The second Sucharda Villa

I had waited months for the tour of Stanislav Sucharda’s second villa. The first time I had had to cancel due to illness. I had seen the exterior of the Sucharda Villa on Slavíčkova Street for the first time on a tour of Bubeneč in Prague’s sixth district. Constructed for sculptor, designer and medallist Stanislav Sucharda from 1904 to 1907 by architect Jan Kotěra, the villa is shaped like a cube and features a mansard roof, polygonal bay windows and half-timbered gables. To say I was impressed is an understatement.

The studio of the Sucharda Villa, now a separate building

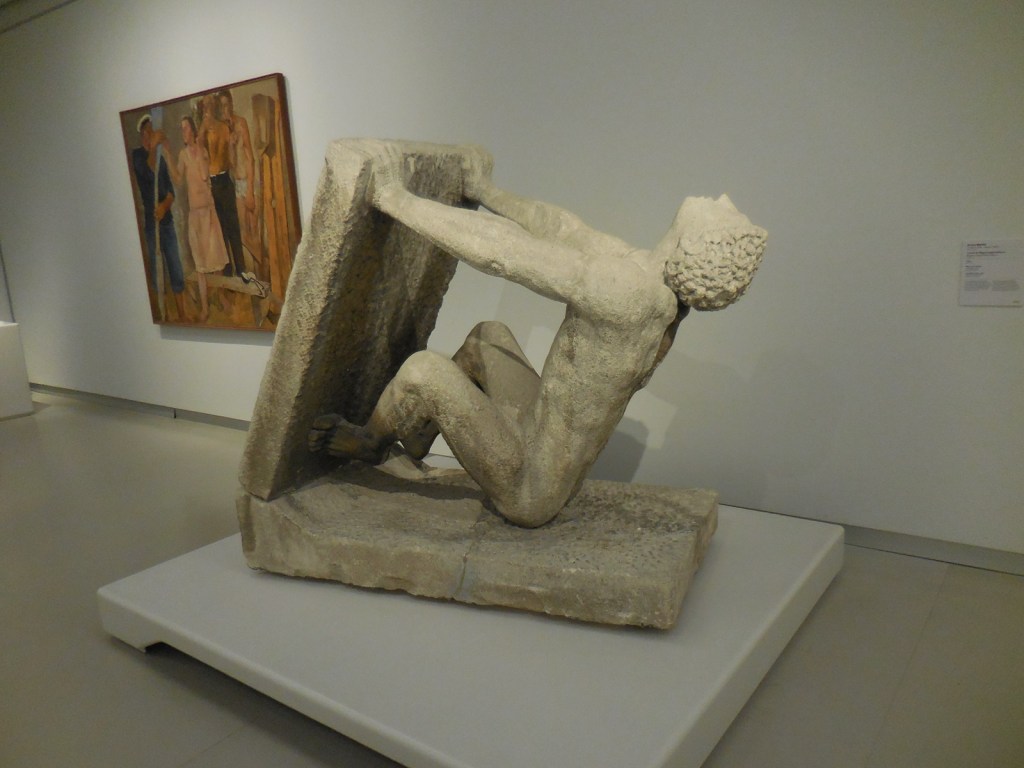

A large studio building, influenced by Cubism, stood next to what was Sucharda’s second villa. A knight figure is featured on its steep roof. This had once been Sucharda’s atelier but now was owned by the government for administrative purposes. Sucharda had needed a large studio after he won the competition for the colossal monument to František Palacký, the founder of Czech historiography as well as a prominent politician. Palacký’s nickname was the Father of the Nation.

Jan Kotěra – Photo from Kralovehradecký architektonický manual

Kotěra received accolades not only as an architect but also as a theoretician of architecture, a furniture designer and a painter. He designed all the interior furnishings for this villa. I was familiar with Kotěra’s National Building in Prostějov, Moravia. The two-winged, L-shaped building in Prostějov was clearly divided into sections for a hall, restaurant and cafes. Kotěra had also designed half of the complex for the Law Faculty of what is now Charles University, which I had often passed on foot or on the tram.

