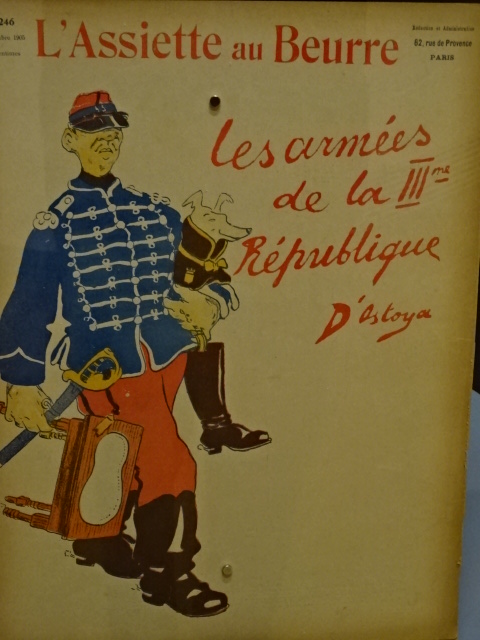

Horšovský Týn Castle and Chateau, Gothic chapel

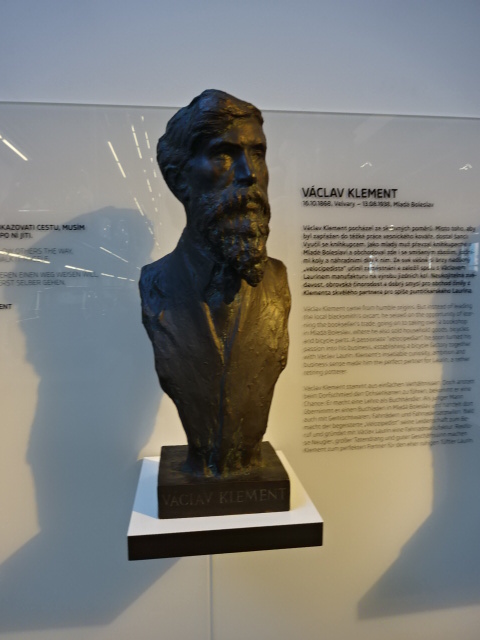

This past year marked more day trips, some with friends and others with travel agencies. Of course, chateaus were high on my list, so I will start with those.

Bečov nad Teplou Castle and Chateau, Reliquary of Saint Maurus

At Bečov nad Teplou Castle and Chateau, the group admired the reliquary of Saint Maurus, one of the most precious objects in the country. The remarkable Romanesque artifact contained the remains of saints and hailed from 1225 to 1230. Its exterior featured 12 reliefs, 14 statuettes in silver, about 200 semi-precious and precious stones, gems and other masterful goldsmith works. During World War II it was hidden under the chapel floor. The reliquary was only discovered again in the 1980s. For a long time its location was a mindboggling mystery.

Stránov Chateau

Stránov Chateau

With my best friend I visited Stránov Chateau for the first time. The Neo-Renaissance wonder featured a Gothic tower and splendid arcades in a courtyard punctuated by a beautiful fountain. The Šimonek family had lived there during the First Republic, which was the chateau’s heyday, as well as in later years, until the Communists kicked them out during 1950. They were forced to leave with only several suitcases. While there wasn’t much original furniture, the descendants had commissioned interiors that resembled those from the First Republic’s days of democratic Czechoslovakia. Seeing the chateau for the first time was exciting, to say the least.

Krásný Dvůr Chateau

Krásný Dvůr Chateau, interior

The luxury of the 18th and 19th century nobility was evident at Krásný Dvůr Chateau, partially under reconstruction when we were there on this occasion. The exquisite furnishings from 18th and 19th century periods punctuated the visit. Unique historic portraits of dogs and horses caught my attention as the horses were rendered without tails, for instance. The Meissen porcelain, gilded clocks, ancient jewel chests, decorative wall painting and various intriguing canvases in the chateau gallery all exuded the grandeur of old times. Even the upholstery of the chairs was admirable. The Černín family had this chateau designed by well-known architect František Maxmilián Kaňka from 1720 to 1724. The Černín dynasty would hold onto the chateau until World War II.

