This permanent exhibition at the Gallery of Modern Art in Hradec Králové showcases the works of some of the most influential Czech artists of the 20th century. I liked the fact that the works were organized by person with commentary about the artists’ backgrounds and styles. I will highlight the creations that most influenced me, although all the painters and sculptors are important.

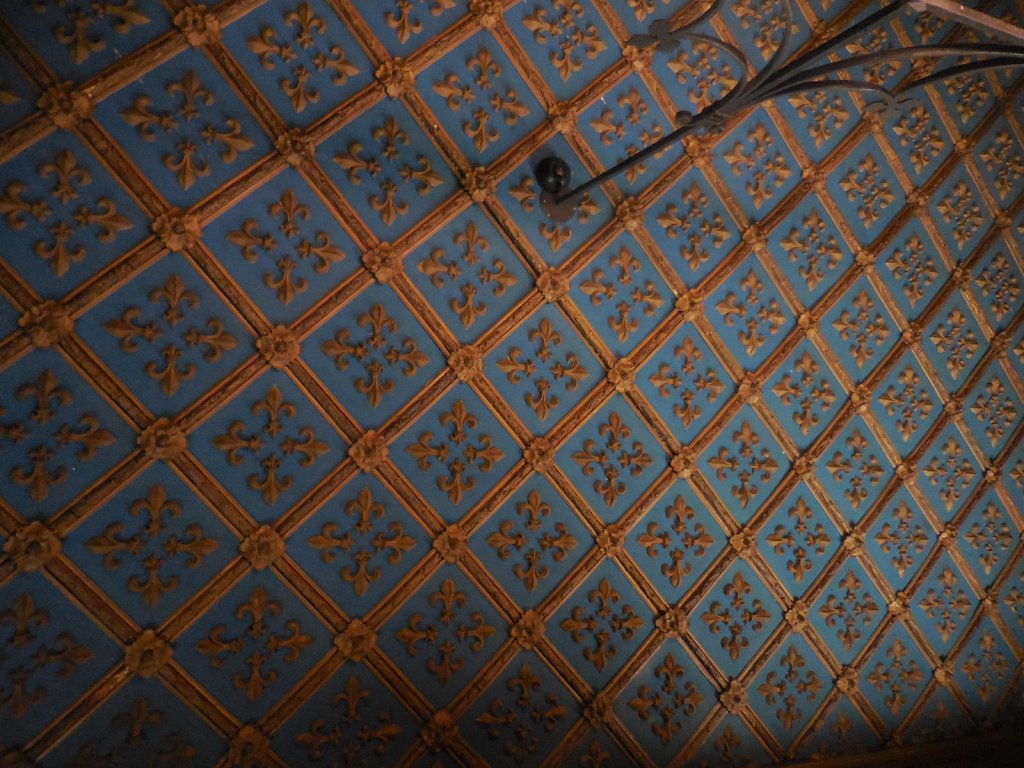

First, about the building housing the Gallery of Modern Art: Like many edifices in Hradec Králové, the museum is an architectural gem. Facing the town’s main square, the building that was completed in 1912 by Osvald Polívka is impressive with two statues flanking the façade. These sculptures were made by Ladislav Šaloun in 1908 and show allegories of commerce and the harvest. Reliefs of atlases with dogs at their feet also make up the external ornamentation. Polívka’s Art Nouveau designs can be found in Prague’s Municipal House, which he decorated from 1905 to 1912. I tell everyone coming to Prague to tour the Art Nouveau Municipal House, as it is certain to be a highlight of any visit. Šaloun created the statue of Jan Hus that dominates Prague’s Old Town Square.

Several banks were housed in this building before and during the First Republic. For many years under Communism, the Cotton Industry Association and an agricultural company called the place home. Renovations took place in the late 1960s. In 1987, the totalitarian regime transformed the building into the Museum of Revolutionary Traditions. This totalitarian exhibition was closed after the 1989 Velvet Revolution that freed Czechoslovakia from Communist control.

