This library and art gallery in Milan is named after the patron saint of the city, Ambrose. The library harkens back to 1609, when Cardinal Federico Borromeo founded it, and the same year it opened to the public.

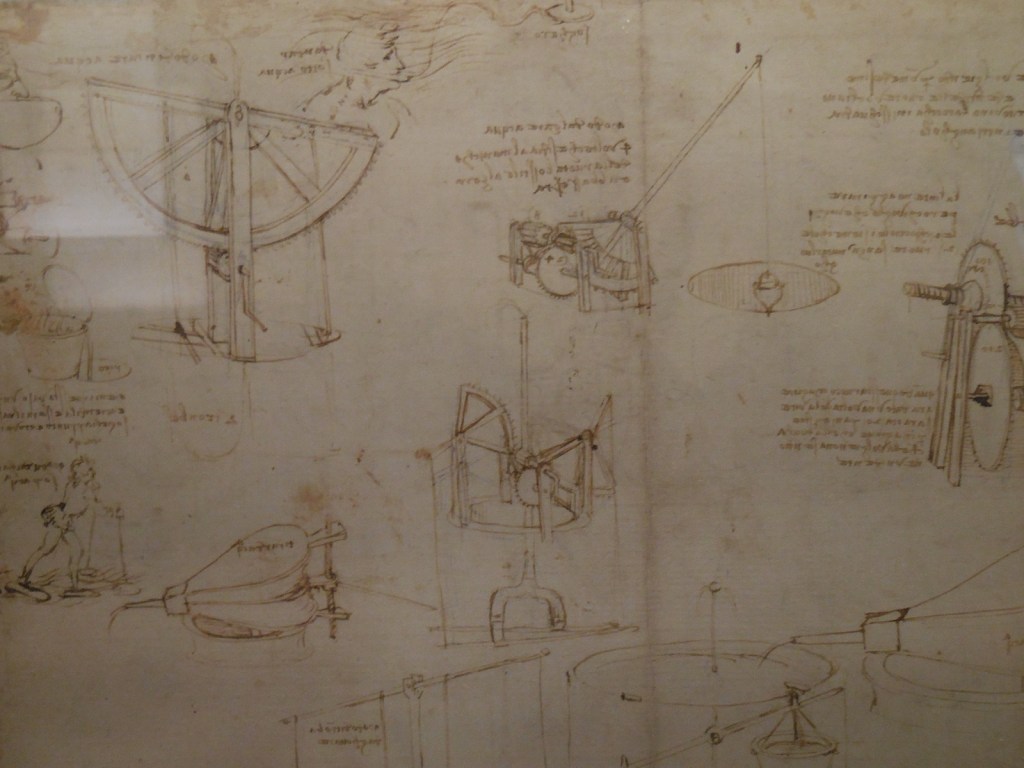

One of Leonardo da Vinci’s drawings of the Codex Atlanticus

The biblioteca houses the Codex Atlanticus by Leonardo da Vinci as well as many of his other manuscripts plus about 12,000 drawings by European artists, ranging from the 14th to 19th century. Raphael and Pisanello are represented in this collection of drawings, too. Many of its more than a million printed volumes hail from the 16th century. There are almost 40,000 manuscripts in numerous languages, including Italian, Latin, Greek and Arabic as well as some 22,000 engravings. Ancient maps, musical manuscripts and parchments also make up the collection. Some prominent guests included poet Lord Byron and novelist Mary Shelley.

Another of Leonardo’s drawings from the Codex Atlanticus

During World War II the library was damaged, and the opera libretti for La Scala Opera House were destroyed. The building was opened again in the early 1950s after undergoing renovations. More reconstruction took place in the 1990s.

When I visited, some of Leonardo’s works for the Codex Atlanticus, the largest collection of da Vinci’s drawings and writings, were on display in the library. The exhibition left me spellbound. I perused studies in aerodynamics and drawings of mechanical wings as well as various types of weapons. Leonardo rendered a large sling to throw stones and a machine to pump water from a well inside a building, for example.

I gazed upwards after studying the drawings by Leonardo, and I was filled with awe. I don’t know if I have ever seen such an incredible library. I just wanted to stand there all day, gazing at the wall-to-wall bookcases as I wondered about the titles and contents of each volume.