Horšovský Týn Castle and Chateau, interior

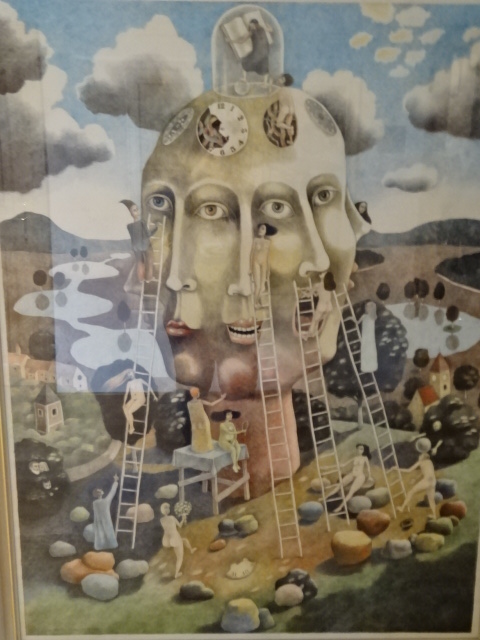

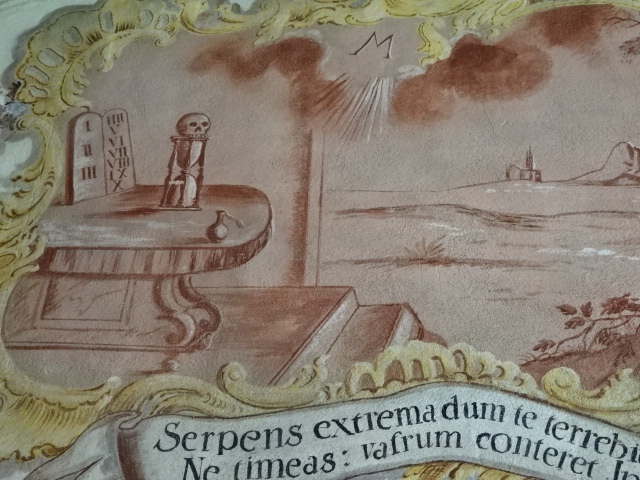

Horšovský Týn Castle and Chateau, Gothic chapel, main altarpiece

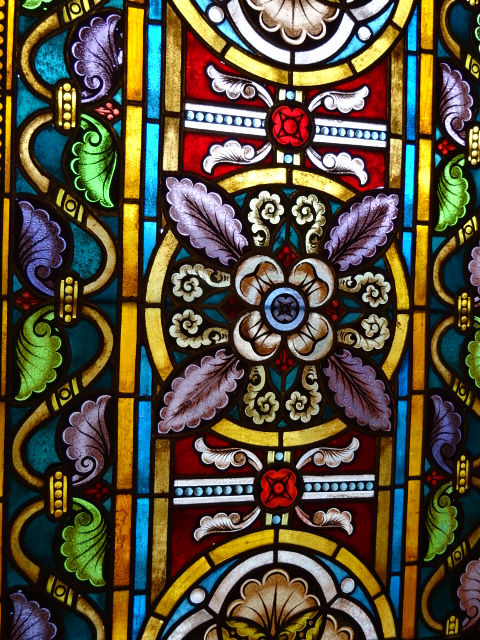

Horšovský Týn Castle and Chateau offered numerous tours. This time I went with a travel agency on one tour; in the past I had been there with my best friend on both the castle and chateau main tours. Once again, I was most impressed with the early Gothic chapel, its stunning wall painting and magnificent altarpiece. The early Gothic arch welcoming visitors to the chapel was a splendid architectural specimen. I saw much intriguing furniture from the Renaissance. A cassette ceiling hailed from the 16th century, and a superb tapestry dated from that century as well. Paintings from the Venetian School and splendid wall painting decorated another space. The Dancing Hall featured Rococo painting and a unique piano. In the Small Dining Room, I was surprised to see Edison light bulbs from 1906. The library included 15,000 volumes.

