Amalfi Coast

Amalfi Coast

This past year’s travels included two trips to Italy, one to my beloved Milan and environs and the other to the Amalfi Coast, somewhere I have dreamed of going for many years. I also spent time visiting sights in the Czech Republic, such as Zbiroh and Karlova Koruna chateaus and the towns of Kutná hora and Hradec Králové. I also dined in the traditional Czech pub Hájenka in Kersko. I flew to northern Virginia to see my parents for two weeks in March and had a great time with them as well as with four friends. In Washington, D.C., I visited the National Portrait Gallery and Museum of American Art.

From Petr Brandl Exhibition

I saw many thrilling art exhibitions, including ones focused on the Baroque art of Petr Brandl and the Art Nouveau works of Alphonse Mucha. Karel Teige, Czech avant-garde artist best known for his interwar works, was the focus of an exhibition at the Museum of Czech Literature, which I visited for the first time in 2023.

Campari Tomb at Monumental Cemetery in Milan

My May trip to Italy last year saw me back in Milan, which I had visited for the first time the previous year. I went to several sights I had not seen before. I toured Milan’s Monumental Cemetery to see the architectural gems of tombstones in various styles from the 18th century to contemporary. A colossal sculptural grouping of Da Vinci’s The Last Supper, made for the Campari family, was my favorite. I also saw a structure resembling the Tower of Babel and another looking like Trajan’s Column. An Egyptian pyramid shape made up another monument. Another artistic delight was Italian artist Lucio Fontana’s design of a modern angel. The sculptural decoration throughout the cemetery was astounding.

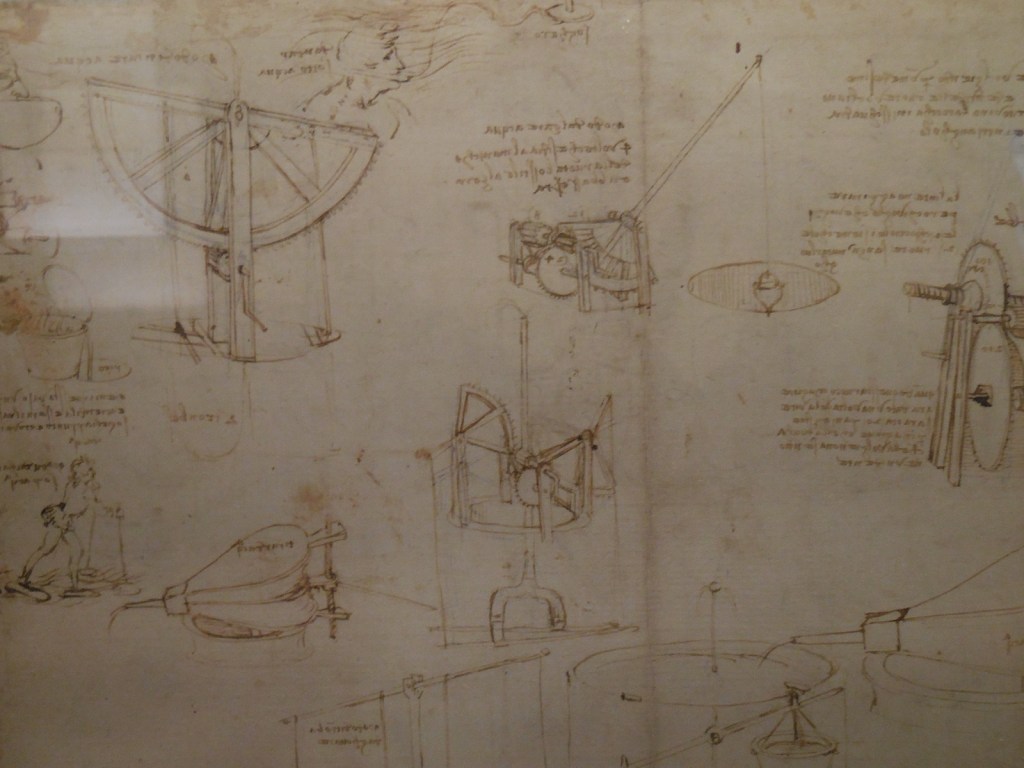

At National Museum of Science and Technology Leonardo da Vinci in Milan

I also visited the National Museum of Science and Technology Leonardo da Vinci, where I was enamored by the 170 models of Da Vinci’s drawings of buildings, machines and weaponry. I also loved the hangars featuring planes, ships and trains. A Vega Launcher hailed from 2012. A submarine also stood outside.

