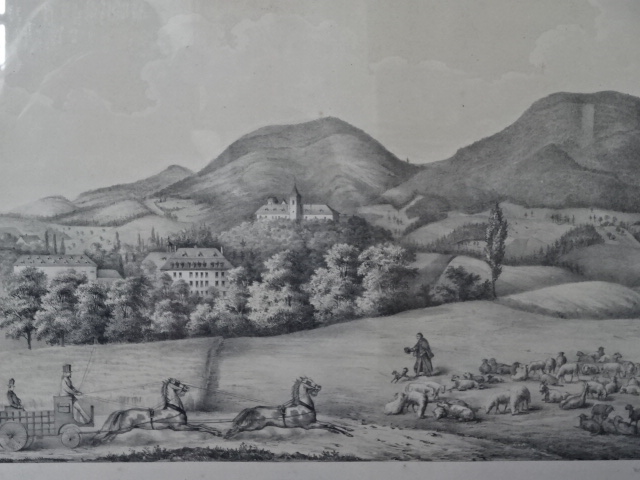

A view of the town

I had visited to the medieval, former mining town of Kutná Hora back in 1992. I recalled exploring the mines, touring the awe-inspiring cathedral and gazing at the Italian Court. I could not forget my visit to the creepy ossuary with shapes made out of human bones. Still, it had been a long time ago. So, in 2012, I decided to return to this special place that for some reason I had not made time for during so many years.

I sharpened my knowledge of the town’s history during the one and a half hour bus ride on that perfect, sunny morning. Kutná Hora gained recognition thanks to its silver mines from the 13th to 15th centuries. At one time, the town’s mine in was the deepest in the world. There was an international demand for its silver, which was exported to one-third of Europe. During Kutná Hora’s golden days of the Middle Ages, the Prague Groschen, a significant currency in Europe, was produced here. Even after the turbulent years during the Hussite Wars in the 15th century and during the Thirty Years’ War of the 17th century, mining in Kutná Hora preserved. The mine was not even shut down from World War II to 1991.

Plague Column in Kutná Hora

I came to the downtown area and soon found myself at the plague column where impressive statues twisted and turned. Then I headed for Saint Barbara’s Cathedral, passing the art museum in the former Jesuit College that hailed from the 18th century. Unfortunately, I did not have time to peruse the art collection during that excursion, but I promised myself to make another trip there in the near future. Too many other sights awaited me on that day. I admired 12 statues of saints, forged from 1650 to 1716, on the way to the impressive cathedral.

A statue on the way to St. Barbara’s Cathedral

I could not help noticing the cathedral’s outer buttresses. The gargoyles and monsters on the neo-Gothic façade were imposing, defending their holy site from evil. (By the way, I love Neo-Gothic!) I had familiarized myself with the history of Saint Barbara’s. Its past had much to do with mining. The cathedral was even named after the miners’ patron saint, Barbara. Although construction started on the cathedral in 1338, it was not completed until 1905. The building was as I had remembered it – absolutely stunning. Once again I marveled at the many Baroque works of art, including three Baroque chapels and a magnificent Baroque organ case.

St. Barbara’s Cathedral

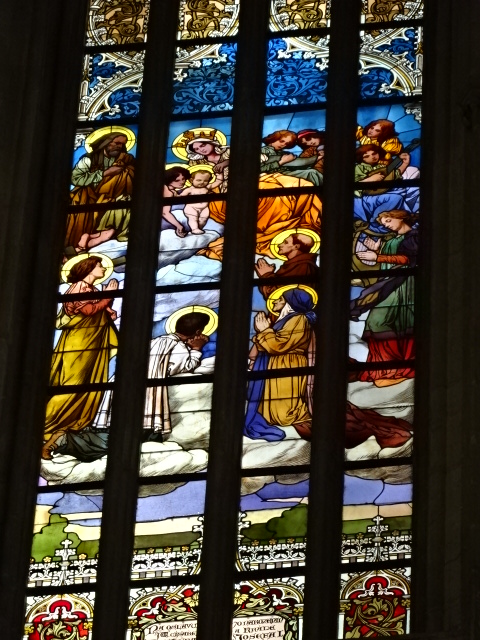

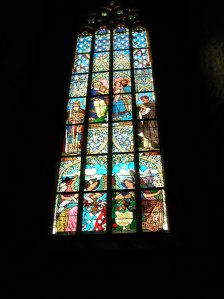

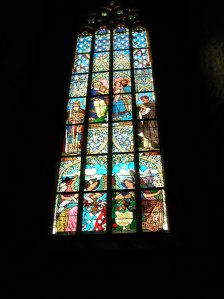

I was particularly drawn to the oldest piece in the cathedral, a statue of Our Lady Enthroned, hailing from 1380. Flanked by two angels in mid-flight, the gold-clad Our Lady gripped a golden orb. The stained glass windows did not disappoint, either. They were exquisite, dating from the end of the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th century. I spotted the cathedral in the background of two of the windows. I also noticed soldiers on horses raising their swords.

