Caricature of Laocoon, Niccolo Boldrini, 1540-45, woodcut.

In the exhibition “From Michelangelo to Callot: The Art of Mannerist Printmaking,” held at Prague’s Wallenstein Riding Stables, I studied more than 200 works of 16th and 17th century graphic art, drawings, paintings, jewelry, etchings, lithographs, ceramics and other artistic crafts that hailed from the Netherlands, Germany, France and the Czech lands. The Louvre lent Prague’s National Gallery many works. Some pieces in the collections were being displayed to the public for the first time. A superb small drawing by Michelangelo drew crowds, and art by Hendrick Goltzius, Paul Bril, Aegidius Sadeler and Niccolo Boldrini stood out to me.

The Great Hercules, Hendrick Goltzius, 1589, engraving.

While Mannerism became a major trend during the 16th century in Italy, Northern Mannerism lasted into the 17th century. Because European artists north of the Alps did not have as many opportunities to travel to Italy in order to familiarize themselves with Mannerism, they often studied the style through prints and books. The decoration at the Chateau of Fontainebleau impressed many artists utilizing this style, and France was the center of the Mannerist movement. The Northern Mannerists also looked to da Vinci, Raphael, Vasari and Michelangelo for inspiration.

The Martyrdom of Saint Lawrence, Cornells Cort, 1571.

The Northern Mannerist style was very visible in Holy Roman Emperor Rudolf II’s collection in Prague, then the capital city. Influenced by prints, Mannerism appeared in Prague during 1576. An avid art collector, Emperor Rudolf II had hired the Flemish painter Bartholomeus Spranger and German artist Hans von Aachen to work for him, and they produced some works in Northern Mannerist style. Both Spranger and von Aachen were known for their Mannerist mythological scenes while von Aachen also concentrated on portraits of the emperor. Rudolf II’s father, Emperor Maximillian II, had chosen Giuseppe Arcimboldo as one of his painters, and Arcimboldo’s fantasy-filled still lifes and portraits feature Mannerist traits. This style also suited Rudolf II when he took over for his father.

The Combat of the Monkey and the Rat, Christoph Jamnitzer.

Mannerist art often included mythological scenes, the grotesque and fantasy. Harmony, symmetry and rationality were notably absent. While Mannerists showed a great interest in anatomy, the figures were often elongated, and many forms had a sculptural quality. Clothing was elaborate. Attention to detail prevailed. Complex and unstable poses as well as dramatic lighting also characterized the Mannerist style. Artists of this era liked to employ symbols and utilize hidden meanings in their works. Black backgrounds were common. A distorted perspective was employed. Mannerism did not often feature religious themes. After Mannerism came the Baroque style, which focused heavily on religious art.

The Last Judgment, Michelangelo, 1536-1541.

The Last Judgment, Michelangelo.

The Last Judgment, Michelangelo.

The Last Judgment, Michelangelo.

A copy of a section of “The Last Judgment” as seen in the Sistine Chapel was on display at this exhibition, as this masterpiece greatly influenced Mannerist art. This fresco at The Vatican portrayed more than 300 figures as the dead made their way to idyllic Heaven or horrific Hell. Mythological figures and devils appeared along with a beardless Jesus Christ, the Virgin Mary and saints. I noticed the looks of horror on descending figures. Details in superb portrayals of human anatomy greatly impressed me.

Head of a 12-Year Old Christ, Albrecht Durer, 16th century.

For me, German Albrecht Durer’s 16th century “Head of the 12-year old Christ” was one of the highlights in the exhibition. Durer was a master of High Renaissance printmaking, especially of woodcuts and engravings. He inspired Raphael and Titian. I realized how Durer’s portrayal of human anatomy had impressed Mannerists. While most works displayed did not focus on religion, the Mannerist engraving “The Martyrdom of Saint Lawrence” from 1571 also caught my attention. Cornells Cort created it in the style of Titian.

