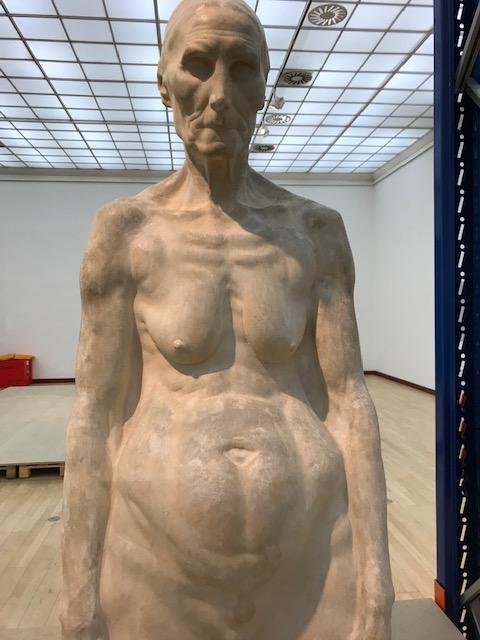

Early in 2023, I went to an exhibition of sculpture by late Croatian sculptor, architect and writer Ivan Meštrović. The art gallery at Prague’s main library hosted the intriguing show. I was familiar with the artist’s name: I had admired his villa, the Ivan Meštrović Gallery, in Split on my last trip to Croatia some years ago. It contained 86 sculptures made with various materials, showing off his dramatic, dynamic and expressive style that was both poetic and poignant. Drawings and reliefs were displayed, too. The bronze statue-dotted garden was delightful. One of my favorite things about traveling was being introduced to the works of various artists. I was enamored with Meštrović’s creations, and his unique, powerful style was forever embedded in my memory.

During Meštrović’s illustrious career that spanned six decades, he had been influenced by a number of styles ranging from Art Nouveau, Symbolism, Impressionism, Art Deco, Neoclassicism and Late Realism. Classicism played a major role in shaping his artistic style, too. Auguste Rodin’s naturalist style, which he had meticulously studied, greatly inspired him. During his extensive travels, Meštrović also saw Michelangelo’s creations, which affected his own work. poignant.

Meštrović’s subjects were diverse as well. He took on religious themes, created portrait busts, made sculptural monuments and delved into studies of figures. A firm believer in promoting Yugoslav national identity, he also presented folk themes and national myths. He fervently advocated for pan-Slavism, and some of his works represented historical events in Slav history.

The sculptor’s career took off when he exhibited his works in Vienna during 1905 as part of the Secession Group. While living in Paris for two years, he received recognition from all over the world and was very prolific. Then he spent four years in Rome, where he was lauded for his design of the Serbian Pavilion at Rome’s1911 International Exhibition. During World War I, he traveled extensively and spoke out against the Habsburg monarchy that controlled his homeland.

He returned to his homeland after the war ended and achieved much success while living in Zagreb. He even created many sculptures for King Alexander I of the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes. He continued to travel, even having an exhibition at the Brooklyn Museum in New York during the 1920s.

During World War II, Meštrović’s life was far from rosy. In 1941, he spent three-and-a-half months in prison. The following year his first wife died, and many of her Jewish relatives perished during the war. Thanks to the Vatican, Meštrović was let out of prison and took off to Venice and then back to Rome. He even met Pope Pius XII.

After World War II, he refused to return to Yugoslavia because the Communists were in control. He wound up in the USA during 1946, when he took a position as a professor at Syracuse University. His works were displayed at the Metropolitan Museum of New York the following year, and he was the first Croatian to do so. He continued to achieve great success and much recognition in the USA and even received the American Academy of Arts and Letters’ Gold Medal in the field of sculpture during1953. American President Dwight D. Eisenhower was so impressed with Meštrović that he gave him US citizenship. Meštrović took a job at the University of Notre Dame in Indiana soon after that. He designed monuments at Notre Dame, and his sculpture is featured in the university’s art museum.

He died in Indiana during 1962 at the age of 79 and was buried in his hometown of Otavice, though the Communists in control of Yugoslavia created many difficulties. His sculptures can be seen all over the world: in Serbia and Romania as well as in the United States, including Louisiana, Indiana, New York and Illinois.

This exhibition focused on Meštrović’s Czechoslovak connection as he had developed an affinity for Czech culture. He befriended the first democratic President of Czechoslovakia, Tomáš Garrigue Masaryk. They both had taken an anti-Habsburg stance during World War I. Also, Meštrović and Masaryk had lived in exile during the first World War. They both admired Slav history. While Meštrović wanted a united Yugoslavia of Croats, Serbs and Slovenes, Masaryk tried to forge a united Czechoslovakia of Czechs and Slovaks. Meštrović sculpted two busts of Masaryk in 1923 as well as busts of his wife Charlotte and his daughter Alice. He created these busts at the Czechoslovak President’s summer residence, Lány Chateau. I recalled spending some sunny afternoons in the park of the chateau in Lány as well as paying my respects at the Masaryk family graves.

Masaryk was by no means the only Czech Meštrović knew. For example, Meštrović was friends with Czech sculptor Bohumil Kafka and even created a portrait bust of Kafka during 1908.

Meštrović’s work was first unveiled in Prague during 1903, when the Habsburgs ruled the Czech lands. His work was included in an exhibition featuring Croatian artists at the Mánes Association in Prague. Mestrovic had another exhibition in Prague during 1933. President Masaryk was so impressed with Meštrović that he presented the Croatian sculptor with the Order of the White Lion award during 1926.

I was enthralled with the Czech connection between Meštrović and artists in Czechoslovakia. Tomáš Garrigue Masaryk was one of my heroes, and I was very interested in life during the First Republic, when Masaryk was president. I felt strong emotions when viewing Meštrović’s powerful works. I also thought back to my introduction to Meštrović’s creations in Split. What a discovery! I was glad to be reacquainted with Meštrović’s sculptures. Seeing his renditions in person was a profound experience.

Tracy A. Burns is a writer, proofreader and editor in Prague.