Decoration on Sucharda’s first villa

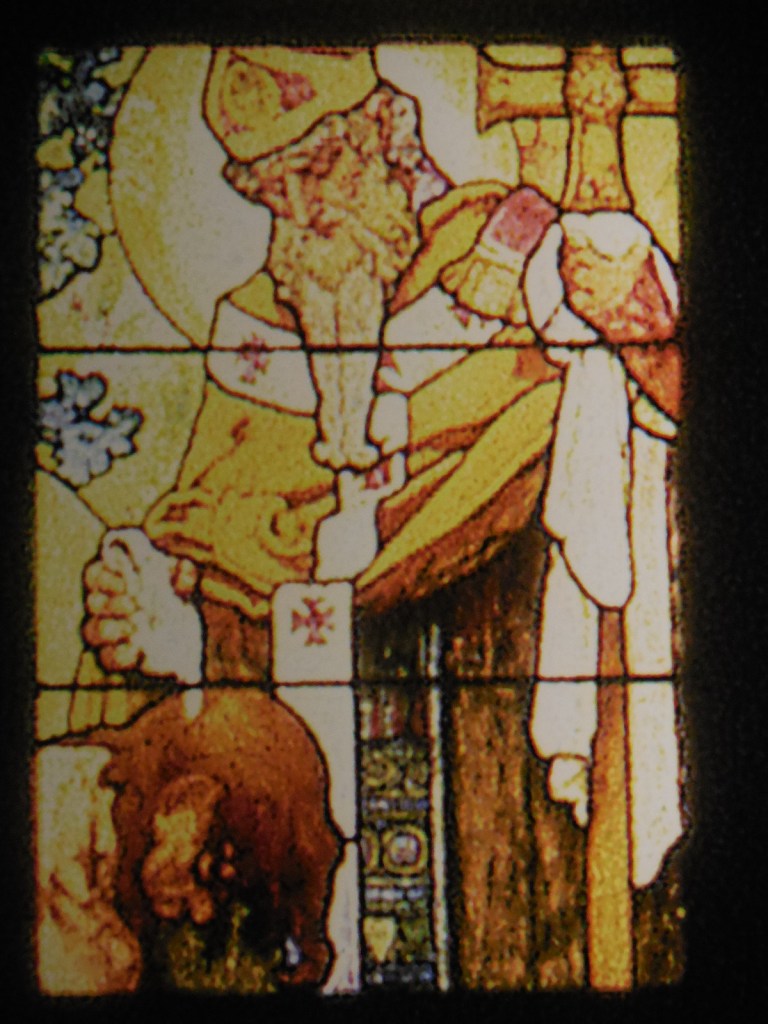

As I have already pointed out, this was Sucharda’s second villa in Bubeneč. The first one is also on Slavíčkova Street. It is a neo-Renaissance structure that he and his family had inhabited for 10 years. An exquisite painting of the bishop Božetěch is featured on the exterior of this villa. Stanislav sold this building to his brother Vojtěch, who had made a name for himself as an artist, too.

Mašek’s Villa on Slavíčková Street

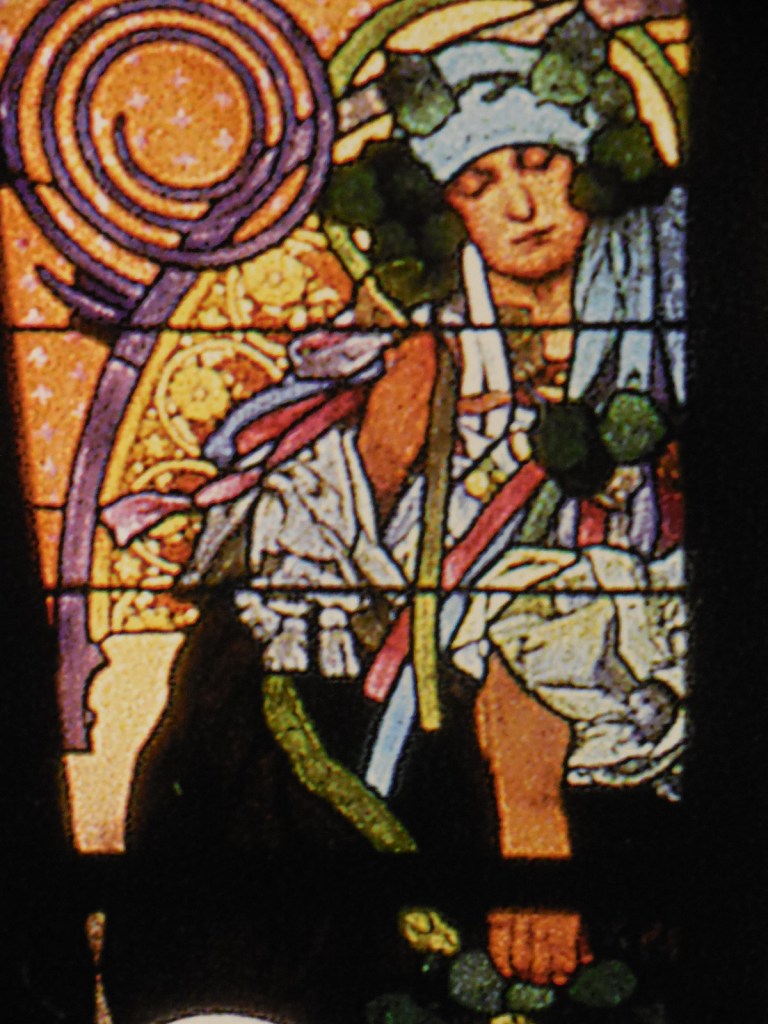

Indeed, Slavíčkova Street is dotted with villas built for artists, including architect Jan Koula and painter Karel Vítězslav Mašek. The prominent villas on this street were built from 1895 to 1907. On Mašek’s villa there is floral decoration with a painting of the Virgin Mary with Child. Both the Koula and Mašek villas feature motifs of white pigeons. The painting on one side of Koula’s villa is outstanding.