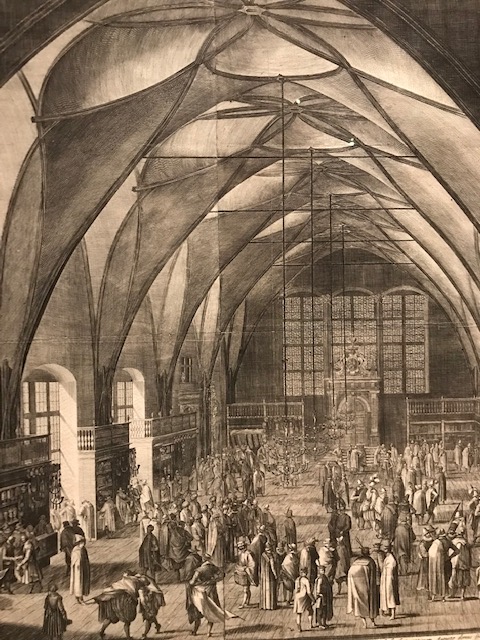

Vladislav Hall, Aegidius Sadeler, 1607.

Some prints showed off specific architectural structures, such as Aegidius Sadeler’s Vladislav Hall from 1607. A fan of Czech architectural history, I was especially engrossed in this rendition of the late 15th century and early 16th century section of Prague Castle built by Benedikt Reid. I loved its complex vaulting system. I noticed Late Gothic and Renaissance elements of the building. This was one of my favorite buildings in Prague due to its exquisite vaulting and its past use for historical events, such as coronations and knights’ tournaments.

Wooden Bridge from Series Eight Bohemian Landscapes, Aegidius Sadeler, 1605, engraving.

Mountain Landscape, Paul Bril.

Another work by Sadeler, created in the style of Pieter Stevens, was the landscape “Wooden Bridge from Series Eight Bohemian Landscapes.” The 1605 engraving of the idyllic, romantic bridge reminded me of picturesque Vermont, where I had lived for a while. I was also enamored with “Mountain Landscape” by Flemish painter and printmaker Paul Bril. Inspired by my favorite artist Pieter Bruegel the Elder, Bril authored works in the Vatican and Italy. I appreciated the power and beauty of nature as I peered at these two tranquil landscapes.

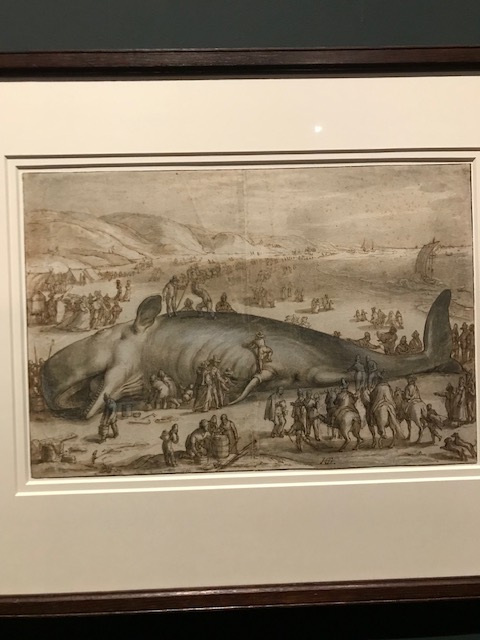

Beached Sperm Whale near Berkhey, Hendrick Goltzius, 1598.

A prominent name in the exhibition, Henrick Goltzius was a stellar printmaker whose works were influenced by drawings he acquired from Prague. My favorite of his contributions was “Beached Sperm Whale near Berkhey” from 1598. People gathered around the gigantic, deceased animal. This artwork was inspired by a real event as a 58-foot long whale had washed up on that shore.

The Four Disgracers, Hendrick Goltzius, 1588, engraving.

The Four Disgracers, Henrick Goltzius, 1588, engraving.

Goltzius also took on mythological themes, such as his rendition of “The Four Disgracers (Tantalus, Icarus, Phaethon and Ixion).” This engraving appeared to have a three-dimensional quality. The illusion of three-dimensional features, mastered by engravers in the Netherlands during the late 16th century, was often featured in Northern Mannerist art. Goltzius was the author of “The Great Hercules,” an engraving from 1589. The detailed anatomy, though not correct, interested me. Other works with mythological themes that caught my attention were “Diana and Actaeon” by Joseph Heintz the Elder from 1597 to 1598 and Niccolo Boldrini’s “Caricature of Laocoon,” a woodcut from 1540 to 1545.