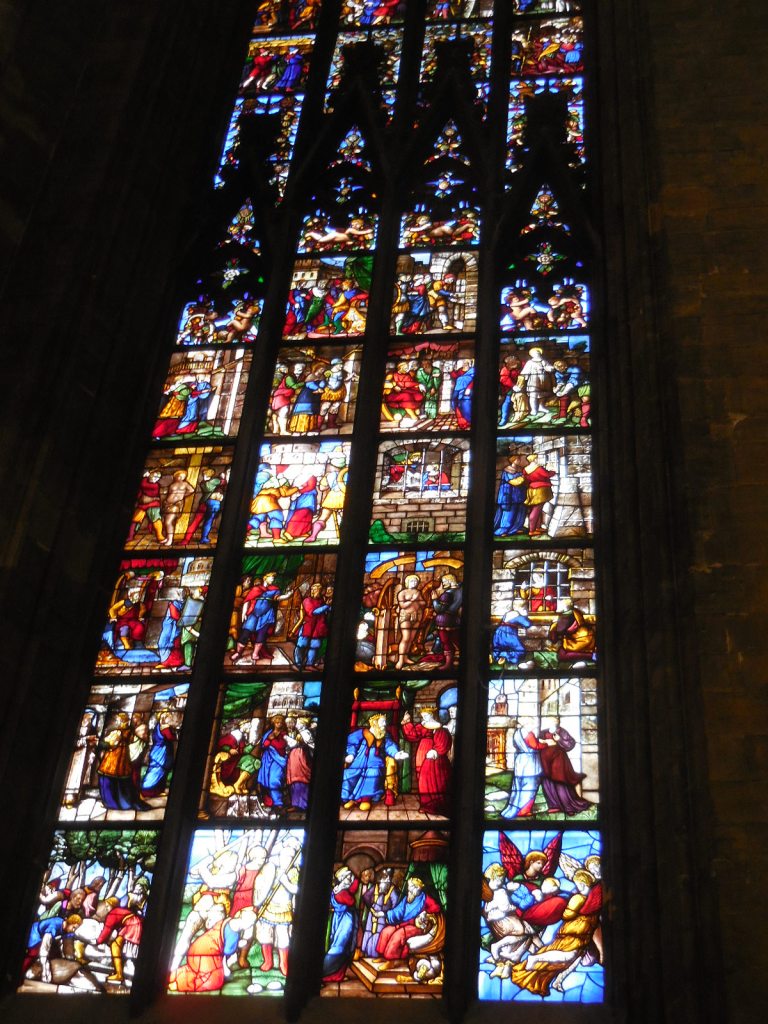

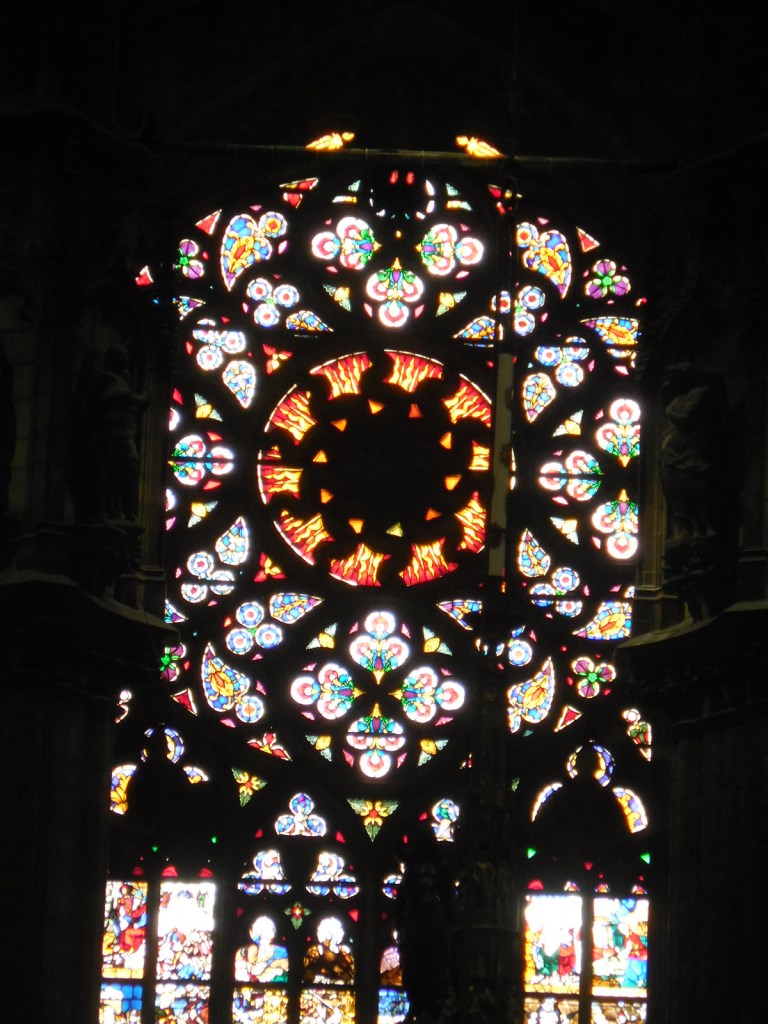

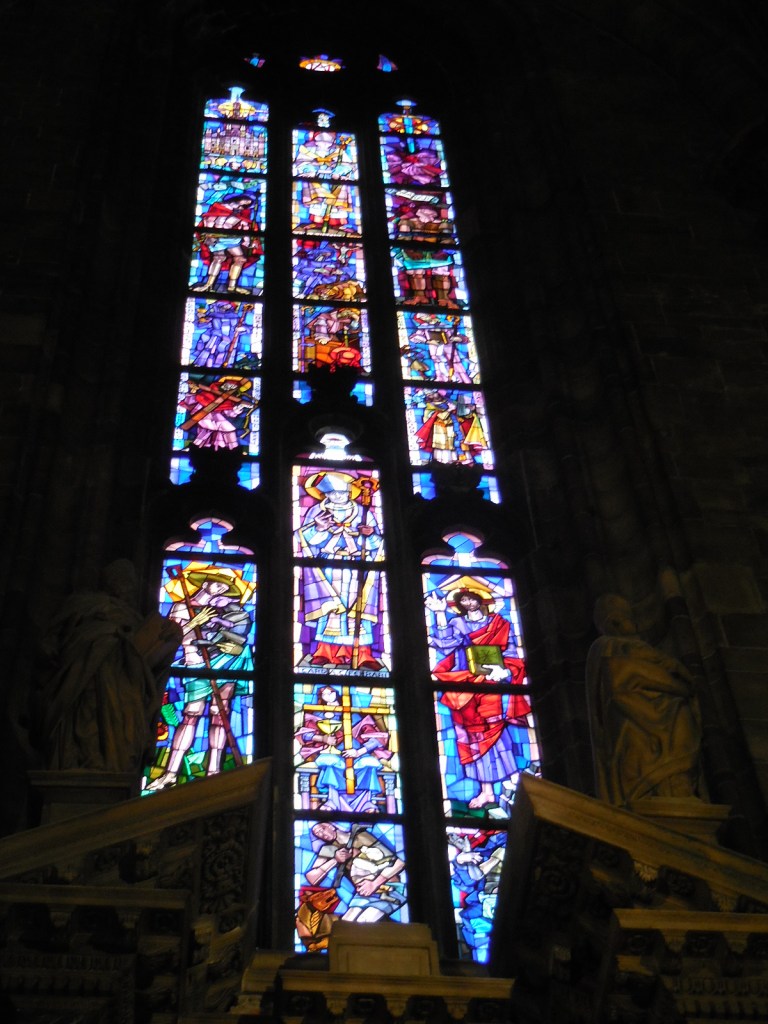

In 1990, the Gallery of Modern Art took up residence there. From 2014 to 2016, both the interior and exterior underwent a vast renovation. A walkway was formed around the central atrium, for example. The interior boasts geometric shapes, floral designs and Art Nouveau-styled adornment of garlands and cherubs. I especially liked the stained glass window decoration.

