy that was officially suited and supplied with arms by the Allies. Now nicknamed La Saggia (the Wise One), La Grassa (the Fat One) and La Rossa (the Red One), Bologna is the capital of the Emilia Romagna region with 410, 000 residents.

The statue of Neptune is a symbol of the city.

I knew the city was most famous for its food, its university and its towers as well as its red brickwork. Still, I did not have great expectations of Bologna. I thought it would be an intriguing town, but I was most excited about the trip to Ravenna on the itinerary with this five-day tour operated by the Prague-based arsviva travel agency.

I was amazed by the romantic porticos – they spread 59 kilometers and gave the town a unique flavor. And then there were the towers. I stretched my neck and gazed in awe at the imposing structures. The most famous towers in Bologna, the Asinelli (98 meters tall) and the Garisenda (48 meters tall, formerly 61 meters) had been constructed in 1109 and 1119 respectively as two noble families competed to see who could build the highest tower. Garisenda is the “leaning tower” of Bologna with a slant of 3.25 meters. While more than 100 towers were built in Bologna during the 12th and 13th centuries, less than 20 have survived.

But while Bologna represents food, towers and porticos to some, to me the highlights of the city were the magnificent churches. To be sure, Bologna ranks as one of the most romantic and unique cities I have ever visited. Bologna was mystical and mysterious. Bologna was magical.

The exterior of the Basilica of Saint Petronio

One of the most significant landmarks in the town and one of the most impressive sights for me was the Basilica of Saint Petronio. Built to honor a 5th century bishop of Bologna, the Basilica of Saint Petronio is the largest church in Bologna and the 15th largest in the world at 132 meters long and 66 meters wide. Often depicted holding a model of this very church, Saint Petronio was important in part because he built the Church of Santo Stefano, inspired by his travels to religious sites in Jerusalem.

To stand inside the solemn structure is awe-inspiring and overwhelming. To think that the foundation stone was laid way back in 1390 (though the structure was not completed until 1670) was mind-boggling. Entering the church, I felt as if I had been transported back centuries. It consisted of 22 chapels, 11 on each side. Four carved crosses were supposedly built by Saint Petronio at the four cardinal points of the city. The three-aisled Gothic interior was supported by 10 pillars. The basilica was shaped as a huge cross. The largest sundial in the world, measuring 66.8 meters and hailing from 1655, was inlaid on the floor.

Postcard of Chapel of the Magi, showing the Journeys of the Magi, fresco by Giovanni da Modena, 1410

What captivated me the most was the fourth chapel on the left, The Chapel of the Magi. I stared at the Gothic altarpiece with the 27 exquisitely carved, wooden, painted figures, and I was awestruck. Just think of how much work it took to so meticulously carve and paint those figures! I could not peel my eyes away from it. When I finally did, I saw something else magnificent. On the left-hand side wall near the top Heaven was depicted, with the crowned Virgin Mary surrounded by saints.

Underneath that idyllic rendition was Hell – right out of Dante’s Divine Comedy. Lucifer, resembling a gigantic monster, was devouring one of the three traitors – though I could not tell if it was Brutus, Cassius or Judas, as described in the 34th canto. The image was much more than grotesque. It was terrifying. For me it represented all the evil in the world. It brought to mind criminal acts, betrayal, hatred. The travels of the Magi were also pictured along with scenes from Saint Petronio’s life. The stained glass in the chapel hailed from the 15th century.

Postcard of the Chapel of the Magi with Lucifer as the central figure in Hell

The basilica held other delights, too. The frescoes of the Chapel of Saint Abbondio dated from the 15th century. I tried to imagine the festive atmosphere when Charles V was crowned Emperor in this chapel by Pope Clement VII during 1530. What had the invitees worn? What had they talked about while waiting for the coronation to begin? Where had they gone after the historic event?

The second chapel on the left was dedicated to Saint Petronio, and his skull was kept in a silver shrine. The head of this patron saint of Bologna had only been in this basilica since 2000; before that it had been housed in the Basilica of Santo Stefano. Marbles, bronzes, statues and frescoes also decorated the holy space.

Postcard of the Chapel of the Magi, Journeys of the Magi, fresco by Giovanni da Modena, 1410

The Chapel of Saint Ivo featured two intriguing clocks. The clock on the left-hand side showed the real time in Bologna. The one on the right, though, depicted the time as seen on Italian clocks from 1857 to 1893, when time started to be counted in the evening. The huge image of Saint Christopher was imposing, too.