Then I came to the unique late Gothic frescoes focusing on the mining profession. I had not seen art with a mining theme anywhere else. In the Mint Chapel frescoes from the 15th century depicted miners making Prague Groschens, striking the coins with mallets. That made me think of how my favorite painter, Pieter Bruegel the Elder, portrayed people at their trades or in scenes from everyday life. A few weeks earlier I had visited the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna, where I had feasted my eyes on 12 canvases by the masterful Bruegel the Elder.

Then I came to the unique late Gothic frescoes focusing on the mining profession. I had not seen art with a mining theme anywhere else. In the Mint Chapel frescoes from the 15th century depicted miners making Prague Groschens, striking the coins with mallets. That made me think of how my favorite painter, Pieter Bruegel the Elder, portrayed people at their trades or in scenes from everyday life. A few weeks earlier I had visited the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna, where I had feasted my eyes on 12 canvases by the masterful Bruegel the Elder.

“The Battle between Carnival and Lent” came to mind. In this depiction celebrating humanity and peasant life, the artist set the scene at a market and church squares. Mass had just ended, and the churchgoers carried their chairs out of the holy building. Crippled people begged for money in front of the church. A corpulent man dressed in pink and yellow stockings was playing a guitar and wearing what looked like a ceramic pot on his head. Bruegel the Elder’s “Seasons of the Year” cycle was another of my favorites. It focused on activities in the countryside. I thought of the depiction of winter, “Hunters in the Snow,” and the hunters in the scene that visually and poetically described man’s relationship to the last season of the year.

The main altar in the cathedral

“Peasant Wedding” also showed the lower class at their trades. A servant was filling mugs with beer, for example. Rich in tradition, it depicted the bride without the groom, seated at the table with her head crowned in a small wreath. A child tried the creamy porridge, licking the bowl. Everyday people were engrossed in what were for them everyday activities, some profession-related, others focusing on leisure. The portrayal of the common man as a miner minting coins was, in my mind, connected to the Flemish and Dutch canvases celebrating everyday life. A statue of a miner appeared in the cathedral as well, which made the relationship with Dutch and Flemish works of art even more apparent.

The exquisite stained glass windows in the cathedral

In another Chapel the Smíšek family huddled around an altar. Saint Christopher carried a child on his shoulders in one large fresco. Then I meandered to the other side of the cathedral, where I saw a mural with a different theme: Created in 1746, “The Vision of Saint Ignatius Wounded in the Battle of Pamplona” showed off angels fluttering through pink clouds. I was also entranced by the stone pulpit, built in 1560. The 17th century ornate wooden pews caught my eye, too.

Hrádek, a museum about the town, mining and silver

After exploring the interior of the cathedral, I was hungry. I stopped for chicken on a skewer at a restaurant with outdoor seating in a courtyard on Ruthardka, a romantic and picturesque street cutting through the center of town. After lunch I stopped by Hrádek or The Small Castle and was eager to see the museum about the town as well as the history of mining and silver in Kutná Hora’s past. The entranceway was full of teenage tourists enthusiastically chatting to each other. I did not want to visit the mines again – I was too claustrophobic – so I asked for the short tour. The man at the box office said he did not think there would be a short tour that day, but maybe he would have one around four p.m., when I had to be back in Prague. I was disappointed as I had read that the former royal residence was decorated with a Renaissance coffered ceiling from 1493 and consisted of halls featuring late Gothic ribbed vaulting. The medieval Saint Václav Chapel boasted wall paintings of Czech saints, I had read. This museum would have to wait until another time.

I carried on to the Stone House, which harkened back to the era before the Hussite period of the 15th century, though it was last reconstructed at the turn of the 20th century. I was fascinated by its richly decorated Gothic façade, even though it dealt with the grim theme of death. I spotted Adam and Eve under a tree in the gable.

The Stone House

First, steep stairs led me down into the lapidary in the basement, which was part of the pre-Hussite structure. The collection boasted stone fragments from medieval times. I was especially enthralled by the pieces of the outer buttresses of the Cathedral of Saint Barbara, especially with the stone set in a fleur-de-lis pattern. I also saw pinnacles, finials and crockets. The angels that had originally decorated the cathedral entranced me, too.

Then one of the guides, a cheerful woman in her forties, gave me a tour of the first and second floors. Part of the first floor was devoted to objects representing the city’s former guilds throughout the centuries. This I what I liked about small museums. They often contained pleasant surprises. I had never seen an exhibition dealing with guilds. One artifact looked like a griffin sticking his tongue out. Two lions and a crown represented another guild. The symbols of the guilds were intriguing.