Here are some of my favorite artists represented in this exhibition:

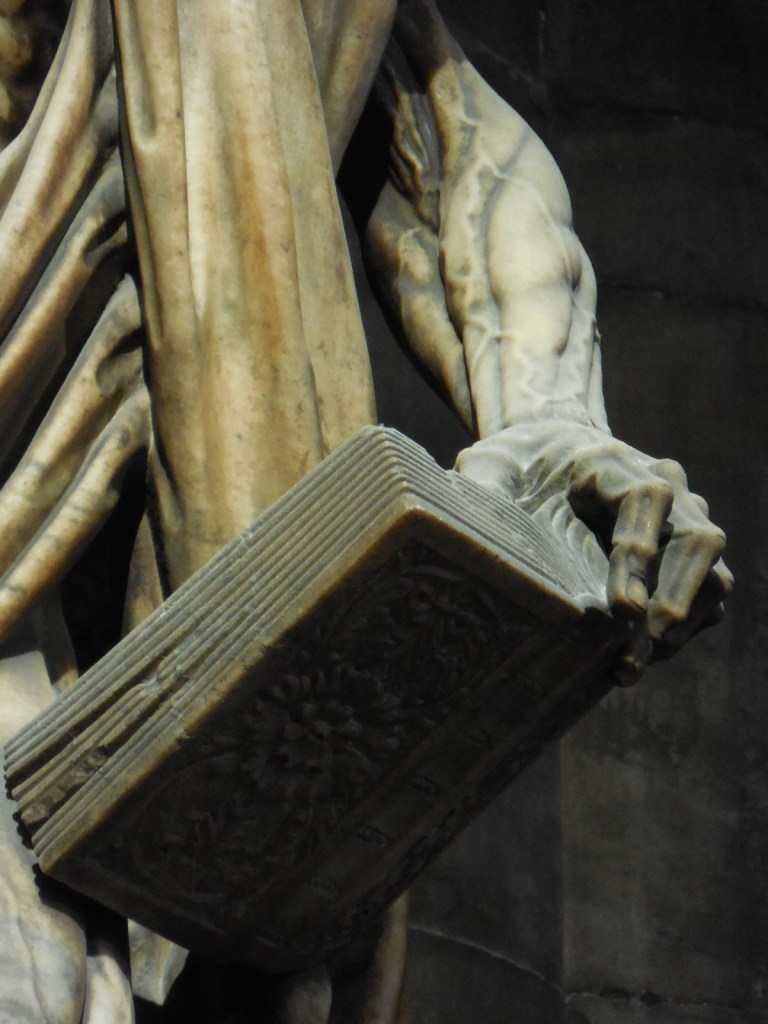

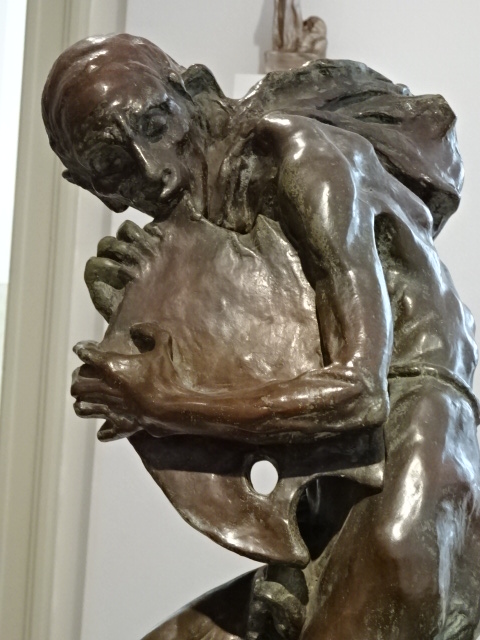

Fate of the Artist, 1909

Quido Kocián

The expressive sculpture of Quido Kocián was influenced by symbolism and Art Nouveau. I love how he was able to express basic emotions like love and suffering. I went to a superb exhibition of his work about 15 years ago on Husova Street in Prague. In some statues I could see the turmoil and anguish of the persons depicted. Other sculptures triggered feelings of happiness and fulfillment. Kocián had a knack for depicting various psychological states and the depths of the human soul. He studied under legendary artist Josef Václav Myslbek but wound up rebelling against Myslbek’s traditional style, opting for expressiveness instead. Kocián’s works were not fully appreciated in the Czech art history sphere for a long time.

