Painting of Jezeří by Carl Robert Croll

From the chateau interior

The first time I visited Jezeří Chateau was around the year 2000, about four years after it had opened to the public. While the chateau dominating the mountainous landscape appeared impressive from afar, up close it had looked derelict, as if it was about to collapse. The tour had covered only several rooms because much of the structure was under reconstruction. I left Jezeří feeling sad that a chateau with such promise had been derelict for so long. I wondered if the state would ever be able to make the chateau presentable again as so much rebuilding was necessary.

Now, 24 years later, I went back to the chateau situated in the Ore Mountains near the German border. About 10 rooms were open to the public, and they were impressive. I especially loved the paintings of Carl Robert Croll and the room where former Minister of Foreign Affairs and son of the first Czechoslovak President, Jan Masaryk, had stayed overnight. Spaces that had once succumbed to a sad plight now impressed, many harkening back to the golden days of the chateau.

The main facade of the chateau

But it is necessary to start at the beginning and get to know Jezeří’s history and suffering throughout years of dilapidation before touching upon the current appearance. To appreciate Jezeří fully, one has to be aware of the chateau’s journey, a long and winding one that overcame many obstacles.

Atlantis statue on main portal of the chateau

Jezeří Chateau dominates the landscape as a Baroque structure in the Ore (Krušné) Mountains of north Bohemia. It had been transformed from a Gothic castle called De Lacu (from the lake) to a Renaissance chateau by the Hochhauser family and finally to its Baroque appearance today. It was first mentioned in writing as a Gothic castle in the 1360s. The Thirty Years’ War brought much damage and destruction.

Statue of a dog above the main courtyard of the chateau

Then, in 1623, Vilém the Younger Popel Lobkowicz bought it, and the Lobkowicz name would punctuate the chateau’s history for centuries. Under Ferdinand Vilém Lobkowicz, from 1647 to 1708, extensive reconstruction took place. The property included 500 hectares. A hall replete with grandeur showed off oval vaulting, stucco decoration and large columns while a new richly decorated dining room sported a beautiful ceiling. Rooms were adorned with frescoes. The garden showed off fountains and cascades. A zoo was on the premises. However, all good things came to an end when a fire that could not be extinguished ravaged the building during 1713.

During 1722 the chateau passed into the hands of the Roudnice branch of the family. Jezeří would come to life again when reconstruction occurred during the 18th and 19th centuries. Jezeří flourished, filled with frescoes and paintings by masterful artists. The English style garden included an artificial grotto and lavish statues. The H-shaped chateau became a center for musical and theatrical events during the Baroque and Classicist eras as famous guests visited its renowned theatre.

View of oratory of chateau chapel

Owner Maxmilián had opera singers visit from ensembles in Vienna and Dresden. Beethoven was friends with Prince František Maxmilián. The first private performance of Beethoven’s third “Eroica” Symphony, which the composer had dedicated to František Maxmilián, took place here. It also was the site of the first private performance (1797) of Haydn’s Creation. My favorite symphony by Beethoven, his sixth (the Pastoral), was also dedicated to Prince Lobkowicz.

Sculpted heads with facial expressions adorn the Theatre Hall.

Another sculptural decoration in the Theatre Hall

At the time, vast Jezeří was buzzing with excitement in its 114 rooms and numerous smaller spaces. The English gardens and park were Baroque in style and showed off statues of mythological figures, greenhouses, pavilions, an artificial waterfall, terraces with magnificent views and an arboretum.