Doudleby Chateau

Doudleby Chateau

Doudleby Chateau

My good friend and I traveled with a travel agency to Častolovice and Doudleby chateaus, places to which I yearned to return for some years. Doudleby Chateau had undergone main reconstruction. It was stunning with its early Baroque wall and ceiling frescoes. Some were mythological, others religious and yet others symbolic. The lunettes of emblems with French writing were spectacular, too. I saw a parrot’s nest, flowers in a circle and a boat with a partially submerged oar, for instance. Finished in 1590, the chateau’s exterior includes unique sgraffito, open arcades and Tuscan columns. I was very impressed.

Elegant exterior of Častolovice Chateau

Častolovice Chateau exterior

The fantastic park at Častolovice Chateau

Častolovice hailed from the 13th century and boasted an extensive English park, one of the most beautiful, in my opinion. Furnishings hailed from Renaissance, Baroque, Empire and Biedermeier periods. A Renaissance cassette ceiling dated back to 1600. In the vast Knights’ Hall, I admired paintings of 24 scenes from the Old Testament. The collection of portraits showing Czech rulers was extremely impressive, too. The Renaissance arcades and distinctive fountain plus aviaries outside were noteworthy as well. There was a small zoo, but I saw an irate turkey coming my way and decided not to pay admission. The park was punctuated by peacocks and other animals as well as ponds and fantastic flora, among other attributes.

Jaroměříce Chateau interior

Interior of Jaroměřice Chateau

Jaroměřice Chateau

With a travel agency I made a very memorable trip to Jaroměřice nad Rokytnou Chateau, the biggest Baroque chateau in the country. I hadn’t been there since the late 1990s. The Ancestors’ Hall amazed with a fabulous frescoed ceiling and masterfully carved wood paneling. The ceiling and wall painting in the Ballroom was just as exquisite. The Chinese Cabinet also made a great impression.

Church of Saint Markéta, Jaroměřice

Cupola of Church of Saint Markéta

Decoration on walls of Church of Saint Markéta

Yet that was not all there was to Jaroměřice. The town had much more to offer. Nearby was the Church of Saint Markéta, measuring 450 m2 with a splendid frescoed ceiling. Pictures of the Evangelists and Roman gods decorated the walls. The main altar, celebrating Saint Markéta and the creation of light, did not disappoint, either. Our guide even played for us the impressive historic organ.

