Peering at the paintings in the third floor art gallery and the furnishings on the first floor representative rooms, I came quickly to the conclusion that Radim Chateau was a hidden gem among sights near Prague. While there were not numerous spaces to visit, the ones viewed on tours of the representative rooms were outstanding in their content and beauty. Everywhere I looked in the gallery and on the representative floor, I saw magnificent artwork. Even the 19th century tapestries and Romantized furnishings in the hallways told intriguing stories of centuries gone by.

I was stunned by the masterful artistry of Radim Chateau during my first visit in 2025. This Renaissance chateau in central Bohemia was built next to a fortress that was first mentioned in writing during the early 14th century. The fortress had various owners. Then Karel Záruba from Hustířan had the chateau constructed in the early 17th century. The two-floor structure was ready for use by nobles in 1610. However, Karel passed two years later, and the property became the possession of his son Jan, who took the side of the defeated Protestants during the Thirty Years’ War. Because the Catholics triumphed, the chateau was confiscated, and Jan had to flee the country. However, when Adam the Younger of Wallenstein took over the chateau and property, he returned it to Jan Záruba. Soon it was purchased by the legendary Šternberk clan. At that time, Radim became an administrative seat where clerks rather than nobles occupied the chateau.

Several owners came and went after 1634. Then, in 1685, the well-known Gallas family took over Radim and held onto it until the 18th century. I thought back to the Clam-Gallas Palace in Prague, where the ceiling frescoes and ballroom with crystal chandeliers are superb. Getting back to Radim history: The next owner was a notable pioneer in the Czech publishing industry, the knighted František Jan Brahier. He printed breaking news in German. When Brahier died in 1721, he did not leave any heirs.

That is when the Kinský family came into the picture. A family that had had so much influence on horse breeding and horseracing, the Kinskýs sold the chateau to Prince Alois Josef Lichtenstein in 1783. This was an important purchase because the chateau stayed in this family for 143 years. During the Lichtenstein reign, the chateau once again served administrative purposes for a significant period of time.

A momentous occasion could have taken place in 1791, if fate had not gotten in the way. The Czech king Leopold II was returning to Vienna from his coronation in Prague and wanted to see Radim Chateau and take in some hunting there. However, plans had to be changed as Leopold II had to hurry back to Vienna without a hunting break. In the early 19th century, there was much reconstruction.

The Lichtenstein’s parted ways with Radim in 1927, when Dr. Jaroslav Bukovský took charge. Many changes took place as he used the chateau for representative purposes. Electricity was added to the chateau, and what was once a French park came to flourish in English style.

During the Nazi Occupation, the German army used the premises, although the owner’s wife, Mrs. Bukovská, was still allowed to have a small apartment there. After May of 1945, the Russian military took control of the chateau. The Communists held it from 1950, when Mrs. Bukovská was still permitted to reside on the premises in a tiny abode. Most of the chateau was changed into offices, and a few apartments were installed. District offices remained in the chateau until the 1990s. Then in restitution the Bukovský family got the chateau back. After selling the chateau in 2005 to Antonín Dotlačil, much reconstruction took place.

The chateau was sold again, this time to the present owner, Bohuslav Opatrý, who is a music and art lover, having restored many of the paintings in his third floor collection. The park and garden underwent reconstruction as did part of the chateau. It was not until this century that Radim Chateau was open to the public.

While most of the furnishings are not original due to the Nazi occupation of the chateau and the dereliction that occurred during socialist times, it does boast original 19th century flooring in the main hall. To be sure, the Communists destroyed most of the chateau interior. Yet, decades later, Radim would be resurrected by painstaking efforts that made it into the gem it is today. The painted ceilings in the bedroom, main hall and gallery have been preserved to a great extent. The painted decoration on several ceilings, such as a lobster and a horse, hails from 1607 to 1610.