Ladislav Zívr

Surgeon, 1961

A member of the artist Group 42, Zívr focused on everyday life, a feature that is dear to me in all art forms. Inspired by Cubism and the creations of Otto Gutfreund, he made sculptures that have machine-like qualities as well as human traits. He had a penchant for surrealism. After the world wars, Zívr was influenced by nature, and his works portrayed strong symbolism. I liked the way he was able to express a person’s soul through primitive forms.

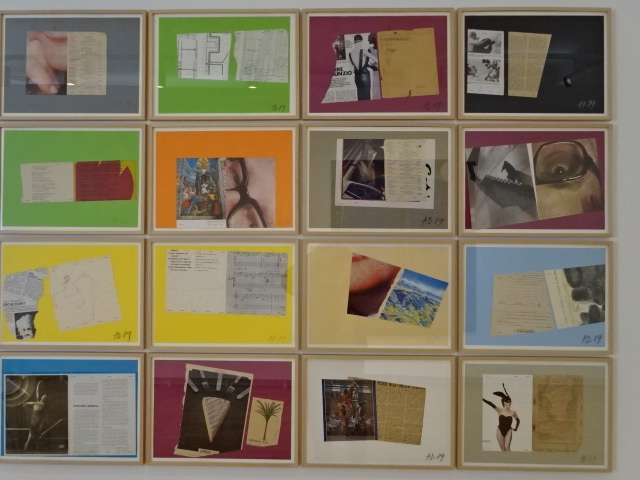

Jiří Kolář

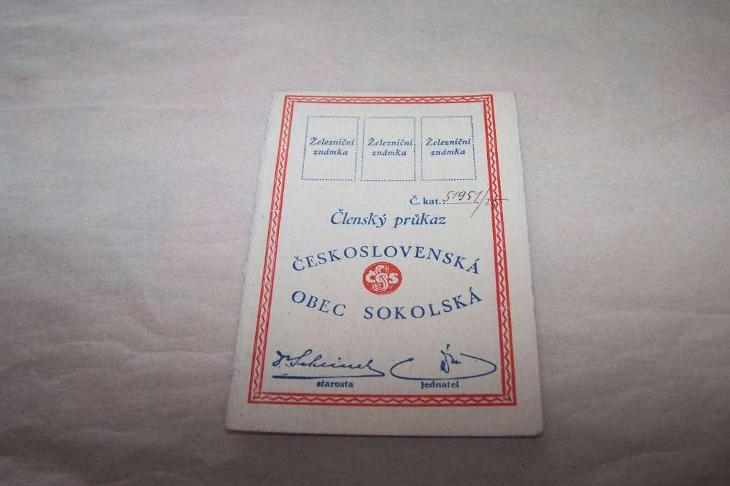

I had been to a large exhibition of Kolář’s works in Prague’s Kinský Palace some years ago and was very familiar with his collages that included cut out images and words from publications. (See my article about the exhibition in a much earlier post called Jiří Kolář Exhibition Diary) He was a poet and prose writer as well as a fierce critic of Communism. Kolář emigrated to Paris in 1979. He often used phrases from books or created his own poems in his collages. His works lingered on the border of the dream realm and reality, a trait I found very intriguing. A staunch supporter of democracy, Kolář was also one of the first Czechs to sign Charter 77, a document written by dissidents to promote human rights in the normalization era of Communist Czechoslovakia. He played a major role in publishing literature banned by the regime. Kolář was also one of the founders of the influential Group 42.

Jaroslav Róna

Scene by the Fire, 1984

I know Róna’s sculptures well, but I was not familiar with his paintings. Róna designed the abstract Franz Kafka Monument in Prague’s Jewish Quarter, an important sculpture to see in the Jewish Town. He is, indeed, a man of many talents: He has also worked as a painter, illustrator, screenwriter, author of books, actor, singer and educator. His works have a certain dynamic energy. He has been inspired by the Expressionism style of Edvard Munch, Oskar Kokoschka, Max Beckmann, Egon Schiele and Pablo Picasso. A supporter of democracy, he drew brochures for the Velvet Revolution during 1989. Rona is also an avid traveler. His sculptures can be found at Prague Castle as well as on the island of Crete and in many other places.