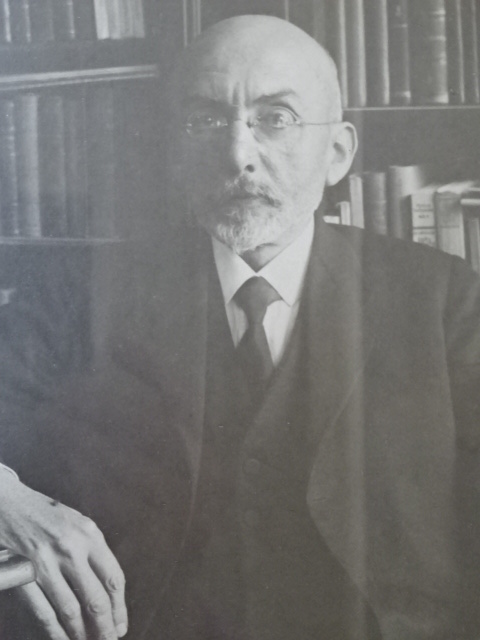

Otakar Březina

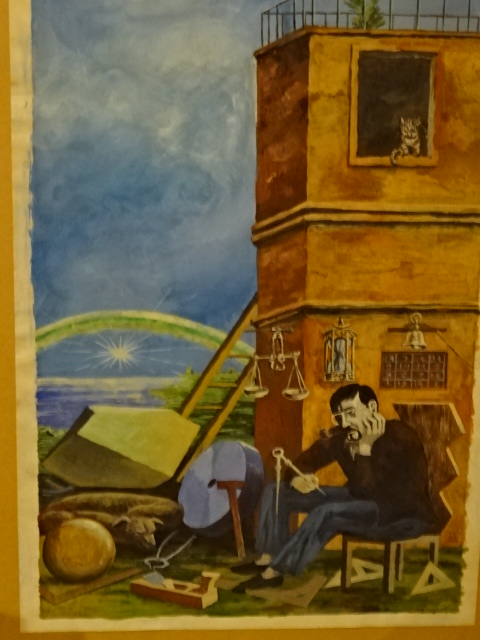

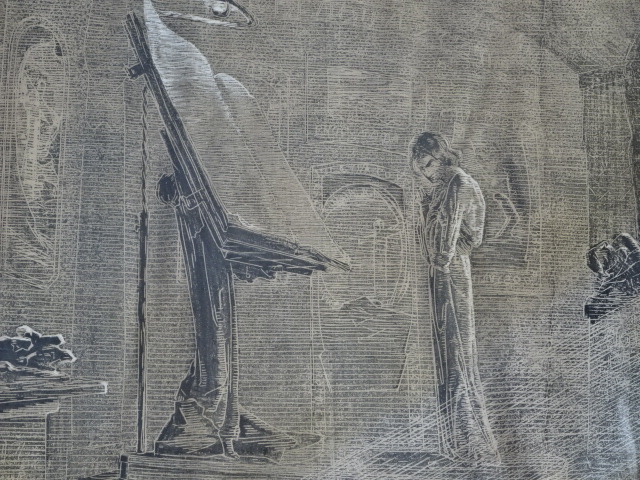

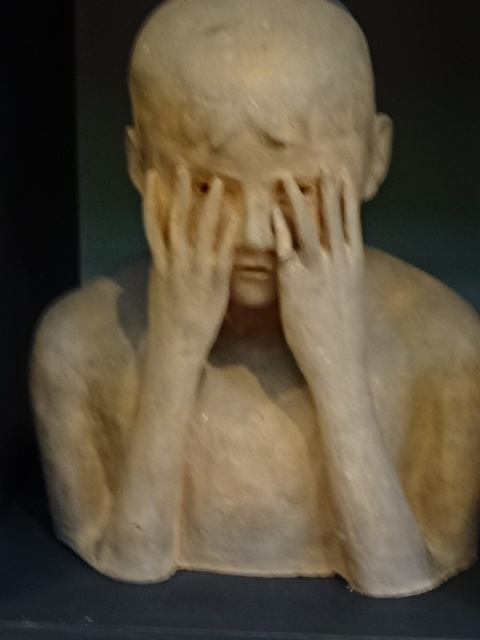

Museum of Otakar Březina, art by František Bílek

Museum of Otakar Březina

The Museum of Otakar Březina was another highlight of Jaroměřice. Březina had been a poet who was in the running for the Nobel Prize eight times. In the apartment where Březina had lived from 1913 until his death in 1929, I saw not only editions of his many books and childhood photos but also fascinating works of art by his close friend František Bílek, whose villas I had visited in Prague and in south Bohemia. Březina had promoted democracy as he had developed steadfast friendships with Czech writer Karel Čapek and President of the First Republic Tomáš G. Masaryk.

Garden of Symbols, Museum of Otakar Březina

Garden at Museum of Otakar Březina

Garden outside Museum of Otakar Březina

The garden outside the home was unique and symbolic just like Březina’s poetry. Parts of the garden were dedicated to Karel Čapek, Bílek and the most influential owner of Jaroměřice Chateau, Jan Adam Questenberk. Many flowers, plants and small trees graced the well-kept garden. One section of this Garden of Symbols represented immortality because Březina had believed that death was not an end but rather a new beginning.

Museum of Otakar Březina

Garden of Museum of Otakar Březina

Yet there was more. We visited Březina’s grave, designed by Bílek, as well as an extensive garden center established in 1901. Karel Čapek had been a devoted customer during the 1920s and 1930s. I could imagine Čapek enthusiastically picking out plants as I perused all the interesting specimens and gazed at the cats who lounged around the center without disturbing the plants.

Museum of Otakar Březina, artwork by František Bílek

Museum of Otakar Březina, art by František Bílek

With a master’s degree in Czech literature, I was always enthusiastic to learn more about Czech writers, especially poets whose works I had never read. Březina’s writing was so complex and symbolic that I had always feared I would not understand it. Visiting writers’ museums was always a big thrill for me in any country but especially in the Czech Republic. It never failed to open up new worlds.