Established in 1618 with the collections of Cardinal Federico Borromeo, the pinacoteca was just as impressive as the library. The 24 rooms were dominated by Renaissance artworks but also boasted of renditions by 17th century Lombard artists, 18th century painters and 19th and early 20th century creators. I was especially struck by da Vinci’s 15th century “Portrait of a Musician” as it was the only portrait that he had painted. I noted the musical scroll in one hand of the sitter and was captivated by the detailed curly locks of hair, the musician’s brown eyes and his red cap.

Caravaggio’s insect-infested “Basket of Fruit” tells a story of diminishing beauty by displaying rotting fruit. Bramantino’s “Adoration of the Christ Child” shows the kneeling Bernardino of Siena, Francis of Assisi, Benedict of Nursia and the Virgin Mary making an understandable fuss over baby Jesus. I loved the angels playing musical instruments behind those figures. Emperor Augustus also makes an appearance.

Bergognone’s “Sacred Conversation” shows the Virgin Mary and Christ Child on a massive golden throne, baby Jesus on the Virgin Mary’s lap. Solemn angels flutter in the background. I was struck by the details of the Virgin Mary’s hair and by the material of the clothing worn by the Virgin Mary and baby Jesus. The two were surrounded by saints with captivating headwear, including Saint Ambrose and Saint Jerome.

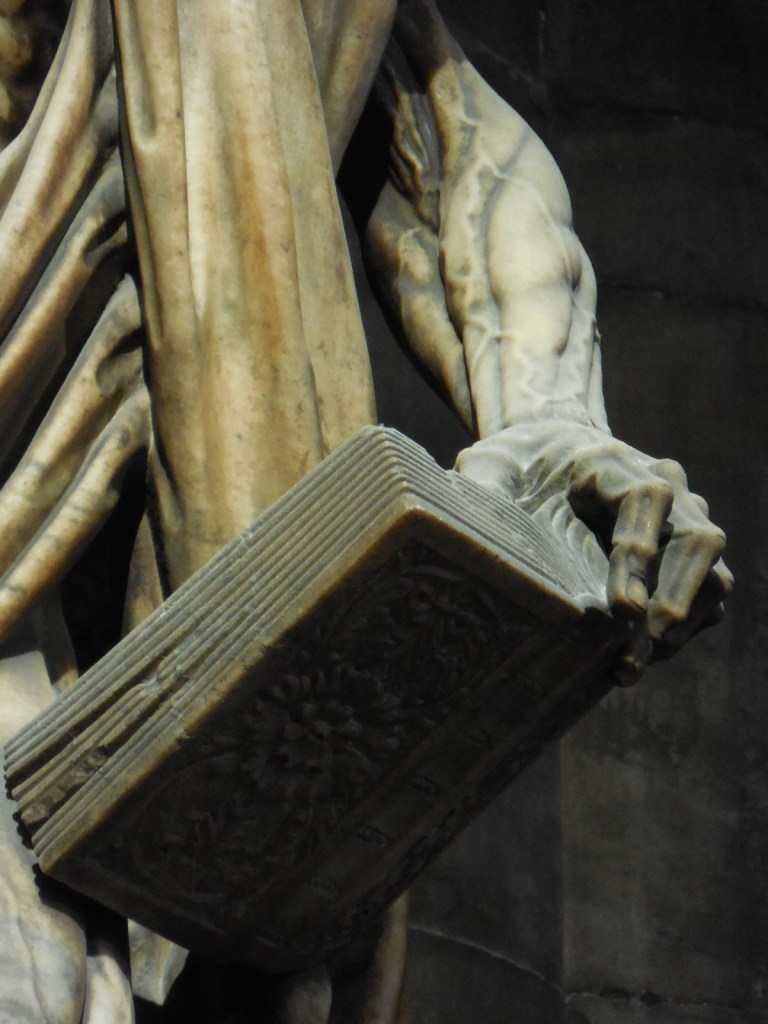

Another painting that left me speechless was Sandro Botticelli’s “The Madonna of the Pavilion.” The artist’s meticulousness was evident. The artwork shows the Virgin and Child with much symbolism. The pavilion that two angels open to reveal the Christ Child is rich in biblical meaning both in the Old and New Testament. I could almost feel the paper of the pages making up the open book in the painting.