Koula’s Villa on Slavíčkova Street

Back to Stanislav Sucharda: Family members have taken up artistic professions for at least 250 years. Stanislav was brought up in Nová Paka, where his father, Antonín Sucharda, had created and restored sculptures. The five children helped out in their father’s workshop and would continue to pursue artistic careers.

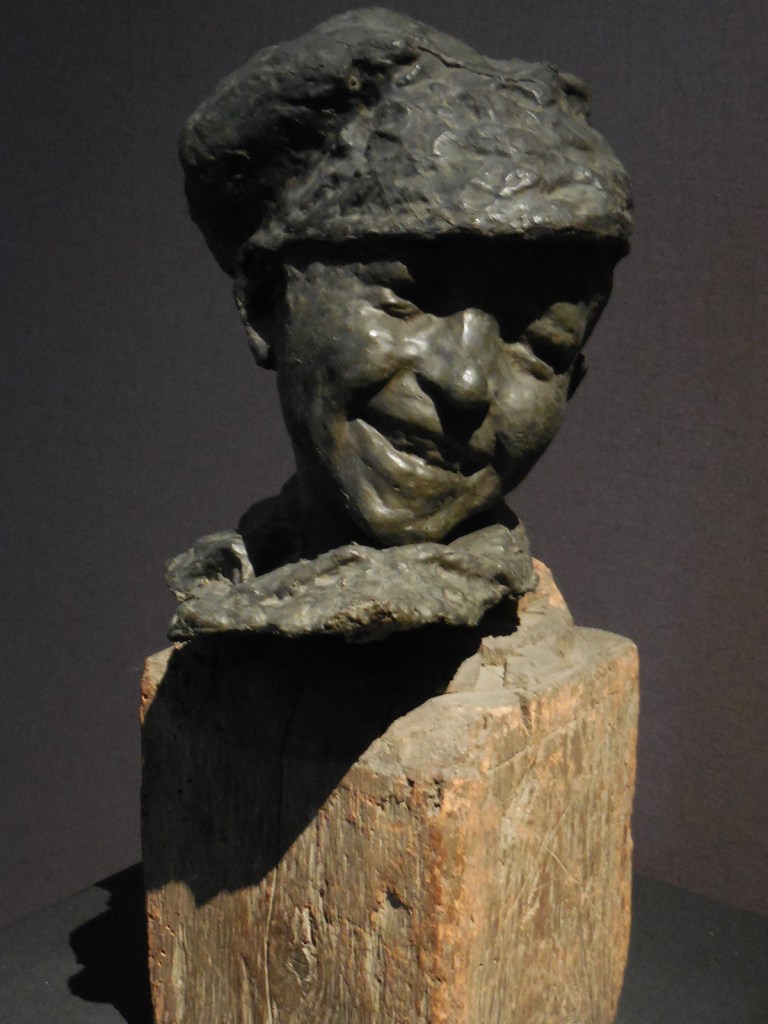

Stanislav Sucharda

Stanislav attended the School of Decorative Arts in Prague, where he studied under the greatest Czech sculptor of the 19th and 20th century, Josef Václav Myslbek. Every Praguer knows Myslbek’s equestrian statue of Saint Wenceslas at the top of Wenceslas Square. I vividly remember the statue being decorated with votive candles and pictures of Václav Havel shortly after the former president and former dissident died in 2011. The sight had made an unforgettable impression of me and filled me with an immense feeling of loss. Many demonstrations have taken place around the statue, too, even under Communism.

Bust of František Palacký from Maleč Chateau, where Palacky had resided.

Myslbek had been very influenced by the Czech National Revival that promoted Czech culture and the Czech language. I was familiar with Myslbek’s sculptural portrait of František Palacký, who had supported the Czech National Revival, on Palacký’s former home in the street named after him.

Postcard of Sucharda’s Prague and Vltava (1902) printed by Museum of Stanislav Sucharda

It is not surprising that Sucharda’s early creations were greatly influenced by Myslbek’s realism. Sucharda became known for his creations of Czech historical figures and the Slavonic themes in his work, which are two of the reasons his works appeal to me. I love Czech history and studied it in graduate school. After a Prague exhibition of Auguste Rodin’s sculpture in 1902, however, Sucharda’s style became more vibrant and underwent some changes.