A closeup of the Gothic facade of The Stone House

In the hallway stood a painted wardrobe and chest with folk themes. I loved folk art, so rich in tradition. Another space featured Baroque and Biedermeier furniture as well as a forte piano from the 19th century. The Baroque desk and wardrobe from the 18th century caught my attention.

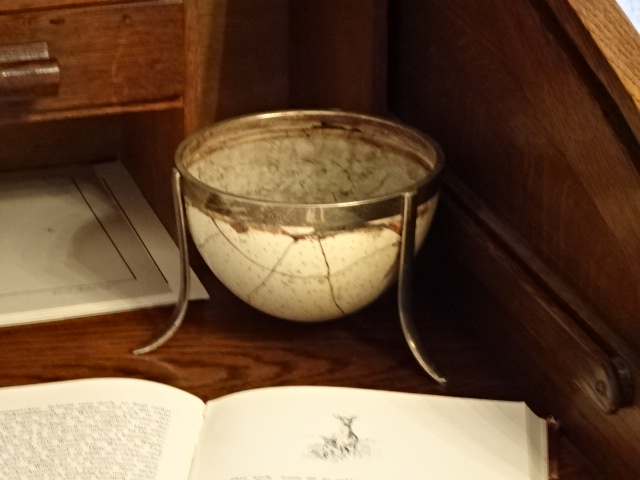

On the second floor relics from religious orders greeted me. A New Testament hailed from 1677. I also saw a silver reliquary and pewter altar vase. Especially intriguing was the small, woodcut relief of Madonna and Child from the 19th century. A Pieta scene from the 18th century captivated me as well. My favorite, though, was a sculpture of Saint Mary surrounded by miners. She wore a star-studded golden halo, her hands clasped in prayer. Bruegel the Elder also dealt with everyday people’s relationship to religion. I thought of the canvas featuring Carnival and Lent again.

The Italian Court

I did not have time to go to the Italian Court that day, but I would come back again soon to visit it. I recalled its royal chapel in Gothic style with Art Nouveau decoration. The Italian Court, hailing from the end of the 13th century, had played a significant role in the town’s history. The Prague Groschen was first minted there. Kings of Bohemia had stayed at the Italian Court, and Vladislav of Jagollen had been voted King of Bohemia there during 1471.

A chandelier made out of human bones

I knew that the 12-sided stone fountain was under reconstruction, so I headed for the suburb of Sedlec , where there was an ossuary and cathedral. A 20-minute walk took me to the ossuary with a cemetery, hailing from the 13th century, the resting place of many plague victims and fallen soldiers from the Hussite wars.

The ossuary in Sedlec

The ossuary in the All Saints’ Chapel went back to the 14th century. I remembered the space being bizarre and morbid yet fascinating at the same time. The Schwarzenberg clan had purchased the ossuary in 1784. They arranged the 40,000 bones and skulls into various shapes. Before that, architect Jan Santini Blažej-Aichel had renovated the space in his unique Baroque Gothic style, which I deeply admired. I gazed at the bones forming a huge chandelier, a Gothic tower and a chalice.

Another decoration in the ossuary

I was enamored with the Schwarzenberg coat-of-arms. Bones depicted a severed Turk’s head and a raven. The chandelier was my favorite, though. I also gazed in wonder at the skulls from soldiers during the Hussite wars of the 1420s in one display case. I could hardly believe that I was looking at skulls that were so many centuries old, skulls that had once been heads of living human beings.

A chalice made out of human bones

Last but not least I visited the oldest cathedral in the country. The Cathedral of the Assumption of the Virgin Mary and Saint John the Baptist has been a UNESCO site since 1995. It was constructed from 1282 to 1320 and got a makeover in Baroque Gothic style by the brilliant Santini Blažej-Aichel.

The cathedral flaunts Baroque artworks

I was astounded by the seven chapels and the renderings of saints. I was very excited to see three paintings by my favorite Czech Baroque painter, Petr Brandl, whose works evoked such strong emotions in me.

An impressive chapel

I admired the Baroque confession booths, hailing from 1730. Saint Vincent’s and Saint Felix’s relics, donated by Pope Benedict XIV in 1742 on the 600th anniversary of the monastery, were also fascinating. The Chapel of the Virgin Mary of Sedlec was impressive with its elaborate Ionic columns and plump putti with angels. The statues originally on the west front of the building intrigued me, too. My favorite was a haloed Saint Benedict gripping an open book. I thought of how literature had opened up new worlds for me, especially the Slovak writings of Václav Pankovčín and his penchant for magic realism.

Once again, Kutná Hora had cast a magical spell on me. I had strolled down medieval streets, toured two cathedrals, visited an ossuary and a museum- all delightful and inspiring experiences. Now it was time to catch the bus back to Prague. One thing was for certain: I would definitely be coming back here. Soon.

Tracy A. Burns is a writer, proofreader and editor in Prague.

A picturesque street in Kutná Hora