Josef Váchal

Sacrifice, undated

I liked the mystical quality in Váchal’s works. He was a graphic designer, wood engraver, bookmaker, writer and painter who excelled in all those genres. Váchal was inspired by expressionism. His works featured symbolism, naturalism and Art Nouveau tendencies. A soldier during World War I, he fought in 12 battles. The Communist coup brought hard times for Váchal, who remained isolated after 1948. People did not show much interest in his work then. In the 1960s, he received some acclaim. Much later people recognized that Váchal had created some of the most significant works of Czech graphic design in the 20th century.

Augusta Nekolová

Four Seasons, 1914

Because Nekolová was female, she had limited educational opportunities during the 19th and early 20th century. She did, however, study unofficially under the prominent Czech artist, Jan Preisler. Nekolová worked as a painter, illustrator and graphic artist. She steered away from representations of modern life in her works. She was known for her landscapes and for her emphasis on motherhood. Nekolová strove to promote the national identity of the Slav nation. She developed a strong interest in folk culture. At the end of World War I, Nekolová was hospitalized. She died in 1919 at the age of 29.

Bohumil Kubišta

In the Kitchen, 1908

Café, 1910

A prominent avant-garde artist, Kubišta helped found the Expressionist group the Osma (The Eight). He was a painter, graphic designer and theoretician and is considered to be the founder of Czech modern painting. His works dealt with existential issues. Kubišta’s expressionism was inspired by Munch. He was also influenced by Braque and Picasso’s Cubism. Kubišta analyzed the works of Eugene Delacroix and Vincent Van Gogh. His works also contain elements of Futurism and Fauvism. Kubišta often explored themes dealing with modern technology and nature. While serving in the Austrian army during World War I, he won the distinguished Leopold Order. He died of the Spanish flu at the age of 34 in 1918.

Emil Filla

Dance of Salome, 1911

Hej hore háj, Folk Song, 1948

Along with Kubišta, Filla established the Osma group. He also was known for his writings about art theory. During his early artistic endeavors, he drew inspiration from Edvard Munch’s Expressionism. Later he took up Cubism, influenced by Picasso and Braque. He also was captivated by Baroque still lifes by Dutch painters. El Greco and his symbolism fascinated Filla. In the 1930s, he became enthralled with surrealism. His landscapes demonstrate his knowledge of Chinese calligraphy. My favorite trait in his paintings involves his use of a harmony of colors.

Repression (Anxiety) by Josef Wagner – temporary exhibition

I especially liked the exhibition’s pieces of art influenced by Expressionism and Cubism. The colors and shapes in Kubišta’s and Filla’s works caught my undivided attention. I was introduced to Nekolová’s art and intriguing background at this exhibition. I was fascinated how Quido Kocián captured the emotions of the human soul in his sculptures while Zívr concentrated on simple forms to create profound meaning. Kolář’s collages were a sort of visual poetry. Váchal and Róna’s creations displayed impressive energy.

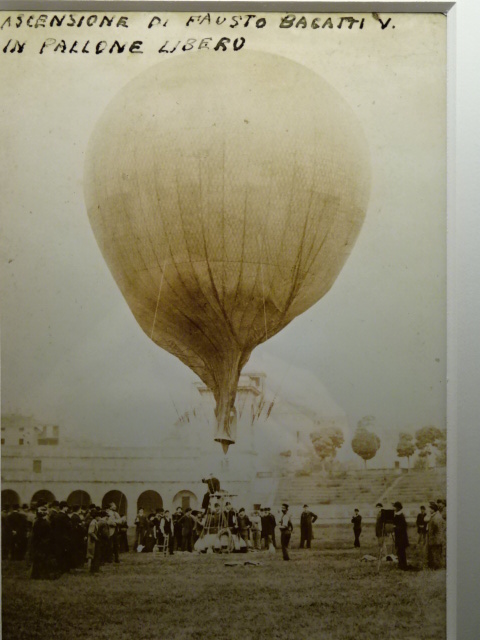

Moscow Diary, 1989 by Anna Daučíková

It was my first visit to Hradec Králové, except for brief stops at the train station and bus station. The Gallery of Modern Art with its poignant exterior and interior decoration and use of space was one of the most impressive buildings I saw.