Postcard of Sucharda’s Liliana (1909), printed by Museum of Stanislav Sucharda

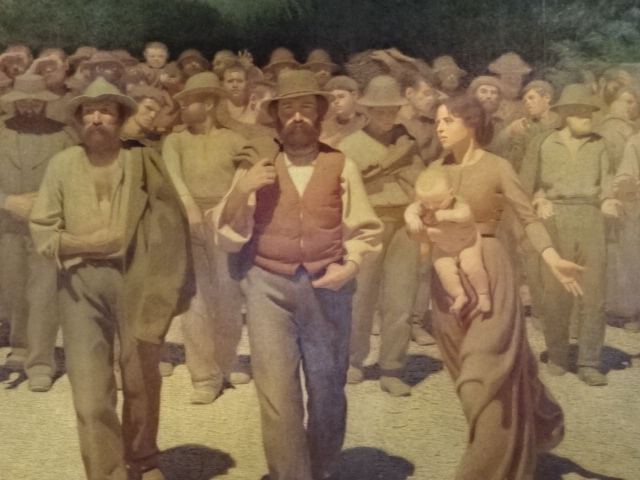

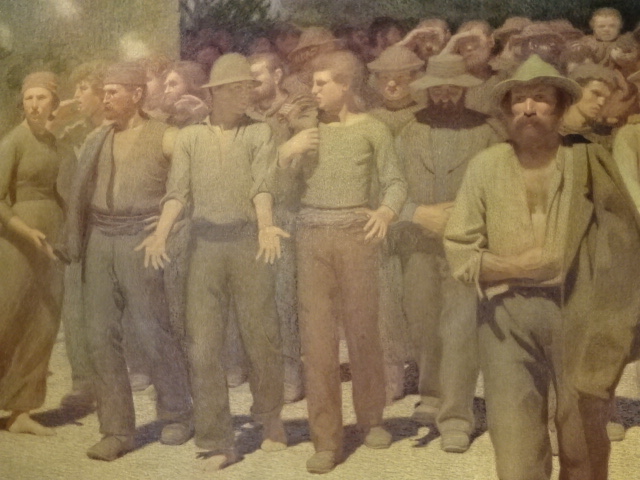

Sucharda is best known for his sculptural grouping of the monument to Palacký on Palacký Square in Prague’s second district. Many years ago, Palacký’s statue had greeted me every time I took the Metro at the square or rode by on a tram. I had become very interested in Palacký’s work during graduate studies in Czech history, and I found that having a monument dedicated to him near my apartment was refreshing and soothing. The bronze statues of the monument brought to mind the revitalization of Czech history and culture during the Czech National Revival.

Palacký monument on Palacký Square in Prague

The monument also made me think of the Czech nation finally gaining independence after World War I with the creation of Czechoslovakia, even though Palacký had not been alive to see that. I thought of the Czech nation breaking free from the Germanization of the Austro-Hungarian Empire whenever I passed by that sculptural grouping.

A cast of Palacký’s hand by Myslbek

In the same district as his villa, Sucharda had created a monument to composer Karel Bendl. He also built monuments to Czech historical figures Jan Amos Komenský (Comenius in English) and martyr Jan Hus, for instance. Other designs include sculpture for the study of the mayor of Prague from 1907 to 1909.

Sucharda also authored many reliefs, medals and plaques, and his medal designs were highly praised. His medal works even received international recognition. Stanislav became professor of the first Department of Medal Design of the Academy of Fine Arts in Prague after spending two decades as a professor at the School of Decorative Arts. He had also served for seven years as the chairperson of the Mánes Union of Fine Arts, which organized many influential exhibitions in Prague and was an important promoter of modern art.

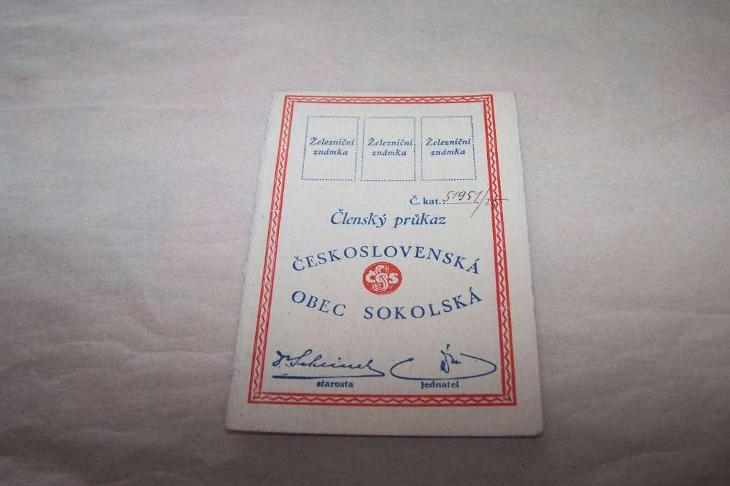

Sokol membership card from 1912. Photo from aukro.cz

For Sucharda there was more to life than artistry. He was an avid member of the legendary Sokol physical education organization, even working as an instructor there. His entire family was involved with this prominent Czech organization.