Paintings lined the walls at the House Museum of Boschi Da Stefano in Milan.

The House Museum of Boschi Da Stefano, located in a posh apartment outside the city center, featured 300 works of 20th century art, mostly paintings but also drawings, furniture and sculpture. Most pieces hailed from 1900 to 1960. The walls were covered with art from top to bottom. Some artists represented were Fontana, Giorgio De Chirico, Pablo Picasso and Amadeo Modigliani.

Navigli section of Milan

I also visited the Navigli district of Milan, where two picturesque streets flanked a canal, making for a picturesque setting. The Navigli is dotted with outdoor cafes and stores, including a few intriguing bookshops.

Basilica of Saint Anastasia, Verona

I spent time outside of Milan, too. I traveled to Verona for the second time. I marveled at the Basilica of Saint Anastasia, the largest church in the city as well as the cathedral and three museums – the Castelvecchio Museum, the modern art museum and the House Museum Palace Maffei – my favorite. The Basilica of Saint Anastasia was built in the 13th century and boasted a Late Gothic façade. The main altar was made from light yellow marble while one chapel housed a famous 15th century fresco. Red and white marble columns decorated the interior. The Pelligrini Chapel included a fresco from the 14th and 15th century as well as intriguing sculpture. A fresco at the left transept had been rendered by a disciple of Giotto. A rudder of a 16th century ship added to the splendid interior decoration.

Verona, House Museum Palace Maffei

Verona, House Museum Palace Maffei

However, it was the House Museum Palace Maffei that captured my heart. Half of the Palace Maffei was designed as a luxurious home punctuated by art from various eras ranging from the 14th century to modern day. The other half was a 20th century art gallery, featuring works by Picasso, Duchamp, De Chirico, Warhol, Ernst, Modigliani, Fontana and others. Paintings, sculpture, drawings, engravings, pottery, bronzes, frescoes and furniture of both Italian and foreign origin dazzled my mind.

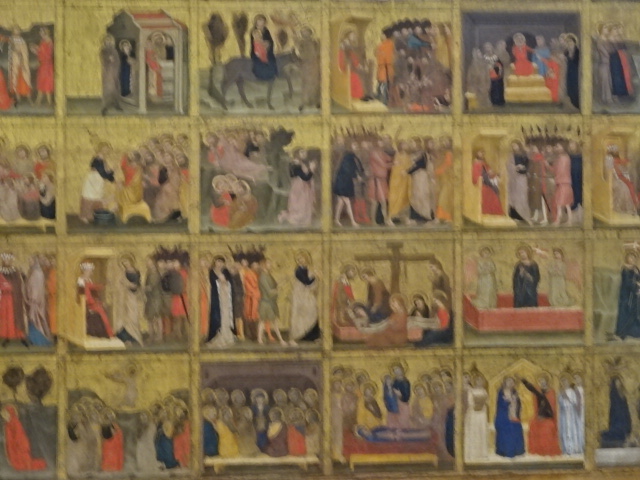

In the Castelvecchio Museum, Verona

The Castelvecchio Museum, established in the 14th century, included 30 halls of Italian and European painting and sculpture from the Romanesque days to the 1700s. Not only did I see many paintings but also ancient weapons, ceramics, gold objects and more. The exterior featured panoramic views of the romantic city.