The seventh chapel on the left, the Chapel of Saint James, featured a 15th century altarpiece but was perhaps best known for containing the remains of Napoleon’s sister, Elisa Bonaparte, who died in 1845, and those of her husband, a member of the Corsican nobility named Prince Felix Baciocchi, who attained military and political prominence. Elisa served as Princess of Lucca and Piombino, Grand Duchess of Tuscany and Countess of Compignano. She was a patron of the arts who set up academic institutions, had a new hospital built in Piombino, worked with charities and organized free medical help for the poor.

Postcard of Chapel of the Magi, The Inferno, frescoes by Giovanni da Modena, 1410

The 15th chapel near the left wall was where Pope Clement VIII conducted mass in 1598 before he walked barefoot to greet his followers in the main square, the Piazza Maggiore. The Our Lady of Peace Chapel was connected with an intriguing story. An irate soldier who lost much money while gambling had struck the Madonna in this chapel with his sword, and the sculpture came closing to falling on his head. He was sentenced to death but later pardoned because he had prayed so fervently. There was a 15th century figure of the soldier near the left wall.

All this stunning art work left me dizzy with wonder as I gaped at the interior, not wanting to leave, feeling compelled to stay there forever just gazing at the various chapels, noticing more and more astounding details.

Basilica of Santo Stefano

I was also fascinated by the Basilica di Santo Stefano, also called “The Seven Churches,” though now there are only four. It intrigued me so much because so many cultures had played a role in its development over the centuries – Roman, ancient Christian, Byzantine, Lombard, Frank, Ottonian – people of all these cultures had once gathered at the complex that goes back at least 2,000 years.

Founded in the early years of 5 AD by Petronio, the bishop of Bologna who would be buried there and would become canonized. It was built on the site of a first century AD pagan temple dedicated to Isis which was built over a spring. Petronio’s visit to Jerusalem even inspired him to create the only copy in the world of the Holy Sepulchre of Christ. In fact, this complex used to be called “Jerusalem.” Now the Oliveitani Order lives there. Before that Benedictine monks and Lombards had been among the owners of Santo Stefano.

Church of the Crucifix

I entered the Church of the Crucifix and admired its austere Romanesque style. Once a Lombard church, this holy place has no aisles. A striking papier-mâché Pietà scene stood out on the right side. Stairs led to the presbytery. A yellow marble altar and a fresco of the Crucifixion decorated the church, too.

More stunning decoration at the Basilica of Santo Stefano

What I loved about the crypt were the various styles of the columns’ capitals that divided the nave and aisles. I saw cubic, Frank and Tuscan styles of capitals. A column with no capitals was connected to an intriguing story. Supposedly, it was forged from two stones that Petronio had taken from Jerusalem. The remains of Saints Vitalis and Agricola, Bologna’s first martyrs from 304 AD, were kept in the crypt, too. Christian Agricola had convinced his slave Vitalis also to take up the Christian faith.

Copy of the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem, Basilica of the Holy Sepulchre

Next came the outstanding Basilica of the Holy Sepulchre. This was the part that began as a pagan temple, constructed on the site of a spring. I tried to imagine all the people who had entered this place since 1 AD. What had they been thinking about? How had they lived? What had their daily life been like? What were the different kinds of services held here? The model of the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem astounded me. Just think: I was looking at the only copy of this holy structure in the world. It was breathtaking. Dimly lit, the space looked mystical and mysterious as if it held many secrets that would never be revealed. Saint Petronio’s remains were under a grill in the center of the model sepulchre, but, as I mentioned earlier, his head was housed in the Chapel of San Petronio.

The ceiling at the Basilica of Santo Stefano

The Basilica of Saint Vitalis and Saint Agricola was simple and austere in its Romanesque Lombard appearance with one nave and two aisles. I saw remnants of mosaics and frescoes. I noticed figures of lions and deer decorating Saint Agricola’s sarcophagus. Legend says that the cross in this church was the same one on which Saint Agricola was crucified. Again, the various styles of capitals captivated me. I saw Ionic, Byzantine and Frank capitals. I could not stop thinking that so many cultures had worshipped in this one space.