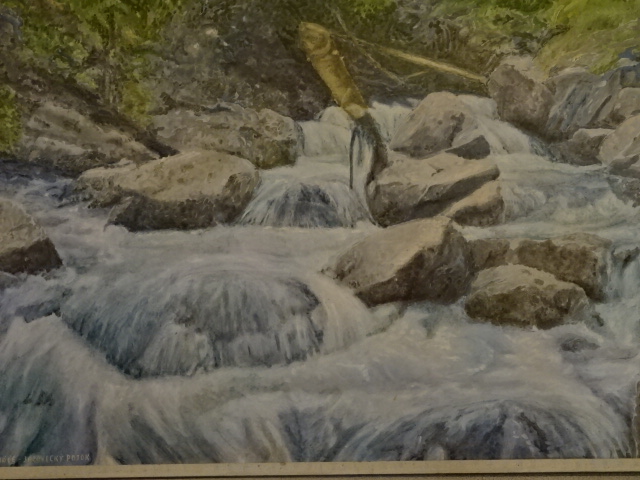

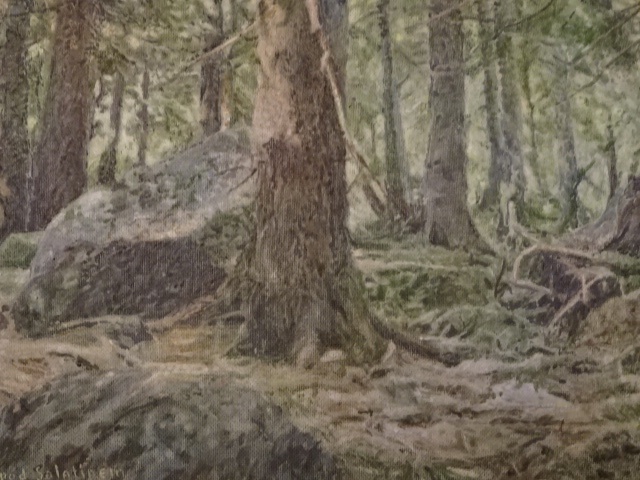

Painting of chateau interior by Carl Robert Croll

In the early 19th century, the prominent painter Carl Robert Croll created canvases for the Lobkowiczes, and his renditions of the chateau’s exterior and interior are magnificent. His “Winter Garden” from 1841 portrayed a light and airy room with many plants and windows, white walls and blue-upholstered furniture. The painting “The Big Salon,” created that same year, showed children dancing and men immersed in a game of billiards. Croll’s work “Smaller Salon at Jezeří” focuses on women and girls chatting and ordering tea or coffee. Croll painted the exterior of the chateau at night, presenting it as mystical and magical.

A painting of the chateau landscape by Carl Robert Croll

During the existence of The First Republic of Czechoslovakia, Jezeří was under the guidance of JUDr. Maxmilián Ervín Lobkowicz (1888 – 1968). Maxmilián served as a Czechoslovak diplomat and during World War II held the post of Czechoslovak Ambassador to Great Britain as he played a major role in the anti-fascist movement with the government-in-exile in London.

After he went into exile in 1938, Nazi soldiers took control of the chateau, and during 1943, a prison camp for Poles, Russians, French and out-of-favor German soldiers was situated on the property. Among the prominent figures incarcerated there was Pierre de Gaulle, brother of former French President Charles de Gaulle.

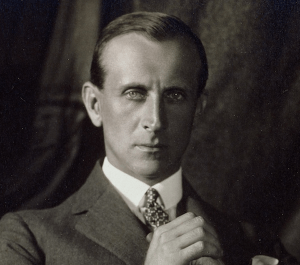

Jan Masaryk, Minister of Foreign Affairs and democrat

Maxmilián Lobkowicz returned after the war, and his good friend Jan Masaryk, then Czechoslovak Minister of Foreign Affairs, visited Maxmilián there on several occasions. However, Jan Masaryk would be shoved out a bathroom window by Communist officials at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs in Prague and fall to his death. The totalitarian regime categorized it as a suicide.

Times would change for the worst as Maxmilián and his family had to go into exile during 1948, carrying with them only a few belongings. The Communist coup had taken place, forcing the lifelong democrat Maxmilián to flee once again. At this time, the chateau was deteriorating.

