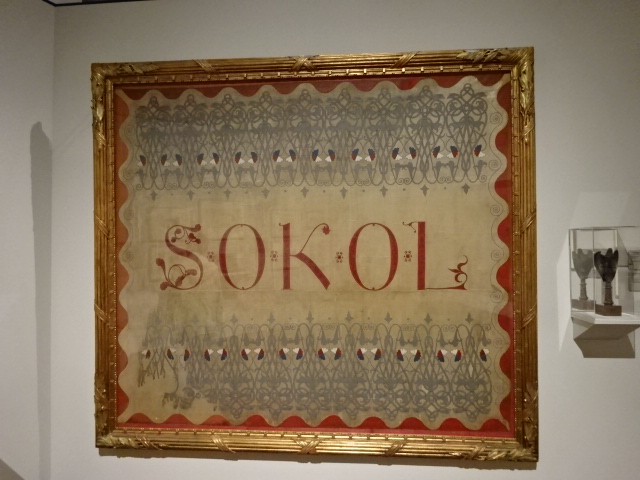

Prague’s Wallenstein Riding Stables hosted a comprehensive exhibition of Josef Mánes’ portraits, genre paintings, landscapes, drawings, prints, designs and illustrations of Slav history from the Czech Romanticism and Realism eras of the 19th century. Some 400 of his creations captured my undivided attention. He also created standards, insignia and uniforms for the Sokol physical education organization, some of which were also on display.

I knew the name well because Josef Mánes had been born into an artistic family: His father, Antonín, created landscapes while his brother and two sisters also became painters. Josef – I will refer to him by his first name so readers do not confuse him with his father or siblings – grew up in the Habsburg Empire when German was the official language of the Czech lands. He spoke only German as a youth. He didn’t learn Czech until he was grown up, even though he was one of the leading figures in the Czech National Revival that promoted the Czech language.

This prominent artist was inspired by his time in Munich, where he spent three years as a young man. For many years he resided in Moravia, including at the Čechy pod Košířem Chateau. In addition to making portraits, landscapes and Second Rococo style genre paintings, Josef developed a strong interest in folk costume, rendering portraits of Czechs in traditional dress. He created many works portraying villagers and everyday life in the Hana region of Moravia.

Inspired by Prague’s Old Town, Josef created portraits of its residents and even painted two genre paintings for Prague brothels. His work also decorated much more elegant structures, such as the Žofín concert hall in the center of Prague, for instance. When I first set foot in Prague, I fell in love with the Old Town. I could sense the history of the nation on its streets and in Josef Mánes’ paintings of that historical quarter.

His portraits are stunning because they are characterized by immense psychological depth and sensitivity. The viewer almost is looking into the sitter’s soul. Each portrait told an individual story of a unique life. Before this exhibition, I had considered him to be first and foremost a portrait painter, but I learned at the Wallenstein Riding Stables that he had been much more versatile in his accomplishments.

I was most enamored by his landscapes because I was fascinated by landscape painting in general, especially by Czech art in this field. I had seen many exciting Czech landscapes in galleries throughout the country as well as in chateaus. Josef’s work utilized subtle colors and masterful brushwork that portrayed both the Czech and Slovak countryside with elements of Romanticism and Realism. He was one of my favorite landscape painters, excelling at employing light and atmosphere in his renderings of the Hana region, the Czech Paradise region, the Krkonoše Mountains and the Šumava Mountains, for instance. I had traveled extensively throughout these parts of the country. Josef’s travels in the Austrian Alps also inspired the creations of some masterful landscapes. While I had never been there in person, I always wound up gawking at the sheer power, beauty and seemingly invincibility of the Austrian Alps. In several other works, he depicted nymphs, using the Šumava Mountains and Moravia’s Čechy pod Košířem as backdrops.

On Astronomical Clock

Astronomical Clock

Perhaps Josef’s greatest achievement was creating 12 medallions for Prague’s Astronomical Clock. I recalled how so many tourists crowded around the clock to watch its hourly show in the late morning and afternoon. I always came to admire the clock in the early morning to avoid the crowds and the possibility of getting pickpocketed. Painted in 1865, the original calendar dial was on display at this exhibition. The allegories of the months of the year dealt with agriculture themes. I often had admired the calendar in the Museum of the City of Prague, where it was usually on display.

Astronomical Clock

I looked closely at the calendar dial, which consisted of circular rings. Standing for the 12 months, figures dressed in folk costume glorified Slav identity. September was represented by the ruins of Troský Castle, which I had seen on my trips numerous times. The Czech village tradition of pig-slaughtering was the focus of December. I remember one irate acquaintance telling me that he did not support the European Union because its regulations did not allow citizens to slaughter their own pigs at home.

Bezděz Castle was in the background of March. I recalled the four-kilometer walk up to the castle ruins that had fascinated me, even though I was not usually so enthusiastic about ruins. A young farmer used a plough in the foreground of the March portrayal. Josef had also painted allegories of zodiac signs. I noticed dolphins and a plump cherub for Pisces. Capricorn was represented by a cherub leading a goat. Romanesque features were evident in Josef’s pictorial work for the dial.

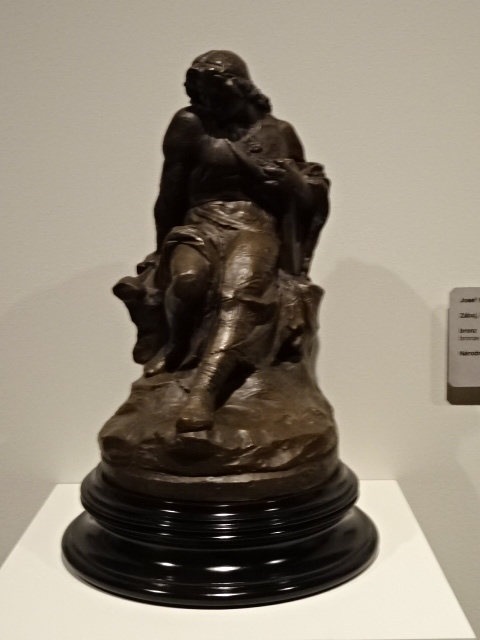

Designed for Sokol physical education organization

Josef’s personal life had not been so rosy, however. After he got a servant pregnant, his parents made him marry her. Josef also was plagued by mental illness from 1866, when he began to lose much weight, to pronounce words badly and behave in a strange manner. It is possible that he suffered from syphilis affecting the brain or tuberculosis. He died in 1871 at the age of 51.

The exhibition also included explanations of how Josef’s work has been perceived throughout the centuries. After his death, he achieved fame because of his work for the Czech National Revival. As the 20th century approached, Josef became known as an artistic pioneer of new trends and advancements in his field. During Communism, though, his works took on an ideological meaning. It was not until after the downfall of Communism that people interested in art could once again express the masterful skill and individuality of his paintings as his works became appreciated in the cultural sphere.

While I had seen many works by Josef throughout the country, I was overwhelmed by viewing so many in one large exhibition hall. I had not truly understood the mastery of Josef’s art and realized that he had been so talented at many genres. For a long time, I had admired the works of his siblings and father, too. Now I knew that Josef was the most skilled in his family. I was fascinated by all aspects of this exhibition.

Tracy A. Burns is a writer, proofreader and editor in Prague.

Josef Mánes