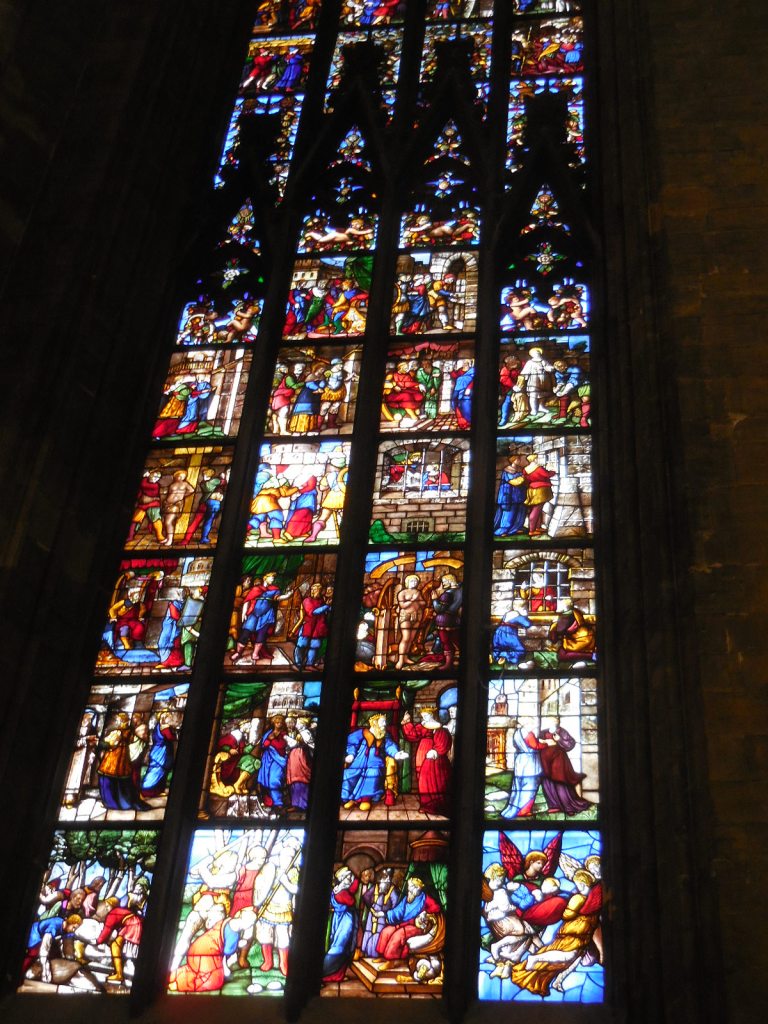

Raphael’s School of Athens

Raphael’s cartoon of the “School of Athens” is a study for the Italian Renaissance fresco painted in the early 1500s for the Raphael Rooms in the Vatican Museum. I recalled seeing the skillful rendition of philosophers and scientists from Ancient Greece at the Vatican on my 40th birthday as I mulled over the dominant role that perspective played in the artwork. Plato, Aristotle and Pythagoras appear in the fresco. Leonardo and Michelangelo are present as Plato and Heraclitus.