Radim Chateau, ceiling in main hall

Radim Chateau, dining room cabinet

Radim Chateau, historical globe

Another chateau that I visited for the first time was called Radim, not far from Prague. Built in 1610, it had served as a Renaissance countryside seat of nobles, and, while it did not contain many original furnishings, the owners had amassed a great deal of impressive artifacts from various periods, especially the Renaissance. Exquisite tapestries lined a hallway. I saw a Neo-Gothic throne and an altar in the same style, both masterfully carved. Renaissance furniture also was prominent. A decorated coffered ceiling from the early 17th century and wall painting filled me with awe. The decorative main hall certainly did not disappoint.

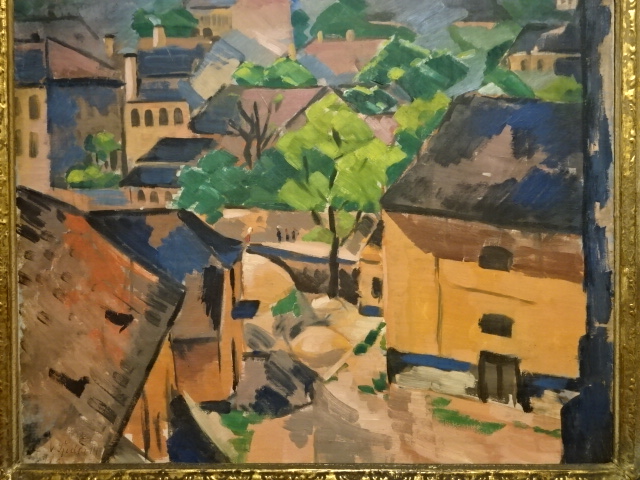

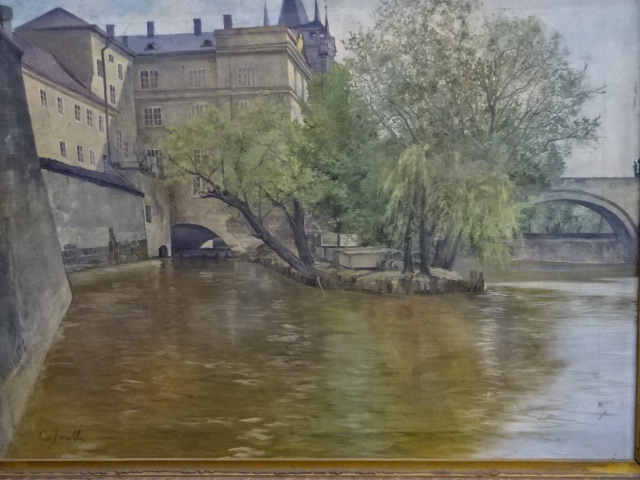

Radim Chateau art gallery, painting of Kampa Island

Painting in Radim Chateau art gallery

Radim Chateau art gallery ceiling

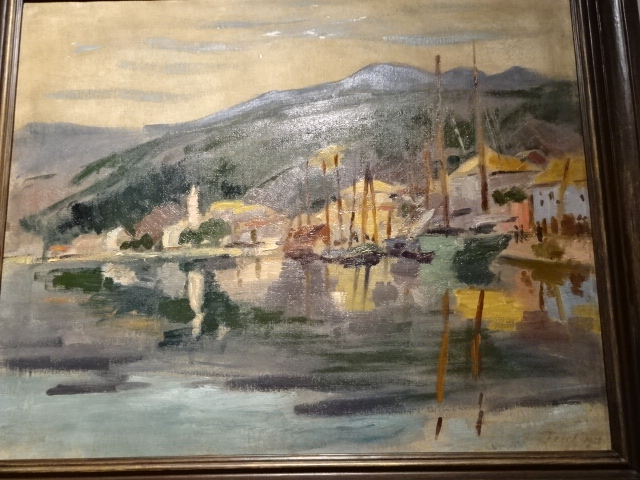

What enamored me the most about this chateau was not the first floor interior, though, but the amazing art collection the owner had put together. The owner proudly showed me his impressive collection. I saw a hallway lined with landscapes, paintings of Kampa Island and the Charles Bridge as well as the Berounka river and the Pilsen countryside region. Landscape after landscape from various parts of the country amazed me. I gazed with awe at works by Otakar Nejedlý, Vlastimil Toman, Otto Stein, Vojtěch Hyněk Popelka and many others.