Marble Lombard basin in Pilate’s Courtyard

Referring to Pilate’s washing his hands of Christ’s blood as he declared Christ innocent, Pilate’s Courtyard included Romanesque Lombard style arcades and a marble Lombard basin dating from 730 to 740 AD on a 16th century pedestal in the center. While the arcaded space showed off chapels and tombstones, there was a unique object there as well – a 14th century stone rooster that symbolized Saint Peter’s three-time denial of Christ’s existence during the night of his arrest and interrogation. (People at the bonfire recognized Saint Peter as one of the apostles, but he pretended he did not know Christ.)

The Adoration of the Magi in the Martyrium Church

The Martyrium Church, named after the areas where martyrs were buried, had been restored in the Frank style of the 17th century. It consisted of a nave and double aisles with columns. There were 14th and 15th century frescoes in the apses. I particularly liked the sculptural grouping of the Adoration of the Magi, with its enchanting, bright colors, such as deep red. And it always amazed me to see remnants of Romanesque architecture. I was not disappointed.

The Basilica of Santo Stefano boasts breathtaking artworks.

There was a cloister adjacent to the basilica. Supposedly, Dante had been inspired by the animal heads of human faces with scornful, ridiculing expressions. The cloister consisted of two basic sections, the upper part, built at the end of the 17th century and the lower part, constructed around 1000. It was fascinating to see these two greatly different styles side-by-side. I felt as if the human faces with animal characteristics were trying to insult me, as if they were laughing at me. They certainly gave me an uncomfortable feeling.

I was dizzy with delight as I left the basilica. Each church was unique, each church told its own story. I could not believe that I had walked on the same ground that dated back to 1 AD in a structure hailing from 5 AD. I could have spent hours walking through these spaces, taking in the atmosphere, soaking up the ancient history.

The ceiling of St. Dominic’s Basilica

The three-aisled St. Dominic’s Basilica ranked as another highlight of my time in Bologna. Founded in the 13th century, this holy place housed the marble Ark of Saint Dominic, who founded the Dominican Order and died in 1221 in Bologna, when the basilica had been a church. I could hardly believe that I was looking at the 1264 work of master artist Nicola Pisano. I had admired Pisano’s craftsmanship of the pulpit at the baptistery in Pisa and the pulpit at Siena’s cathedral.

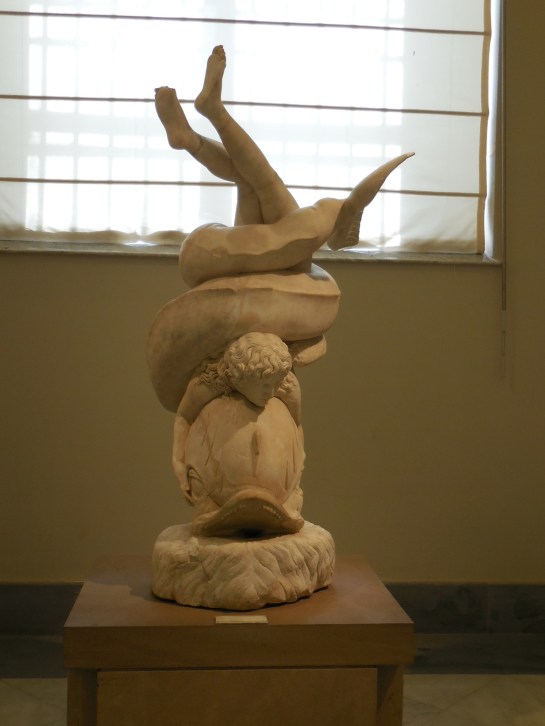

The angel carved by Michelangelo on St. Dominic’s sarcophagus

Additions were made from 1469 to 1473, and Michelangelo contributed to the decoration. I was fascinated by the curly-haired angel designed by Michelangelo, who also created the statues of Saint Petronius and Saint Proloco. That angel seemed so lively, as if he could step off the sarcophagus and dance through the aisles. I also admired the gold and silver enameled panels on the reliquary that contained St. Dominic’s head. The statues in niches flanking the reliquary were impressive, too. The ornate spire that crowned the Ark was another delight. Two putti and four dolphins held the candelabrum. The four Evangelists also made appearances.