A romantic lane in Bellagio

My other day trip was to Lake Como, where I visited picturesque Como, Bellagio and Mennagio. Unfortunately, it rained all day, but I still had a great time. I also saw the exterior of some noteworthy villas, such as Richard Branson’s waterfront home, the Villa Carlotta and a villa where some episodes of Succession had been filmed. I saw a hotel where Greta Garbo had acted, too. The Villa Olmo in Como had a neoclassical exterior and stunning lake views. Bellagio featured steep, cobblestoned lanes and the Romanesque Basilica of San Giacomo. Mennagio was home to several intriguing churches and had a picturesque lakefront square.

House Museum Bagatti Valsecchi, Milan

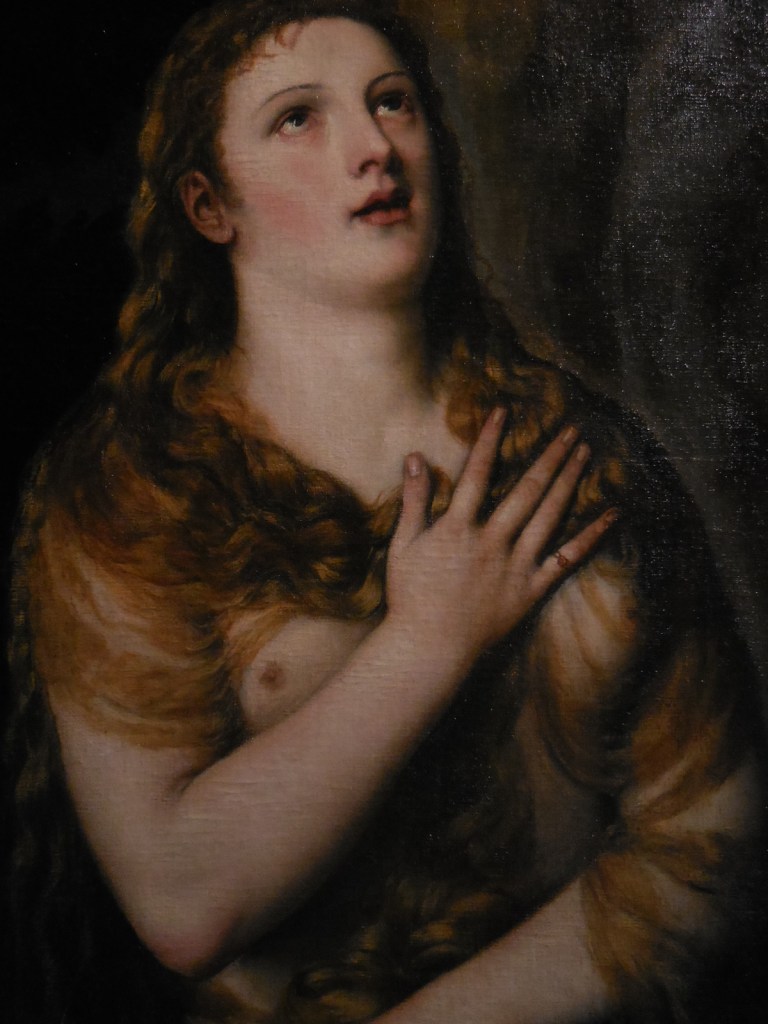

House Museum Poldi Pezzoli, Milan

In Milan I also visited beloved sights that I had first seen the previous year. I returned to the House Museum Bagatti Valsecchi with its Renaissance and Neo-Renaissance art and to the House Museum Poldi Pezzoli with its art of various eras, such as medieval triptychs, ceramics, historical pocket watches and other time pieces.

Gallery of Modern Art, Milan

Gallery of Modern Art, Milan

I visited the second floor of the Gallery of Modern Art with its Grassi and Vismara Collections. The Grassi Collection featured both Italian and foreign works ranging from the 14th century to contemporary times. Oriental art was displayed, too. The Vismara Collection concentrated on 20th century masterpieces. On that floor I saw impressive art by Manet, Picasso, Gauguin, Renoir, Van Gogh and Cezanne. Toulouse Lautrec was well-represented, too.