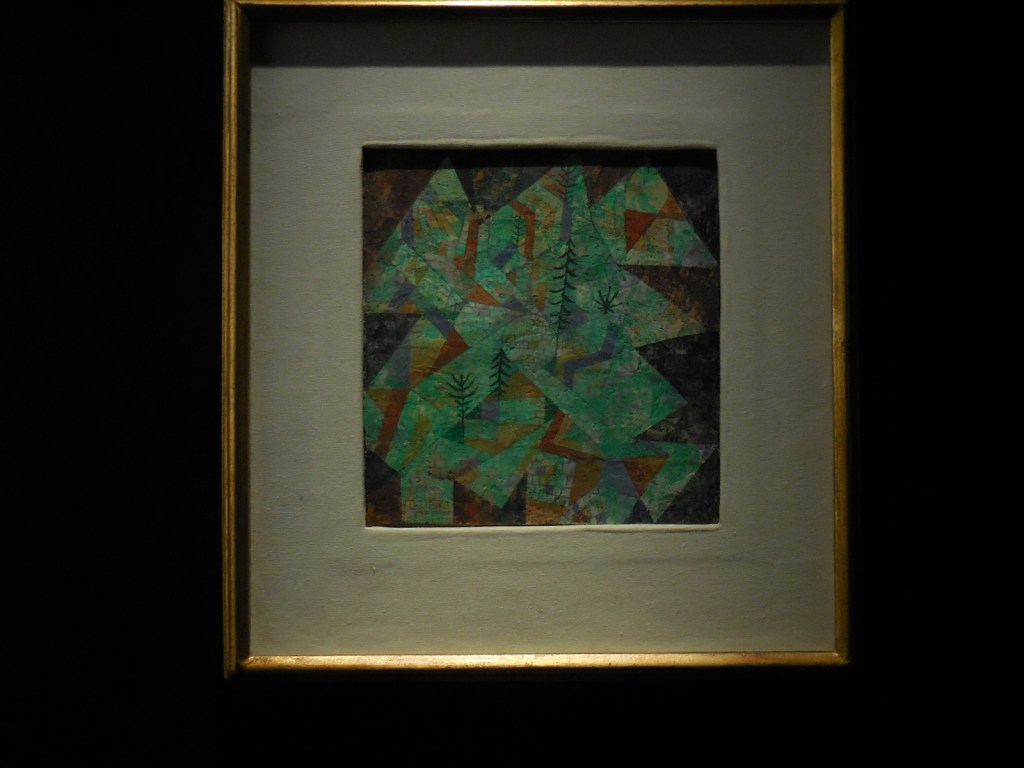

Other paintings that awed me were the fantastic landscapes of Paul Brill, whose works I had discovered some years earlier in Edinburgh. Jan Brueghel’s detailed landscapes and still lifes also are close to my heart, and I adored masterpieces from the Netherlands. I stared at these paintings, losing myself in the fantastical landscapes and details that were so masterfully rendered by both artists. I felt a special connection to these works featuring a dream-like quality as if I could be transported into a fantasy world by merely peering at the canvases.

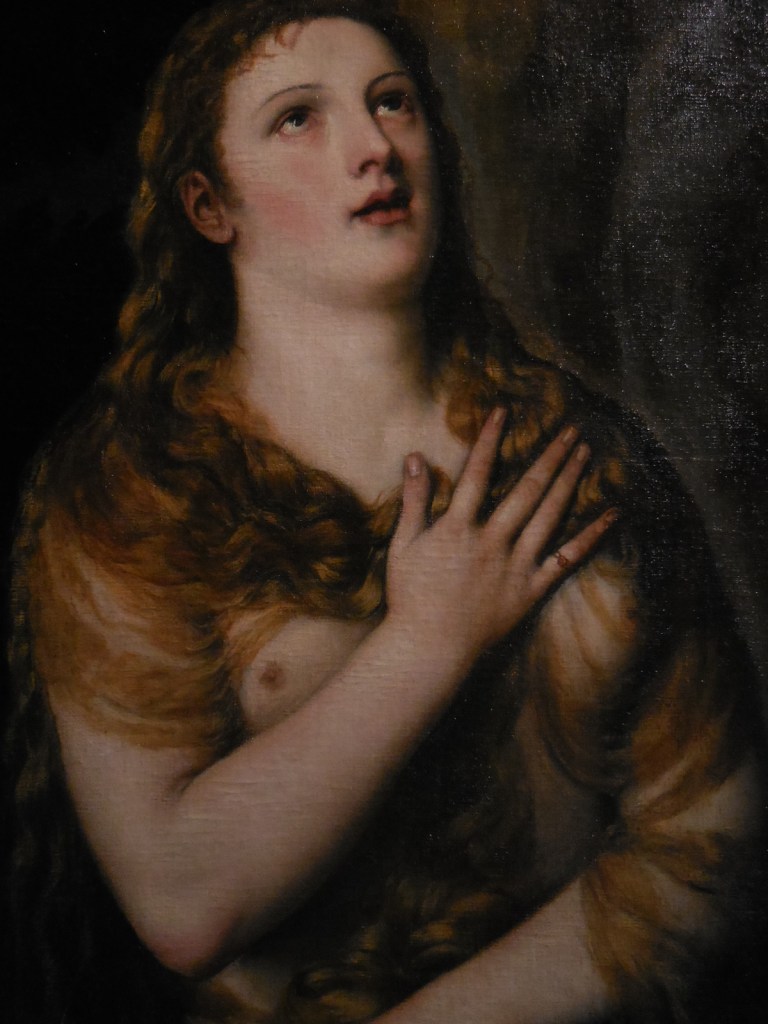

Other paintings that captured my undivided attention had been created by Bernardino Luini (I fondly recalled his paintings in Milan’s Church of Saint Maurizio), Tizian, Jacopo Bassano, Moretto and Daniele Crespi as well as Francesco Hayez, whose works I knew well from the Brera Gallery in the same city. Andrea Bianchi had created “The Last Supper,” imitating da Vinci’s masterpiece. Tizian’s “Adoration of the Magi,” Bramantino’s “Madonna of the Towers” and the locks of hair of Lucrezia Borgia all left me awe-struck.