Saint Dominic’s sarcophagus

The Oratory of St. Cecilia also caught my undivided attention. The St. Cecilia Church was first mentioned in writing during 1267, and it was moved to its present location in 1359 by Augustinian hermits. Connected to the Church of St. James Major, a 15th century stunning Renaissance structure, the Oratory of St. Cecilia featured paintings from 1505-1506. They told the story of Saint Cecilia’s life.

Postcard of the Oratory of St. Cecilia, St. Cecilia’s Trial, 1505-1506

The story of Saint Cecilia was intriguing. On her wedding night St. Cecilia told her pagan husband Valerian that an angel would protect her if he tried to take away her virginity. She convinced him to become a Christian and before long he was baptized by Pope St. Urbano. His brother Tiburzio also converted, and together they spread Christianity throughout the land. They were beheaded for their beliefs. Even when St. Cecilia was tortured, she was not injured. She managed to give all her belongings to the poor before she was killed in 230 AD. Interestingly, although St. Cecilia is considered to be the patron of music, there were no references to that art in these renditions.

Postcard of the Oratory of St. Cecilia, St. Cecilia’s Charity from 1505-1506

I noticed the classicized angel clad in a fluttering blue drapery in the fourth scene, “Angel bearing the Crowns of Martyrdom” and the gruesome beheading in the “Martyrdom of St. Valerian and St. Tiberius.” I felt the sense of desperation of the naked woman with an emaciated child waiting for alms from St. Cecilia as St. Cecilia gave money to a grateful, kneeling man. I noticed how in “St. Cecilia’s Burial” the bright red garment she was clad in contrasted with the white sheet that held her corpse.

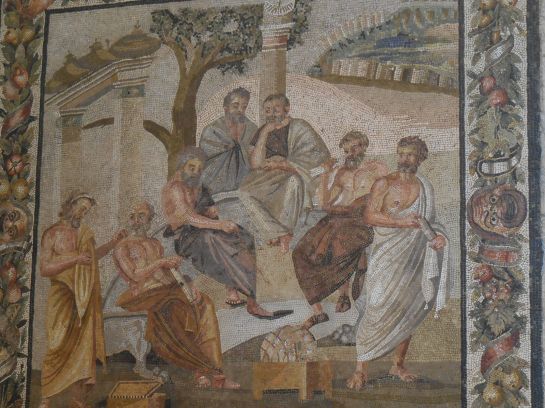

Fascinating medieval art at Bologna’s National Gallery

A museum addict, I also enjoyed my time at the Museo Civico Archeologico, perusing its prehistoric, Etruscan, Roman and Egyptian collections. My favorite museum, though, was the National Picture Gallery and its plethora of art from the Middle Ages. The museum certainly held an impressive collection of 14th century works. When the Church was losing power in Bologna, many of these masterpieces were moved from the churches to the picture gallery. When Napoleon’s reign ended, the museum acquired even more artworks. Its 29 halls were filled with fascinating works by Nicola Pisano, Tintoretto, Titian, the Carraccis and Il Perugino, to name a few. Then there was Raphael with his Ecstasy of St. Cecilia. In addition to medieval art, other periods were covered, such as Mannerism and Baroque.

The National Picture Gallery was full of medieval delights.

Bologna definitely meant towers, porticos and food. Bologna was the delicious Pizza Margherita – the best I had ever had – at a bar I frequented in the center of town. I loved the bars frequented by locals who came in for cappuccinos or shots of espresso, downing them as they stood at the counter and chatted with the bartender.

Yet most of all, Bologna to me will always be churches and the many cultures that they represented. Bologna was romantic and picturesque, but it was first and foremost mystical and mysterious. The churches seemed to contain so many secrets.

National Picture Gallery, Bologna

I had stood in what had been a first century temple to Isis and a church dating back to the 5 AD. I had seen a copy of the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem. I had marveled at the exquisite carving of the figures on the Gothic altarpiece in the Chapel of the Magi and at the paintings of Heaven and Hell that adorned it. I had been captivated by St. Dominic’s Ark in the basilica, by the exquisite carving of the statuary and other decorations on the sarcophagus. The story of St. Cecilia fascinated me. The medieval art at the National Picture Gallery left me in awe.

However, most of all, for me Bologna was hope and faith. The city reminded me of the importance of having faith in the world, of having faith in myself. When it was time to say goodbye to Bologna, I left this city with a new and more positive perspective on life.

More stunning medieval art at Bologna’s National Picture Gallery

Tracy A. Burns is a writer, proofreader and editor in Prague.