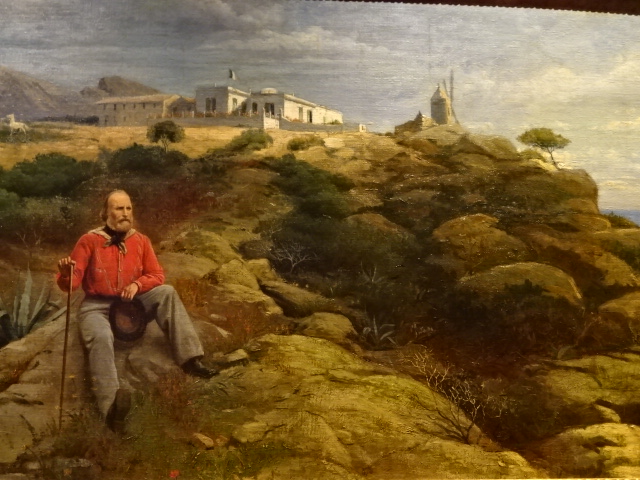

Museum of the Risorgimento, Milan

Brera Art Gallery, Milan, Work of Andrea Mantegna

The Museum of Risorgimento remains another of my favorites with its painting, prints, sculptures and artifacts depicting Italian historical events from 1796 to 1870. The Brera Art Gallery was another highlight, as I gawked at the Italian art from the 13th to 20th century as well as at the foreign works in the 38 vast halls. I loved the paintings from the Netherlands, including those by Peter Paul Rubens and Jacob Jordaens. Other Brera-represented artists dear to my heart included Francesco Hayez, Andrea Montegna, Tintoretto and Caravaggio. I even visited an exhibition of ancient manuscripts in the historical Baroque library. Once again, I was amazed by the 16th century frescoes by Bernardino Luini, his brothers and his son in the Renaissance Church of San Maurizio in downtown Milan.

Sorrento, Nativity Scene, Cathedral of Saints Filippo and Giacomo

During my trip with arsviva travel agency to the Amalfi Coast in June, I fell in love with Sorrento. The streets were picturesque, and the Cathedral of Saints Filippo and Giacomo was Romanesque with a Neo-Gothic façade. Three lunettes showed off beautiful frescoes while a rose window also astounded. Inside, the Latin cross interior boasted three naves with 14 pilasters. The pulpit, hailing from the 16th century, had Doric columns. Stunning frescoes on the cupola, intarsia adornment and a Baroque ceiling were other remarkable elements. The Chapel of Nativity displayed a Neapolitan Nativity scene from the 17th century.

Correale Museum, Sorrento

Museum of Intarsia, Sorrento

The Correale Museum served as a provincial art gallery, and I was enthralled by the 17th and 18th century Italian landscapes, especially those of Castellammare di Stabia, where we were staying. Greek and Roman fragments, historical furniture, clocks, ceramics and porcelain were also on display. The waterfront boasted spectacular views of the sea, which were very soothing. The highlight of my visit to Sorrento was the Museum of Intarsia, with everything from music stands to large beds showing off intarsia decoration by local artists. Some historical paintings were also on display. Downstairs, I saw the innovative, avantgarde designs of contemporary intarsia artwork.

Pompei

I also visited Pompei for a second time. Even though the day was scorching hot, I enjoyed seeing the small and big theatre, the basilica and three temples, especially the one named after Apollo with its 48 Ionic columns. The amphitheatre with a capacity of 20,000 spectators also caught my undivided attention. The wall paintings and mosaic floors of what had been luxurious homes were sights to behold as well.

Ravello, pulpit in cathedral

We moved to a nice hotel in the picturesque, tranquil town of Maiori, where I could spend time in a café or restaurant overlooking the beach or savor homemade ice cream. The town that had made it on UNESCO’s list during 1997 was a perfect place to relax after a busy day out. Before arriving at our hotel in Maiori, we saw Ravello’s Romanesque Cathedral of Saint Maria Assunta and Saint Panteleone, hailing from the 11th century. I admired the 12th century bronze doors and remarkable 13th century Pulpit of Gospels adorned with mosaics. One 16th century chapel contained an phial of blood of Saint Panteleone. The views of the sea from the hilly town were spectacular, too. Numerous famous guests, from Richard Wagner to Virginia Woolf and Greta Garbo, had graced the streets of this town.