Then fate intervened. Stanislav served in the military during World War I and did battle on the eastern front. Wounded in the war, he died after returning to the Czech lands in 1916, a year after being chosen to head the medal design department of the Academy of Fine Arts. I thought it was such a shame that he did not get to see the establishment of independent Czechoslovakia with Tomáš Garrigue Masaryk at the helm.

Sucharda’s Second Villa as seen from the garden

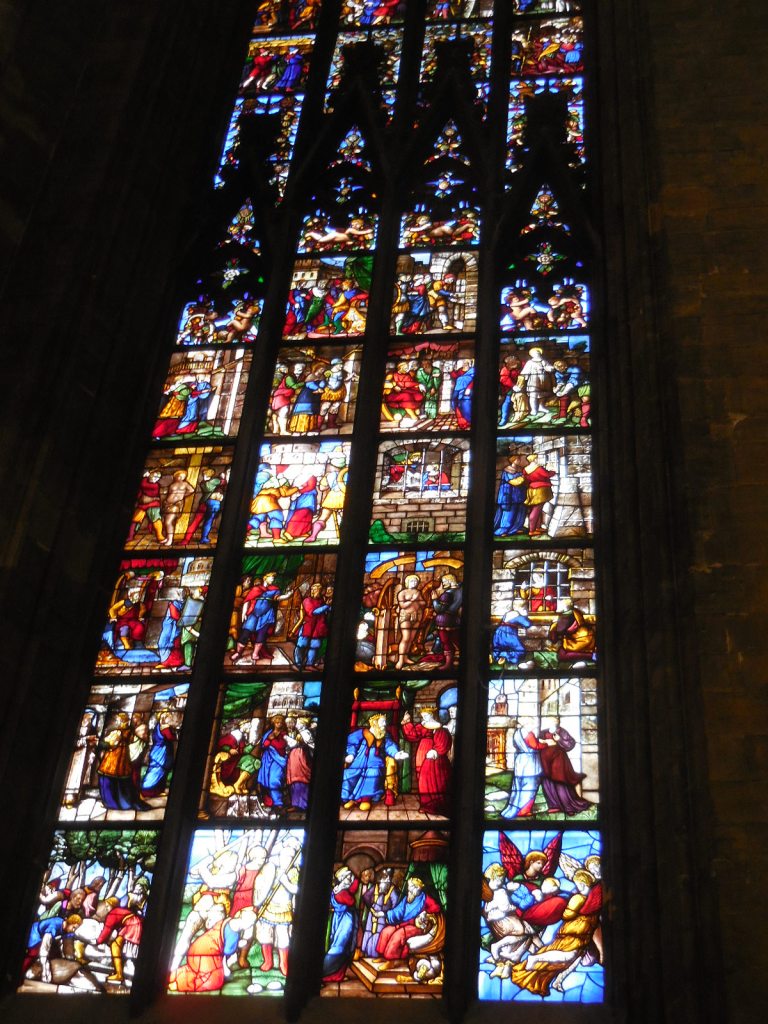

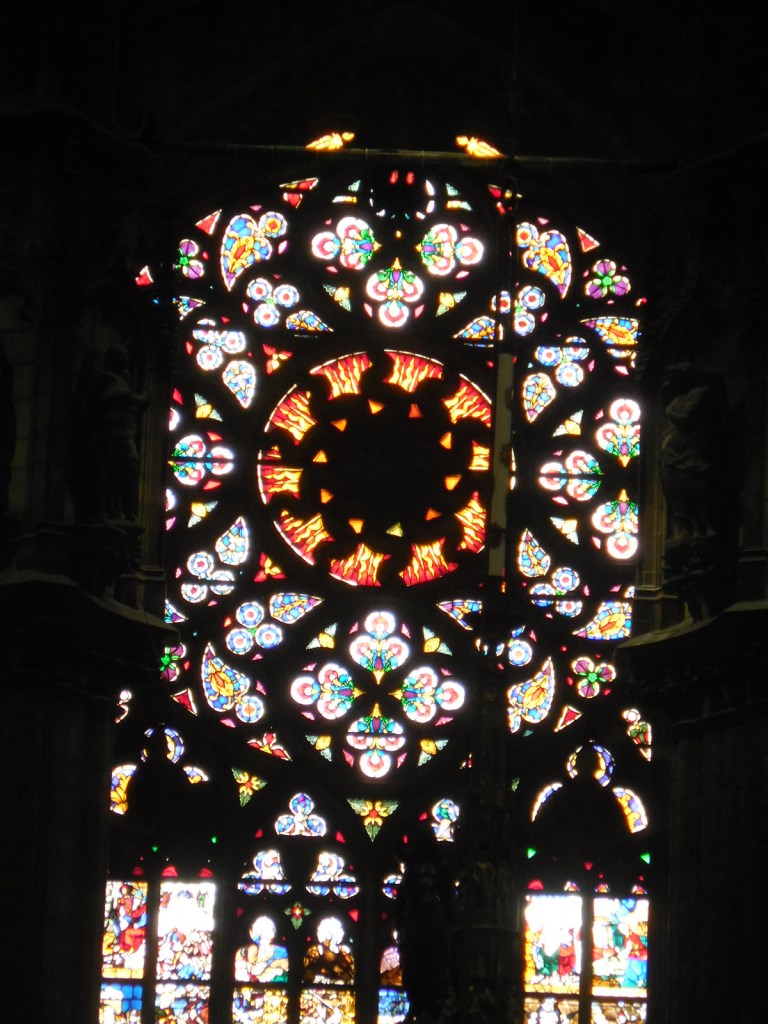

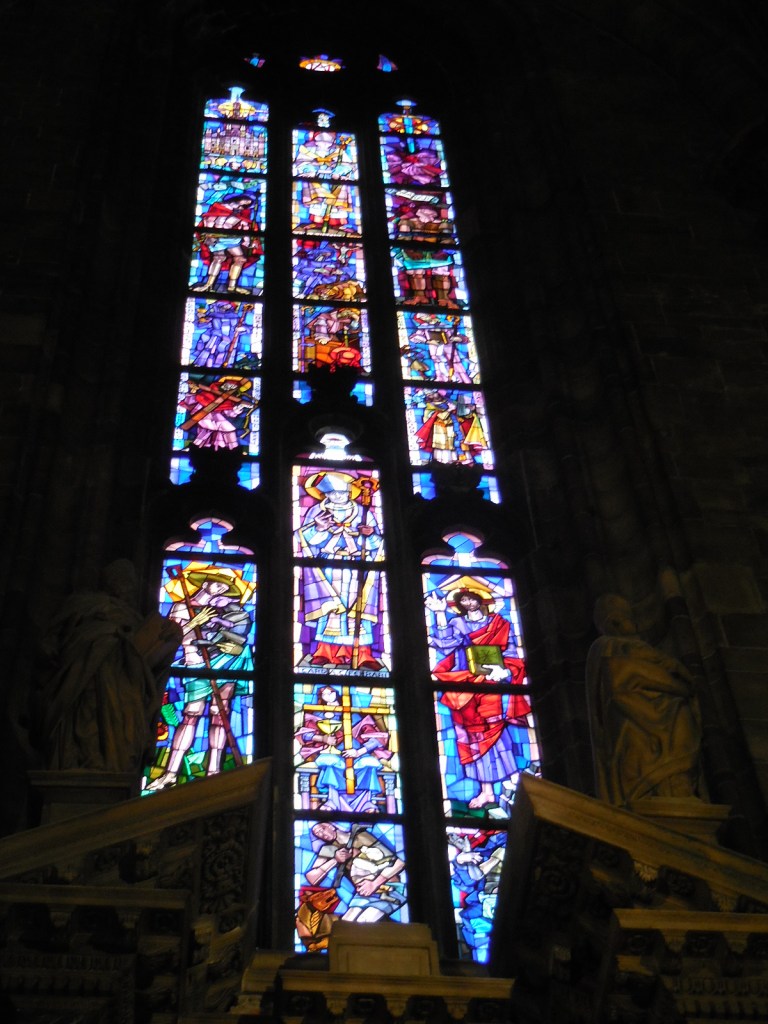

