I hadn’t visited an aviation museum before fall of 2024 because, quite simply, I had never shown much interest in planes. That all changed when I went to Mladá Boleslav, about 70 kilometers from Prague. The 25 historic planes in this collection – mostly Czechoslovak, German and Soviet – had me hooked.

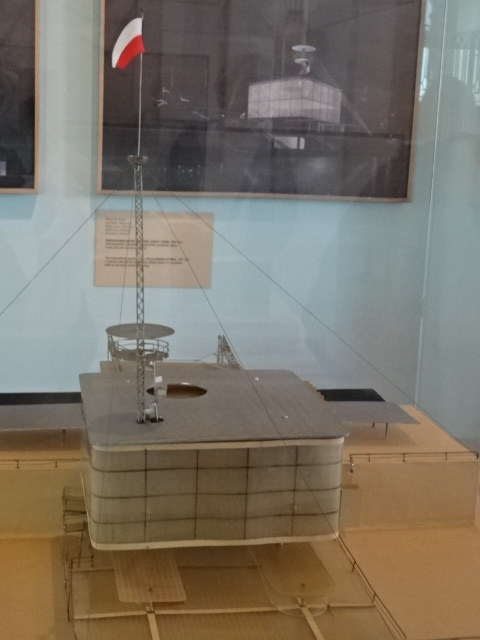

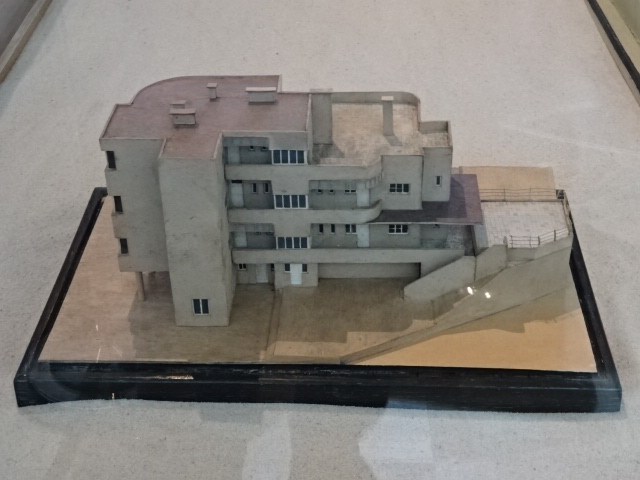

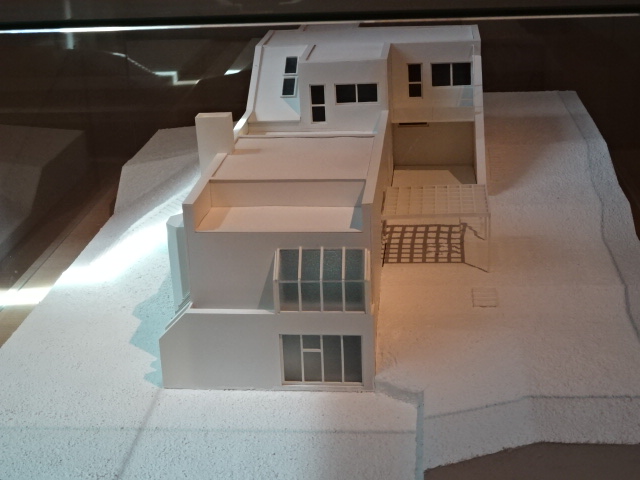

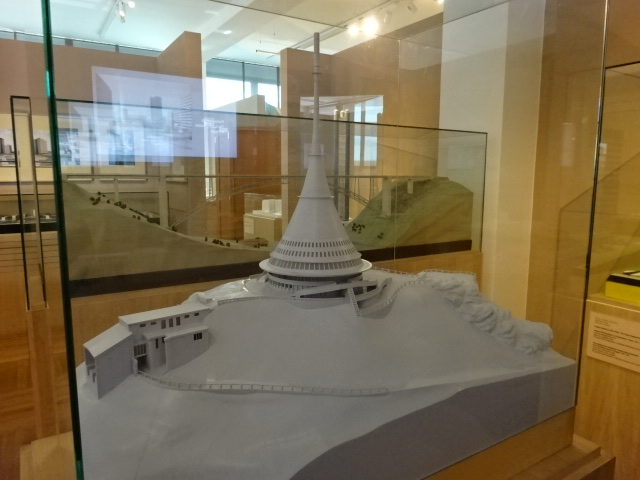

Construction on the museum in a hangar of the Mladá Boleslav airport finished in 2014, and it had been open to the public since 2015. The architecture received much acclaim as it was chosen one of five buildings in the country to be dubbed “Construction of the Year” for 2014. The museum also included two plane simulators and a gyroscope. I perused period uniforms, radio equipment, watches, photography, aviation trophies and posters. From an observation tower there were excellent views of the environs. After walking up steep stairs to the first floor of the museum, I got a good look at the planes hanging from the ceiling.