Tracy A. Burns is a writer, proofreader and editor in Prague.

Landscape, 1962 by Vladimír Boudník

Apollo and Dionysus, 2013 by Anna Hulačová

The gallery also has an impressive collection of contemporary art.

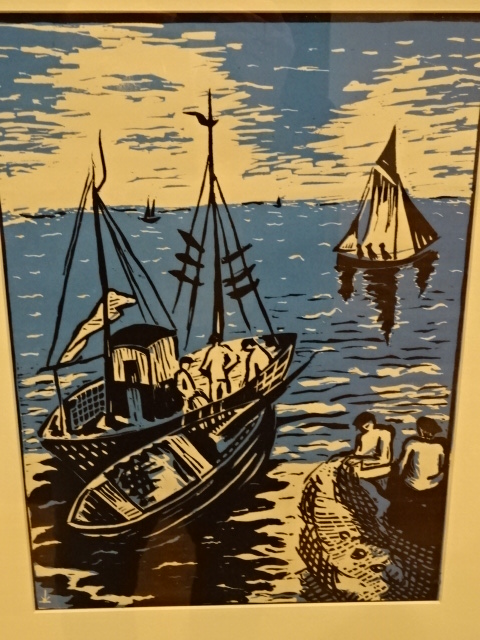

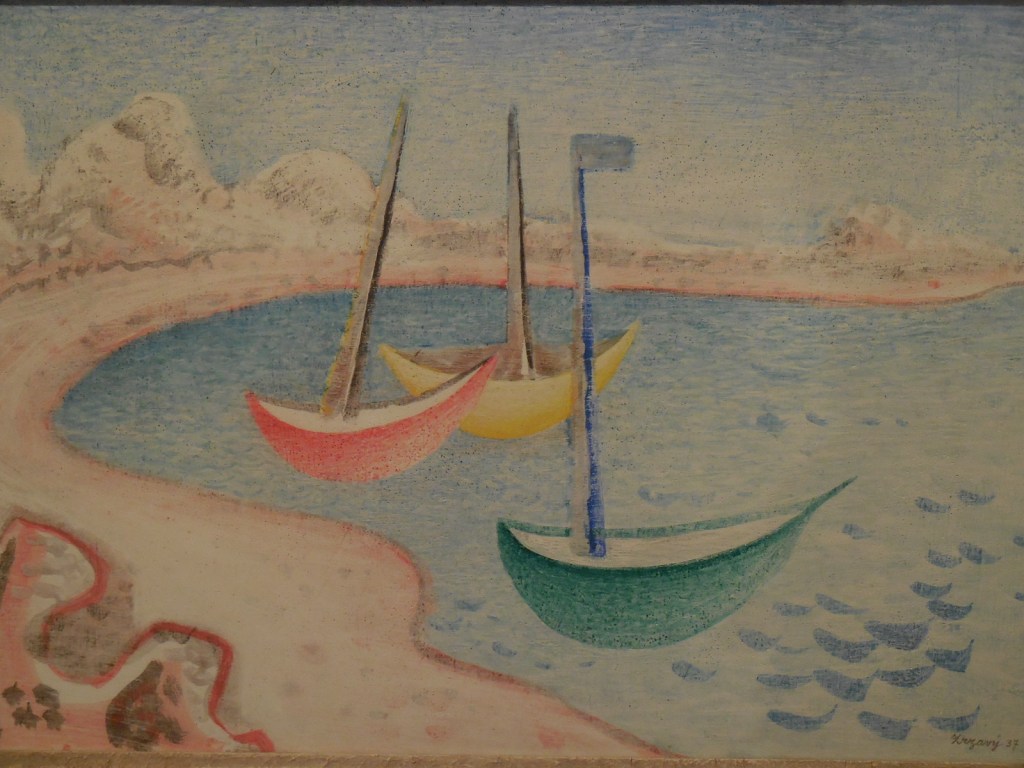

Beach in Crimea (In A Small Bay), 1936 by Věra Jičínská, temporary exhibition

See my post Věra Jičínská Exhibition Diary for more information on this temporary show.