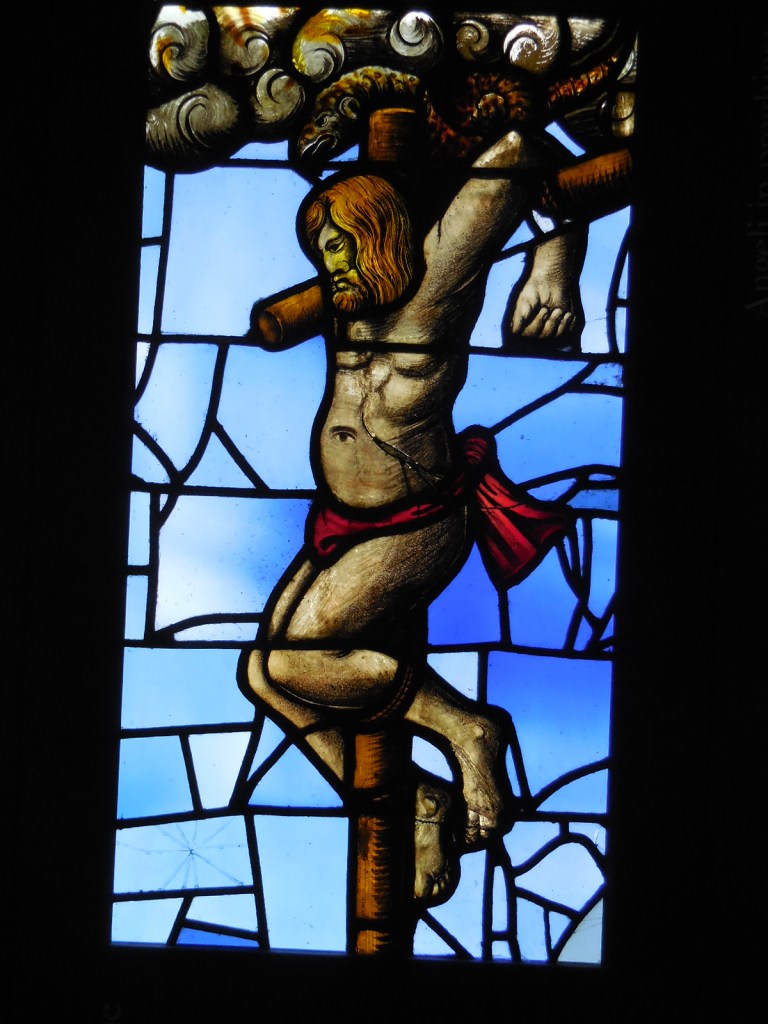

The tour of the two-story villa was very impressive as Sucharda’s granddaughter told the group about her father’s work, the pieces of art in the building and the history of the villa. A professional guide was insightful, too. The interior consisted of an English style hall with stained glass decoration on high windows and sculptures, reliefs and paintings. The British architecture of the hall reminded me a bit of Staircase Hall in the Moravian villa of Slovak architect Dušan Jurkovič, who had been inspired by the English Arts and Crafts movement.

