I visited the National Museum of Science and Technology dedicated to Leonardo da Vinci on my last trip to Milan, and, quite frankly, I didn’t expect I would be too enthusiastic because neither science nor technology is my cup of tea. However, the museum was fascinating. I especially was excited by the models made from drawings of Leonardo da Vinci. They showed machines and buildings he had designed on paper as well as his version of the ideal city. I also was enthralled with the hangars containing planes, ships and trains.

Opened in 1953, the museum is one of the largest scientific and technological museums in Europe. It is located in an ancient monastery not far from the Chiesa di Santa Maria delle Grazie, where I had seen Da Vinci’s Last Supper. Covering science and technology in Italy from the 19th century to the present, the museum holds the biggest collections of models of machines from designs by Leonardo da Vinci found anywhere. It includes 2,500 pictures, designs, sculptures, medals and artistic objects. There are seven sections, including materials, energy, communication, transport, food and science for young people as well as the Leonardo da Vinci Art and Science department. Musical instruments, clocks and jewelry are on display in this part.

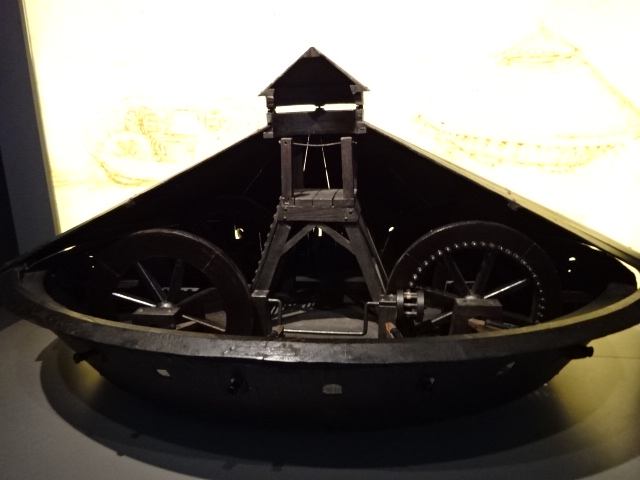

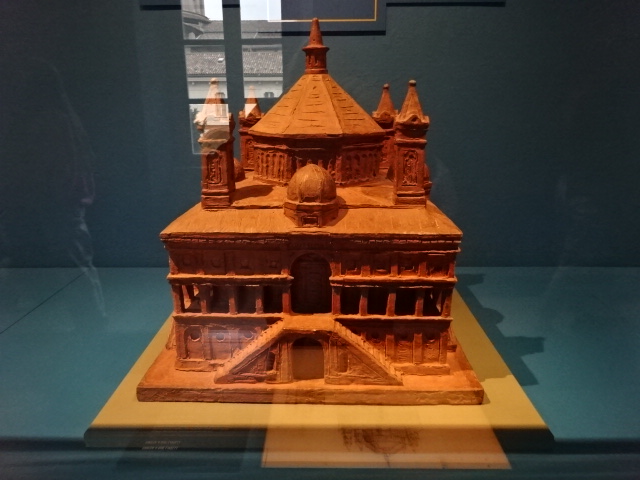

The Leonardo da Vinci galleries display 170 military and civilian models, pieces of art and other objects. The models of buildings based on his drawings are architectural gems. Machines made from his drawings also impressed me. I saw a hydraulic saw, a flying machine and a spinning machine, for instance. I was awed with Da Vinci’s vast knowledge of anatomy, physics, mathematics, botany, geology and cartography.

The transport department includes air, rail and water. The trains are located in a pavilion originally built for the 1906 Expo. A façade resembling a 19th century structure has been added to the historic building. One train that caught my attention was the GR 552 036 locomotive from 1900. It had towed the Indian Mail train from Bardonecchia to Brindisi on its journey from London to Bombay. A horse-powered omnibus from 1885 was another delight.

One of the top exhibits is the submarine S 506 Enrico Toti, the first submarine to be constructed in Italy after World War II. It began operation in 1968 and was roaming the seas for 30 years. During the Cold War, it searched for Soviet submarines.

The Vega Launcher from 2012 is a model of the first Vega made by the European Space Agency. It has a height of 30 meters and weighs 37 tons. The Vega can release satellites that weigh up to 2,000 kilograms.

The ships also intrigued me. One of the largest ships in the museum, the Ebe Schooner from 1921 was initially used by merchants to transport their wares through the Mediterranean. In the 1950s it became a training ship. The ballroom and bridge of the Conte Biancamano ocean liner also are worth seeing. They date from 1925. It has traveled extensively, making the journey from Genoa to Naples to New York and also going to South America and the Far East. During World War II it was used by American soldiers.

The planes were enthralling. I especially liked the Macchi MC 205 V from 1943. It made a name for itself during World War II. The plane has two machine guns and two cannons. Modern military planes and a modern helicopter also are on display.

Enrico Forlanini’s experimental helicopter from 1877 has the distinction of being the first object to fly. Pilotless, it has a steam engine and two counter-rotating propellors. During its flight, the helicopter rose about 13 meters and stayed in the air for 20 seconds. It also made an impressive landing.

I saw other intriguing exhibits. The Regina Margherita Thermoelectric plant had once provided lighting plus electrical power for 1,800 looms. Even King Umberto I and Margherita of Savoy were present for the opening ceremony. It hails from 1895.

Computers made up a significant part of the collections. I saw the Olivetti Programma 101 from the 1960s, the first personal computer. It was a programmable calculator that was small enough to fit on a desk. NASA utilized this contraption for calculating the Moon landing.

Space is another theme on which the museum focuses. I saw a moonrock that is 3.7 billion years old. Astronauts on Apollo 17 brought it back to Earth in 1972. Another exhibit showed space coveralls from 2014 and 2019. Astronomy plays a role, too. Two 17th century globes and telescopes are on display. Giovanni Schiaparelli used a telescope made in 1866 to study the surface of Mars. Schiaparelli peered through another telescope, this one hailing from 1774, when he discovered the asteroid 69 Hesperia and was able to describe what goes on with falling stars.

The diverse exhibits were a big thrill to see. I was so surprised that I had been so interested in the museum. Unfortunately, it was very crowded, so I didn’t get to peruse everything as well as I would have liked. The museum was definitely a popular destination for tourists and Milan dwellers alike. I could certainly understand why.

Tracy A. Burns is a writer, proofreader and editor in Prague.