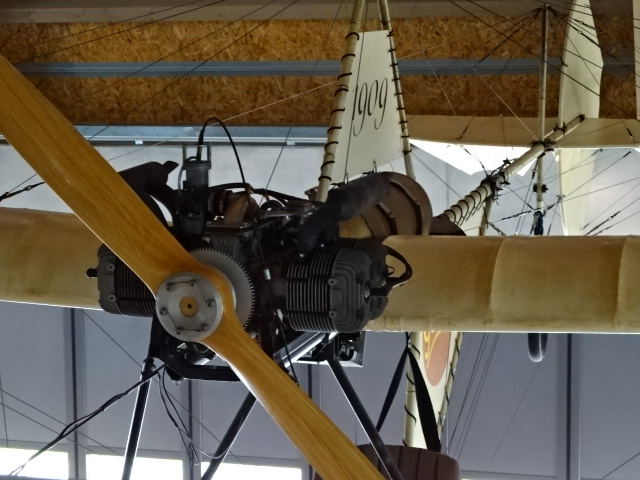

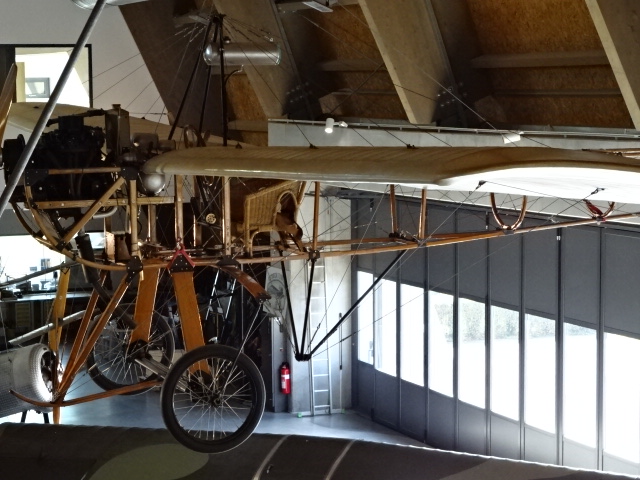

I had not heard of the name Metoděj Vlach before visiting this museum. Vlach had made a name for himself as the first Czech pilot. From 1908 he worked for Mladá Boleslav’s Laurin and Klement business, known for its bicycles and cars, an enterprise that would later become the world famous Škoda automobile manufacturer. He had to use his own money to finance his flying attempts. While his first try was not successful, the second plane he produced in 1909 managed short jumps between 30 and 50 meters. However, the third time was a charm as on November 8, 1912, his aircraft, constructed from 1910 to 1912, made the first flight – reaching 20 meters in the air. It flew a distance of 300 to 500 meters at 100 km/h. The plane weighed 720 kg, and the motor, the kind an automobile used, was 28 kW. The aircraft was successful during five attempts.

One of the aspects about museum-going that I like best is learning about important historical figures and events that I had not known anything about. Learning about Vlach was one of those lessons that certainly enriched my experience at the museum. I spent a lot of time peering at the various specimens, dating from World War I to the later years of the 20th century.

The Little Beetle

A plane called the Little Beetle captured my attention. The first modern Czechoslovak amateur aircraft, the W-01 Little Beatle was built at the owner’s home in Brandýs nad Labem during the 1960s. The public set eyes on the plane for the first time in 1970. With a wingspan of 6.08 meters and an empty weight of 280 kilograms, the Little Beetle was a frequent participant in Czechoslovak air shows. It was five meters long and could fly up to 180 kilometers per hour. During the mid-1970s, international audiences took notice of the Little Beetle as it was shown off in airshows that took place in the German Federal Republic, Holland and England. Sadly, an accident in 2003 ended the Little Beetle’s career. During 2015 the specimen was brought to this aviation museum.

German Bucker Bu 130 Jungmann

I also took notice of the German Bucker Bu 130 Jungmann, a two-seater designed for training and aerobatics. It took off for the first time in May of 1934 and became a popular training aircraft for the Luftwaffe. The Germans were not the only ones to use this model aircraft, though. It received worldwide acclaim in Czechoslovakia, Spain, Japan, Hungary, Switzerland and other countries.