Jan Masaryk, son of the first president of democratic Czechoslovakia

Jezeří certainly did not get a pretty makeover during the following decades. On the contrary, in 1950 the Czechoslovak army took over Jezeří, and the interior was destroyed. Then, five years later, the Ministry of the Interior used the building. Several other institutions were situated there in subsequent years, and times were definitely not rosy. The place was often vandalized until 1960. Jezeří Chateau became a cultural monument in 1963, though its condition did not improve. At the end of the 1960s and in the 1970s, extensive mining took place on the grounds. During the 1970s and 1980s, there was talk of tearing Jezeří down because the structure was not deemed safe due to the mining activities.

The chateau had been surrounded by intensive coal mining for centuries. Mines with dams and ditches punctuated the Ore Mountains. The mining history harkens back to the 16th century, and though it was halted for a while after the Thirty Years’ War of the 17th century, mining activities returned with a vengeance during the 19th century due to the discovery of cobalt blue and uranium in the mountains. During the first and second world war, much mining took place in the Ore Mountains. Then, after the Soviets took control of Czechoslovakia, the Ore Mountains were used as a source of uranium ore, but it was all kept hush-hush. The beautiful forests were destroyed under Communist rule. Jezeří didn’t even appear on maps anymore.

After the Velvet Revolution of 1989 that triggered the end of Communist rule, the Lobkowiczes got the chateau back in restitution. In 1991, the state declared the chateau a protected cultural monument. However, the chateau was in such bad condition that the Lobkowiczes were not able to do the necessary repairs because it would be so costly. In 1996 Martin Lobkowicz gave the chateau to the state. Repairs began, but it would be a long journey before the chateau appeared in a decent state.

The artwork in the chateau is superb.

During 1996, one room in the chateau was open to the public. When I visited in 2000, more rooms were accessible, but there was a lot of reconstruction taking place. Back then, I felt a sense of profound sadness because the necessary reconstruction would take years to accomplish. Yet hope and determination won out. The chateau continued to be painstakingly restored, and finally part of the first floor and a section of the second floor were on display for visitors. It was made a national cultural monument in 2022.

The chateau Theatre Hall

The stunning balustrade of the Theatre Hall

Now visitors can admire the renovated, lavish Theatre Hall with its original fireplace and stucco decoration. Heads of figures with various theatrical expressions decorate the walls. The cupola is impressive as is the balustrade above. Concerts are held here, reviving Jezeří’s musical tradition.

The Winter Garden today

The Winter Garden was renovated to look like it did in Carl Robert Croll’s paintings, and it is a tranquil, comfy place full of greenery. I would love to have tea in that soothing space.

Paintings throughout the chateau are intriguing with Carl Robert Croll’s works showing a stunning chateau interior and exterior at the beginning of the 19th century. Many other artworks are impressive, too. Three pianos are on display. The vaulting and stucco ornamentation in rooms is intriguing to say the least.

Jan Masaryk’s room at the chateau

Jan Masaryk’s room at the chateau

My favorite room is the one dedicated to Jan Masaryk. Seeing his room at the chateau made me imagine his visits with the Lobkowiczes during the chateau’s better days. The portraits of Jan Masaryk across from the room brought to mind Masaryk’s fierce fight for democracy and his tragic fate. I remember, during a tour of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, being shown the bathroom window from which he was shoved to the hard ground outside.

Bust of Tomáš Garrigue Masaryk, first president and Czechoslovakia and father of Jan Masaryk

Twentieth century coffee and tea set in Jan Masaryk’s room at the chateau

I see Jezeří Chateau as a symbol of hope, of the determination that can painstakingly change a monument considered for demolition into an edifice with an intriguing interior that impresses visitors. There is still much reconstruction going on, but Jezeří continues to develop – slowly but surely. I was glad I had been able to witness so many positive developments.

Handpainted toilet in the chateau

Tracy Burns is a writer, proofreader and editor in Prague.

View from the chateau