In the bedroom that we entered first, I was intriguing by the Baroque bed with exquisite carving. In the dining room, I was speechless at the sight of low Renaissance chairs around a Renaissance table. In other rooms, I saw many Gothic chairs, often Romanticized into 19th century style. A Mannerist cabinet with exquisite woodwork of figures and columns was a delight in one space. I spotted a portrait of Rudolf II among the pictures of rulers that decorated a high wall in the bedroom. I also saw in one space a 18th century globe decorated with allegorical figures of zodiac signs instead of continents. The ceiling decoration of a green-and-white pattern in the bedroom also awed me. So delicate and so much attention to detail.

In the administrative office of the Lichtensteins, I saw pictures of Austro-Hungarian generals. In the study, portraits of past owners as well as the current owner hung on the walls. I recognized Adam the Younger Wallenstein as well as Adam Kinský. There was even a portrait of Octavian Kinský, who was never the owner of this chateau but had made a name for himself with that clan, specifically in horse breeding and horseracing. Work related to his successes could be seen in Karlova Koruna Chateau, which I had visited several times. A more modern likeness of the current owner also decorated one wall. In an isolated space, I peered at a Neo-Gothic altar with medieval elements. Tapestries from the 19th century were present throughout the chateau’s first floor and hallways.

The main hall, often used for weddings, was one highlight of the tour. The painted ceiling featured various objects and animals in bright colors. A 19th century Petrov Grand piano also adorned the space. Paintings from various periods added to the décor.

Close-ups of the Mannerist cabinet

On a tour of the cellar places it was possible to see a Black Kitchen that was still functional as well as an armory and some bedrooms once used by princesses. This was another intriguing tour.

Portrait of Austrian general

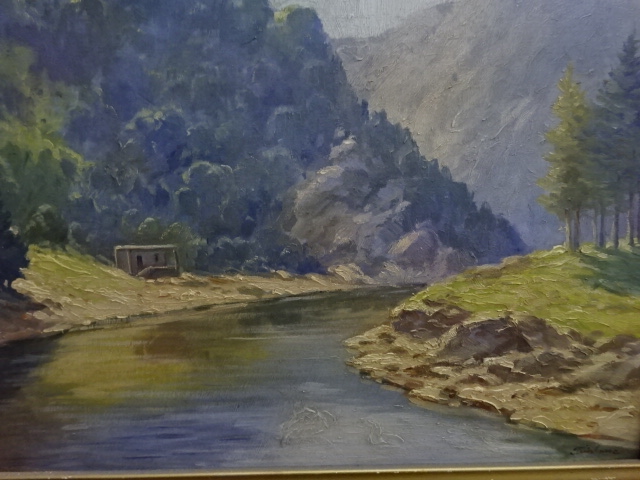

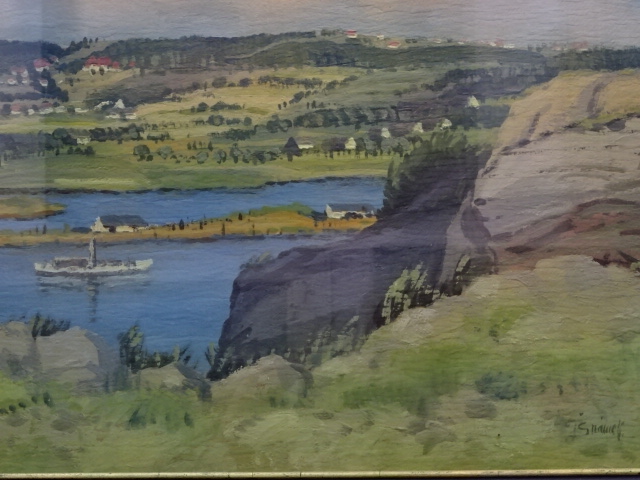

However, the biggest highlight for this art lover was the gallery on the third floor. Nineteenth and early 20th century landscapes dotted the hallway. I saw images of the slowly flowing Berounka River, the snow-covered Alps, charming cottages tucked into woodlands, the tranquil landscape in the Pilsen region, sights of Prague, portrayals of sheep, folk dancing figures and haymakers doing laborious work in the fields, mystical forests and other scenes. I was enamored by each painting as landscapes from this time period were my favorite. While most of the paintings were authored by lesser known artists who deserved much praise, one work was painted by the well-known Otakar Nejedlý.