PO-2, The Sewing Machine or The Maize Cutter

Another plane with an interesting history was the PO-2, a prototype of a U-2 biplane that was adopted by the Soviet Air Force. It was also used for civilian aviation. More than 40,000 PO-2 planes were produced. This popular two-seater came into existence during 1927, and production started the following year. During World War II the Germans called the plane “The Sewing Machine,” describing the distinctive sound of the engine. Soviets had a different nickname for the aircraft with an engine of 100 to 115 horsepower. They dubbed it the “Maize Cutter.” It was also historically significant because a regiment of female Soviet pilots conducted nighttime air raids on Germany using this aircraft. The Germans dubbed these female military personnel “Night Witches.” Production did not stop when the war came to a close. The PO-2 was manufactured in Poland post-wartime.

Klemm L 25

I took note of another German plane. The Klemm L 25 aircraft was designed by Dr. Ing. Hanns Klemm, created in 1926. It was possible to use various kinds of engines with these training, sports and aerobatic planes. About 600 planes were manufactured from 1928 to 1939. During the 1930s the Klemm L 25 participated in competitions in Germany.

Zlín Z-50L

I also saw the Zlín Z-50L aerobatic plane made in Moravia. In the 1970s and 1980s its pilots clinched first place in international competitions, both European and world championships, while flying this plane. The last world championship won by this aircraft was as recent as 1989.

Be-60 Bestiola

The two-seater, wooden aircraft called the Be-60 Bestiola was designed in 1935 as a Czechoslovak aircraft to be used for training and tourism purposes. Its life span was relatively short, though, as production was halted not long after the 1939 Nazi Occupation. Some of these planes were flown by the fascist-oriented Slovak State during World War II. Unfortunately, there are no longer any original planes of this type in existence. The replica in the museum is quite impressive, though.

Zlín Tréner

Used for training and aerobatics, the Zlín Tréner captured my attention. It was a two-seater monoplane with low wings and first took off in 1947. Later, it was powered by a four-cylinder engine and was composed of wings and tails made of metal. The career of that prototype began in 1953. The wingspan measured 10.26 meters while the take-off weight was 750 kilograms. The engine was 105 hp, and the maximum speed it could reach was 203 km/h. The aircraft has had a stellar career and is still used for training.

G – III plane

Brothers Gaston and Réné Caudron had been plane designers since 1909. Their G-III did a loop for the first time in December of 1913. In May of 1917 ,it hit another milestone by setting a new record: It flew non-stop for 16 hours and 28 minutes. About 150 planes of this type were produced. The aircraft had a wingspan of 13.4 meters with a take-off weight of 735 kg.

Fokker E.V.

I also saw the Fokker E.V. German fighter plane from World War I. Some 289 aircraft of this model were manufactured. The planes were 5.85 meter long and utilized a 110 hp or 160 hp engine. The wingspan was 8.35 meters while the take-off weight was 605 kg. It could go as fast as 200 km/h.

ŠK – I Trempík

The two-seater ŠK – I Trempík was known for its stability. It was not difficult to take care of, either. Its wingspan measured 9.3 meters, and it was powered by an engine of 75 hp. The maximum take off weight was 578 kg, and it could fly 185 km/h.

1926 silent film with Alexander Hess as the pilot

General Hess after returning from his service in the RAF when he shot down two German planes; British royal George VI awarding Hess a medal; War plane Hawker Hurricane used by the general

On the first floor there were panels about General Alexander Hess, a pilot I had not heard of before. He also had starred in a 1926 silent Czechoslovak film as well as working as a pilot. Hess was the organizer of the Czechoslovak aircraft for the 1936 Olympics. After the Nazi Occupation in 1939, he helped pilots escape, equipping them with false passports, and General Hess wound up fleeing from the Nazi Protectorate to France and then to the USA in January of 1940. After World War II, he returned to Czechoslovakia but fled again, this time from the Communist regime. General Hess settled in New York City, where he worked as a technical assistant with PAN AM.

So I became acquainted with the career of not only Metoděj Vlach but also that of Alexander Hessman. I found the exhibit most intriguing. In fact, the entire museum was engrossing with so many planes from various countries and eras, each unique with compelling attributes. While I still despised the eight-hour flights from Europe to the USA, I comprehended the historical importance of these aircraft. In Mladá Boleslav for the first time, the city made a good impression on me. After visiting this museum, I would take a look at the Škoda Museum of bicycles and automobiles, another delight.

Tracy A. Burns is a writer, proofreader and editor in Prague.