Religious art in Radim Chateau gallery

Russian icon, Radim Chateau art gallery

Yet that was not all the art to be seen. In another space there was a fascinating collection of religious works, including a copy of a Titian painting and a Russian icon. Visiting Radim Chateau was a double thrill for me – I loved the furnishings and painted ceilings as well as the art gallery. The entire chateau exuded charm and splendor.

Březnice Chateau interior

Březnice Chateau ceiling

I went back to Březnice Chateau, which I had not visited for some years. The Renaissance chateau from the 16th century featured a former library with well-preserved ceiling and wall painting hailing from Renaissance days. The chateau showed off various styles – Renaissance, Baroque, Empire and Biedermeier. The Baroque chapel was stunning. The Renaissance dining room was full of historic grandeur. The armory was impressive, too.

Hluboká nad Vltavou Chateau exterior

One of my most favorites chateau was in Hluboká nad Vltavou, one of the most popular in the country, and I loved gazing at its masterful Neo-Gothic exterior. The wood-paneling with remarkable furnishings and the 57 tapestries from Brussels astounded. The library with 12,000 volumes and the armory were more than stunning. This chateau could never disappoint.

Domažlice Castle Museum, folk style wardrobe

Historical painting in Domažlice Castle Museum

I saw a castle museum in Domažlice, where I learned about the region. The other castle museum was in Kadaň, where there were displays of the history of the town and fortress-like edifice. In Domažlice the folk costumes of the area were prominently on display as were the beautiful ceramics notable for the region. Holy Roman Emperor Charles IV’s visit to Kadaň and the years the castle spent as a barracks as well as the dark Nazi period were elaborated upon during that tour.

Sculpture in Kadaň

Kadaň scenery

Yet there was more to Kadaň and Domažlice than merely their castles. We saw picturesque squares, churches, town halls, a monastery and much more in those towns. The path from the center of Kadaň to the castle was surrounded by lush flowers and plants as well as unique grotesque sandstone statues. The narrowest street in the country, Katova Street, is located in Kadaň. The monastery in Kadaň with its Gothic wall painting and other splendors was a real treat, too.

Town Hall in České Budějovice, main square

Sculpture in České Budějovice

Komerční Bank sculptural decoration

Another city sans chateau or castle that I visited was České Budějovice, one of the gems of south Bohemia for its unique and stunning architecture. Previously, I had only admired the vast main square of the city with its delightful Renaissance buildings and prominent town hall.

Former salt house in České Budějovice

Gothic wall painting in church in České Budějovice

Wall painting in church in České Budějovice

This time I saw the entire downtown area and soon learned that there was much more to the city than merely its picturesque square. The main church with Gothic (13th century) and Baroque wall painting as well as a Neo-Gothic main altar was incredible. The former salt house’s unique roof was one to remember. A large bank’s sculptural decoration was more than impressive. Other buildings were architectural gems, too. Some boasted religious paintings on the exteriors. Narrow and romantic Panská Street was another highlight of the city. The architecture throughout the city was truly breathtaking.

Firetruck museum in Constantine Spa

We also visited a small enclave called Constantine Spa. On the charming small square was a claustrophobic museum of fire trucks hailing from 1900 to 1912. Each had one ladder, and they had once been driven by horses. While it was raining during our time in the spa town, we did see some beautiful greenery as we walked to a café with delicious desserts.