Jurkovič’s Villa in Moravia

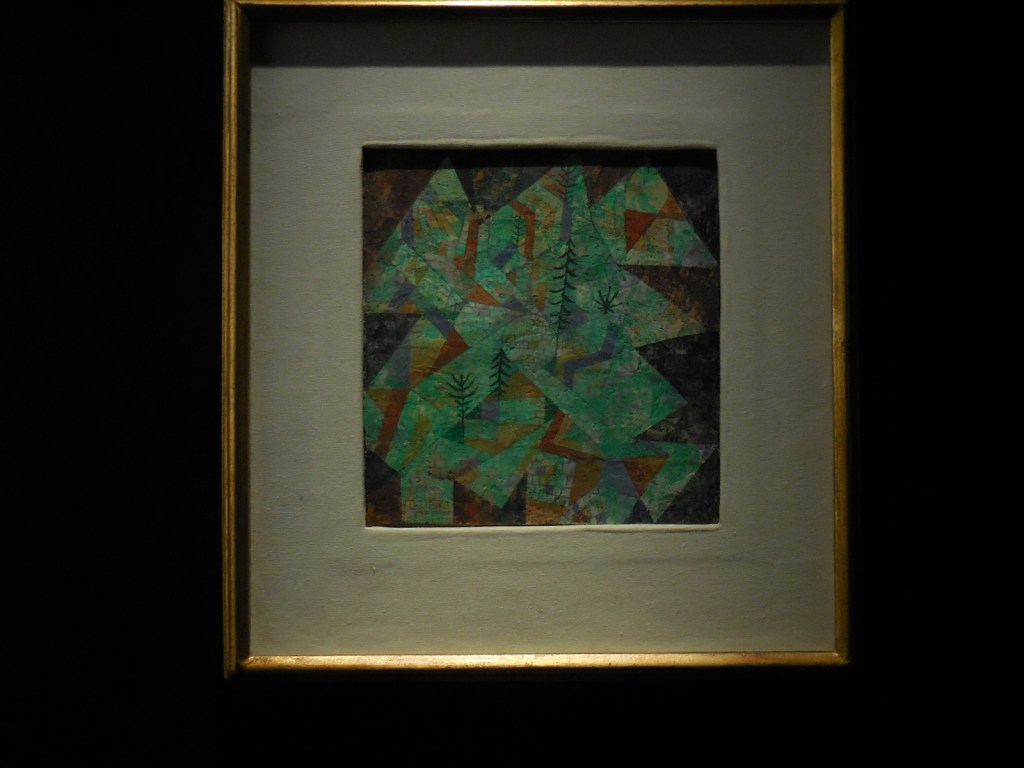

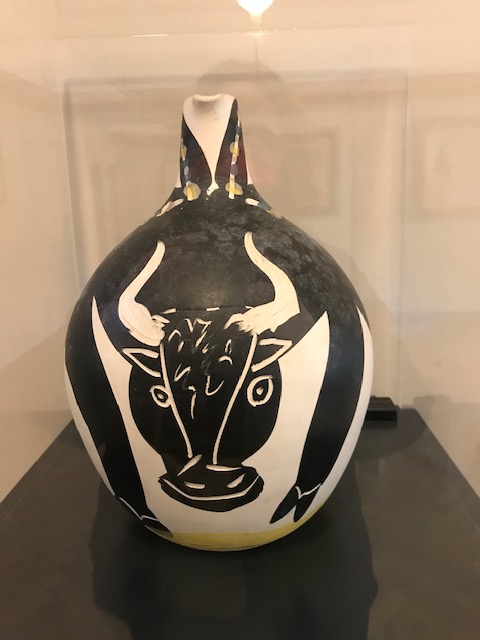

We saw works by Edvard Munch and Rodin as well as many Czech creations. Small statues and other artworks decorated the top of an elegant decorative fireplace. Behind plush red seating shaped in a semi-circle was a beautiful stained glass window. I especially liked a large relief by Sucharda in the entrance hall and a life-size statue.

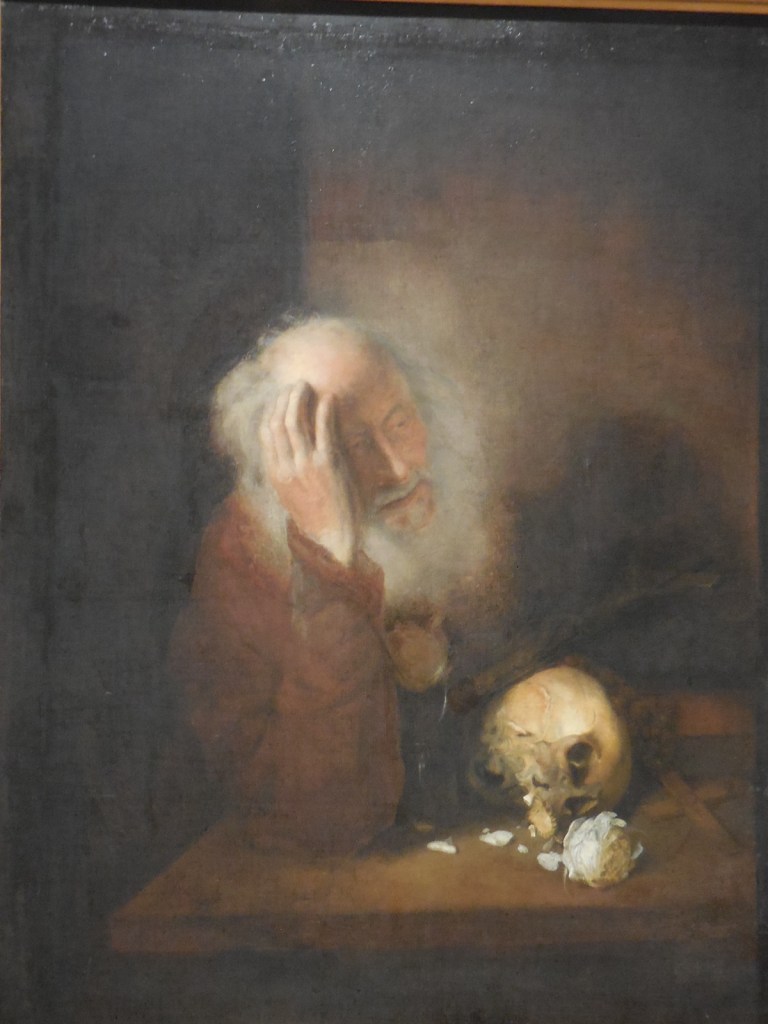

In the narrow hallway there was a fountain with sculptural decoration that employed religious motifs. We also saw the dining room with its paintings, statues, busts and ceramics. Works by Stanislav’s daughter were very impressive. The woodcarving of Kotěra furnishings was masterful. A small conservatory was adjoined to the dining room. Intriguing artifacts decorated the piano, and outstanding paintings decorated the walls. I especially liked a rendition of the Roman Forum by Cyril Bouda. It brought to mind my passion for Italy and the time I had showed my parents the Roman Forum

The garden had an intimate feel. I could imagine sitting there, reading a good book and relaxing on a sunny day.

The Muller Villa in Prague

Visiting villas in Prague was one of my favorite pastimes. I recalled touring the František Bílek Villa, the Muller Villa, the Winternitz Villa and the Rothmayer Villa in the capital city. I had also toured several intriguing villas in Brno and the Bauer Villa in central Bohemia. I would definitely recommend touring these villas. I was glad I was able to get to know Stanislav Sucharda better via his villa and the art within it. I developed a much stronger appreciation of Sucharda’s contribution to modern art. The tour was even more impressive than I had imagined it would be.

Tracy A. Burns is a writer, proofreader and editor in Prague.