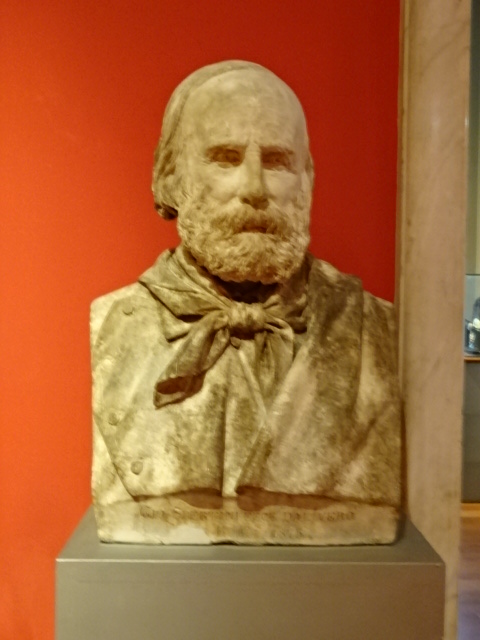

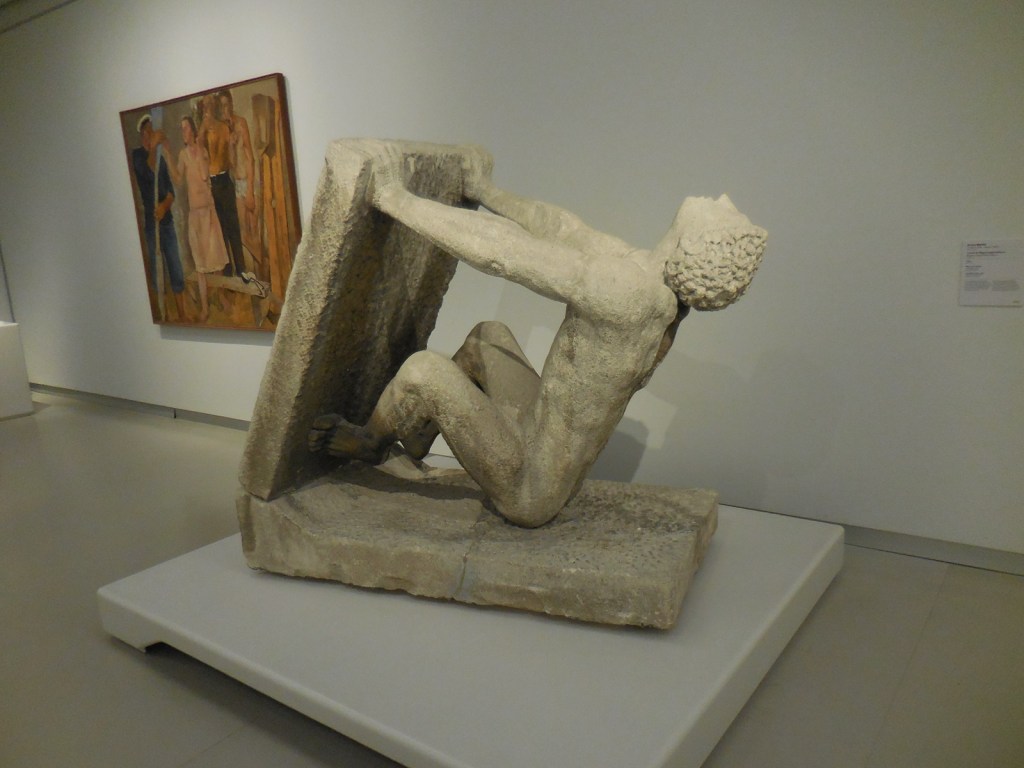

The sculptures and frescoes from the second to 16th century in the Sala del Bambaia are very noteworthy. The Hindu art of the Berger Collection captivated me. The Flemish and German painting from the 15th to 17th century enthralled. Ceramics also play an intriguing role in the collection.

I was so awed by this gallery and library that I visited it twice during my first trip to Milan. I peered at every painting and sculpture, trying to take in each artistic creation, feeling so blessed to be able to see all these masterpieces with my own eyes.

Tracy A. Burns is a writer, proofreader and editor in Prague.