Landscape with Berounka River, not by Nejedlý

This renowned Czech painter lived from 1883 to 1957. He was a pupil of the master landscape artist Antonín Slavíček. His travels to India greatly influenced his works. During World War I, he was mobilized to France where he painted places the Czech legionnaires had fought. After the war, he became an esteemed professor in Prague. He adored the south Bohemian countryside and was inspired by Romanticism, Impressionism and Expressionism.

Painting of sheep by Popelka

Vojtěch Hyněk Popelka created the renditions of moving sheep, and it was no surprise that he specialized in painting animals. He brought to life landscapes and animals in his works during the early 20th century.

Painter Otto Stein, who also was an accomplished graphic artist, lived from 1877 to 1958. Several of his works were displayed in this gallery. After studying in Prague and settling in Munich, he took part in Munich New Secession exhibitions in the early 20th century. During the war, he painted material used to promote the Austro-Hungarian Army. After the war, he became part of the Berlin Secession, having to move to that city. In 1922 his renditions were on display in Prague’s Rudolfinum. He gained acclaim in Germany and the USA.

In 1942 tragedy struck, and he and his family were deported to the Terezín concentration camp. He toiled in the technical department there and bided his free time with drawing. Miraculously, he and his entire family were spared, and, after the war, he moved to Prague. Then he went to live in the north Bohemian countryside, where he did a great deal of painting. He died there in 1958.

The German painter Adrian Ludwig Richter also had works on display in this gallery. He lived from 1803 to 1884 and also succeeded as a illustrator. His paintings featured the Romanticist style, inspired by Caspar David Friedrich. He was especially enamored with the countryside of north Bohemia and the ruins of Střekov Castle in that region. Richter also made 3,000 creations out of wood.

Vlastimil Toman (1930 – 2015) was a painter, graphic artist, illustrator, poet and photographer as well as professor. Several of his landscapes were represented in the gallery. He worked mainly in Třebíč, painting the Vyšocany and Moravian countryside. In the 1960s, he explored the styles of cubism, fauvism, expressionism and lyrical realism. In total, he had 24 solo exhibitions in Třebíč plus 50 collective exhibitions around the country.

Prague Castle in the distance

Čertovka on Kampa Island, Prague

My favorites were the renditions of Prague. One painting featured Prague Castle in the horizon, another showed the Charles Bridge. Yet another displayed the Judith Bridge, which preceded the Charles Bridge. One portrayed Čertovka on Kampa Island.

But there was more. A rather large space featured religious art. I saw numerous madonnas, scenes from the Bible and pictures of saints here as well as Gothic furniture. There was a range of styles, and works hailed from various eras, though none were modern. My head was swimming with this immersion into religious art.

From the third floor, it was easy to read the motto of Saint Benedict on the balustrade. “Tempora matuntur et nos matumar cum illus,” it read. It meant that times change, and we change with them. Other black-painted letters read “Ora et labora,” which translates from the Latin into “Pray and work.” The ceiling on the third floor was richly decorated with depictions of objects and animals.

Not only had I peered at masterfully carved furnishings and other notable objects in the representative rooms but I had also viewed numerous paintings in my preferred landscape genre. The religious art was very impressive, too. While the chateau’s representative spaces are not large, it is worth seeing for those interested in Czech history and sights with artifacts from various eras. Art enthusiasts are sure to love the third floor displays.

On that day there was a wedding, and the café offered various cakes and pastries outside as well as sausages that were cooked over a fire. Delicious bread was available, too.

I went to lunch at U Marka restaurant in Pecky, a small town nearby. The rustic interior was suitable for the delicious Czech food, which cost so much less than that in Prague. I had had a great day.

Tracy A. Burns is a writer, proofreader and editor in Prague.