Votice Monastery, town museum, painting of region

Vladimír Kaska painting in Votice Monastery

Fresco on wall and ceiling of Votice Monastery

In addition to the monastery in Kadaň, I toured two other monasteries – Votice and Teplá. Displays narrated Votice’s turbulent history during Nazism and Communism. I admired the town museum at Votice monastery. Paintings of the town in decades past caught my undivided attention. The 17th century frescoes on one wall and ceiling section at Votice were astounding. I also was amazed at the modern paintings of a local artist, Vladimír Kaska. His grotesque, playful, symbolic and colorful renditions delighted me. His works were so vibrant and dynamic. Discovering an artist whose works I did not know was one highlight of my trip there.

At Teplá Monastery

Teplá Monastery was founded in 1193, and King Václav I participated in the first mass. The Baroque church had been rebuilt in the 18th century by a prestigious architect – Kryštof Dientzenhofer. Poignant wooden statues by Ignác Platzer stood out in the church as did astounding Baroque frescoes. The church, 62.5 meters long, also featured a Rococo altar decorated with Baroque paintings.

Teplá Monastery

Still, the library that contained about 100,000 volumes in Latin, German and Czech was for me the highlight of Teplá. The two floors of masterfully carved bookcases featured an elaborate balustrade. The fabulous fresco on the ceiling represented monks and angels celebrating with religious figures, including the Evangelists. The ceiling painting was so beautiful that it almost made me dizzy with delight.

Chovojen church

Medieval wall painting in Chovojen church

I also toured a small church in Chovojen, surrounded by fields and offering a view of nearby Konopiště Chateau. The Romanesque elements of the small church were noteworthy. The rare medieval frescoes amazed me. I even saw a painting showing the medieval solar system with the Earth at the center. So many amazing artifacts located in a small church filled me with awe.

Outside altar at Holy Mountain

Holy Mountain entrance

Another religious site that I toured with my best friend was Holy Mountain, which included a church featuring a pure silver altar and nine open chapels with spectacular biblical wall and ceiling painting. The unique attraction was breathtaking. I had been there many times, but showing it to my best friend was a highlight for me.

Sculpture in garden of Janoušek studio villa

Inspired by Japanese playing cards, created by Vladimír Janoušek

I was excited to discover the studio of the Janoušek couple, 20th century artists whose workplace had been designed in the Brussels style of the 1950s and 1960s. They had used the architecturally unique studio from 1964 to 1986. In the garden stood several monumental sculptures, such as enormous figures in metal. During the tour I saw abstract sculpture from diverse periods of the artistic couple’s lives. Věra had made exquisite collages and tapestries as well as astounding sculptures of metal figures utilizing kitchen utensils and pans. Very colorful, these creations fascinated me. I had never seen anything like them.

Věra Janoušková sculpture made of kitchen utensils and pans

Věra Janoušková, tapestry

Vladimír’s work included a stunning large metal sculpture depicting the Fall of Icarus as well as a unique statue of Perseus. His combination of mythological themes and the abstract amazed me. I also was captivated by Vladimír’s creation of Japanese playing cards, so different from his monumental metal renditions. Various creations by both artists decorated shelves and showed how their styles had evolved. Panels on one wall showed photos of the two and their studio throughout the years and narrated the history of the couple’s accomplishments in a clear fashion. The studio was not without a charming library, either.

Sculpture in garden of Janoušek studio villa

I had never heard of the Janoušek artists before coming across an ad on the GoOut ticket site several months before my visit to the Smíchov house, mostly hidden from the street by garden greenery. Once again, I was excited to see an architectural wonder for the first time and learn about the couple’s unique abstract art.

Arnold Villa, reconstructed, in Brno

View from garden of Arnold Villa

Mahen Theatre in Brno

Another place I toured for the first time was the Arnold Villa in Brno, the capital of Moravia. Recently reconstructed, it hailed from 1862 and had been situated in the first colony of villas in Brno, very close to the famous Tugendhat Villa. While the original furnishings were long gone, the architect did a valiant job, including a film about the lives and times of the owners and a small collection of Jewish historical objects. Photos of the people who had lived there and in nearby villas gave the place a personal, intimate feel. While in Brno, I also toured the Mahen Theatre, the first electrified theatre in Europe. Its ceiling painting and exquisite chandelier astounded.