The Pairs of Grotesque Heads, Philippe Soye, 1550-65.

The grotesque played a significant role in Northern Mannerist creations. Philippe Soye rendered “The Pairs of Grotesque Heads” after a masterpiece by da Vinci. Soye’s portrayal hailed from 1550 to 1565. Christoph Jamnitzer also stressed grotesque features in his “The Combat of the Monkey and the Rat.” I was also impressed with the masked figures in “Venetian Carnival,” a 1595 engraving by Pieter de Jode the Elder. Seeing the grotesque made me think of gargoyles on cathedrals, such as Milan’s Duomo or Saint Vitus’ Cathedral in Prague.

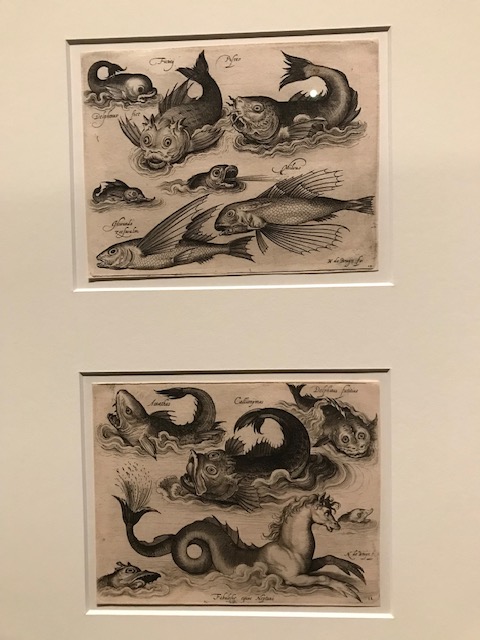

Fantastic Sea Creatures, Nicolaes de Bruyn, 1594, engraving.

Prints with scenes immersed in the fantasy world made numerous appearances. At the end of the 16th century, Nicolaes de Bruyn became known for his portrayal of animals and fictional sea creatures. His “Fantastic Sea Creatures,” depicted here from a series, was an engraving that made up part of a book about fish. Engravers often worked with fantasy themes in this style.

Diana and Actaeon, Joseph Heintz the Elder, 1597-98.

A section of the exhibition was devoted to Northern Mannerist decoration of objects such as vases, plates, mirrors and jewelry. Adornment was often floral or geometric, and I noted similarities to illuminated manuscripts. Artists of this sort of ornamentation were inspired by the grotesque, mythological figures and Roman wall paintings, for instance. I saw examples of mythological themes and the grotesque in the decoration of a majolica plate from the second half of the 16th century. A 16th century black enamel mirror exuded elegance with Mannerist designs.

Venetian Carnival, Pieter de Jode the Elder, 1596, engraving.

The exhibition was comprehensive, divided into clear sections. I was drawn most to the landscapes as I was reminded of the work of Pieter Bruegel the Elder. I also thought of Paul Bril’s creations in Milan’s Ambrosiana Picture Gallery. It was intriguing that the scenes on many prints showed the main figures in the background and the lesser important ones in the foreground. I liked the decorative patterns that were influenced by illuminated manuscripts. I spent my fortieth birthday gazing at the Sistine Chapel and mulled over the experience of seeing those writhing, terrified souls guided by devils and the blessed blissfully ascending into Paradise. I also thought of the awe-inspiring experience of walking into Vladislav Hall because I loved Late Gothic vaulting. That print captured the daunting atmosphere perfectly. Seeing a masterpiece by Durer brought me back to an exhibition of his works at the Albertina in Vienna some years ago. I could hardly catch my breath because I had been so impressed. I had learned a lot about Mannerism from this exhibition and had discovered works that I would never forget.

Tracy A. Burns is a writer, proofreader and editor in Prague.