Kersko, sculptures of cats

My favorite restaurant, Hájenka Pivnice in Kersko

Ceramic cats made in Kersko shop I love

Of course, I visited Kersko with my best friend once again. It was one of our rituals. We ate at the rustic restaurant Hájenka, where a film based on one of Bohumil Hrabal’s books played in the background. The traditional Czech food was always delicious. We also bought coconut cookies – I hated coconut except for that in these cookies – at the local shop, which featured homemade ceramic cats inspired by legendary Czech writer Hrabal’s stray felines, revered and fed at his nearby cottage for so many decades. This wooded village brought me serenity in a poignant way that no place in Prague ever could. Hájenka was my favorite restaurant of all-time, and Kersko would always be a place close to my heart.

Interior at Přerov nad Labem architectural museum

Cottage in Přerov nad Labem museum

19th century schoolhouse in Přerov nad Labem museum

Přerov nad Labem, an open-air architectural museum, was another attraction to which I returned after many years. I admired the 18th and 19th century cottages and buildings with mannequins often dressed in the folk costumes of the eras. I loved folk style art – the furniture, ceramics and hand-painted glass as well as the clothing enamored me. It was hard to believe that so many people had lived in such small spaces. I also saw a one-room school where boys sat on one side, girls on the other. A shoemaker’s and a blacksmith’s were two other intriguing attractions.

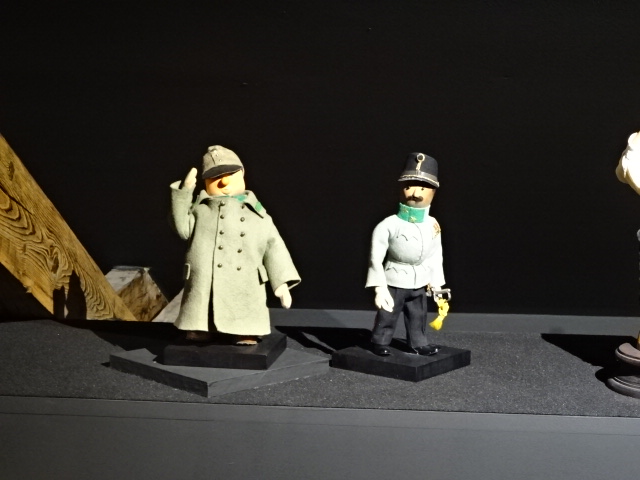

Porcelain puppet theatre at Stránov Chateau

Medieval painting at church in České Budějovice

These travels took me to places I had treasured for years and to places I was visiting for the first time. I learned about Otakar Březina and the Janoušek artists. I marveled at the Neo-Gothic exterior and exquisite furnishings of Stránov Chateau for the first time. Votice Monastery was also new to me, and I learned much about its tragic history. I hadn’t been in Kadaň before 2025 and found the town charming with many sights. I finally saw the entire center area of České Budějovice and greatly appreciated its immense beauty. I thought I had known Brno well, but I was at the Arnold Villa and inside the Mahen Theatre for the first time in my life. The Church of Saint Markéta in Jaroměřice was for me another new attraction. There were so many firsts for me this past year. I was so grateful I had discovered Radim Chateau and Stránov. I also visited the Barberini Museum in Potsdam twice, which was a first for me, though I had been in Potsdam during 1992.

Hluboká nad Vltavou Chateau, exterior

18th century tiled stove in Březnice Chateau

Returning to so many places also brought me great comfort – Hluboká nad Vltavou, Krásný Dvůr, Březnice, Teplá, Jaroměřice Chateau, Holy Mountain, Chovojen, Kersko, Častolovice, Doudleby, Přerov nad Labem, Horšovský Týn, Kersko. While I only had time to go on day trips in 2025, I was astounded, as usual, by all the sights the Czech Republic has to offer as well as three one-day trips abroad, to museums in Potsdam and Vienna. After almost 30 years here, I was still discovering new places. Going on these trips made me realize that the world, though at times cruel and ruthless, is also full of wonder and delight.

Domažlice Castle Museum folk painting

Horšovský Týn Castle and Chateau chandelier

Garden center established in 1901, cat relaxing in basket near cash register