Ravello Cathedral, bronze doors of central portal

Positano, a UNESCO-listed tourist site since 1997, was a picturesque hillside town, but, unfortunately, during this past June, it was much too crowded to enjoy. I did peek into the church, though. Its main altar showed off a Byzantine icon from the 13th century. The views of the sea were fabulous.

Cathedral of Saint Andrew, Amalfi

Cathedral of Saint Andrew, Amalfi

Another highlight of my trip was visiting the Cathedral of Saint Andrew in Amalfi, which was founded in the ninth century AD and boasted a 13th century Arab-Norman exterior with Italian Neo-Gothic elements. The mosaic adornment in the tympanum is stunning. Sixty-two steep steps led to the bronze doors of the central portal that hailed from Constantinople, made in the 11th century. A cloister included some intriguing fragments of wall paintings while the interior had Baroque features along with Gothic and Renaissance chapels. The Basilica of the Crucifix harkened back to the ninth century and served as a museum of sacral objects, including sculpture and vestments. The crypt, where the relics of Saint Andrew were held, was stunning with much ceiling and wall decoration.

Paper Museum at paper mill, Amalfi

I also was enamored with the still functioning paper mill at the Paper Museum. The Pope used paper made in Amalfi, which held the distinction of being the oldest paper manufacturer in Europe. The machines and the processes of making and drying the paper were enthralling.

Cathedral of Saint Matthew, Salerno

Salerno was a pleasant surprise. The Romanesque Cathedral of Saint Matthew hailed from the 11th century. The tower was a mixture of Byzantine and Norman styles. The central bronze door was made in Constantinople. Two Byzantine mosaic-decorated pulpits with intricate intarsia amazed in the once Romanesque interior that had been mostly transformed into Baroque style. Mosaics throughout the cathedral were stunning. Frescoes in the treasury chapels were accompanied by a silver statue of Pope Gregory VII. The Late Mannerist ceiling and wall frescoes in the crypt were remarkable, hailing from the middle of the 17th century. A reliquary of Saint Matthew’s arm was on display, too.

Diocese Museum, Salerno

I also visited the nearby Diocese Museum, which featured paintings, sculpture and objects from the Middle Ages to the 20th century. I was most drawn to the medieval altarpieces. The provincial picture gallery was small but included an eclectic array of intriguing works from the 15th to 18th century.

Cathedral of Saint Barbara, Kutná hora

Cathedral of Saint Barbara, Kutná hora

I took some day trips in the Czech Republic, too. We visited Kutná hora, the home of prosperous silver mines from the 13th to 15th century, during one stunning fall day. Saint Barbara’s Cathedral, with its Neo-Gothic exterior of buttresses and gargoyles, astounded me. Inside, I admired exquisite stained glass windows as well as remarkable late Gothic frescoes and a 16th century stone pulpit. The Gothic royal chapel with Art Nouveau decoration at the Italian Court was another remarkable gem.

Pub in Kersko

I visited Kersko twice this fall. I dreamed of owning a cottage in the tranquil, wooded village. I had lunch at the traditional Czech pub called Hájenka, where several films based on Bohumil Hrabal’s writings had been shot. Hrabal had lived in a cottage nearby for many years, feeding all the feral cats that would wander hungrily toward his home.

Zbiroh Chateau

I also toured the chateaus of Zbiroh and Karlova Koruna. Zbiroh, built before 1230, for decades served as a top-secret facility for the Czechoslovak army. Its representative rooms were open to the public only in 2005. The chateau boasted many Madonna statues and other sculpture of great interest as well as African masks, tapestries, Empire furnishings and copies of Leonardo da Vinci paintings. Alphonse Mucha had used the spectacular main hall as his studio early in the 20th century. A beautiful skylight, two Czech crystal chandeliers and impressive paintings adorned Mucha’s former studio.

Exterior of Karlova Koruna Chateau

Karlova Koruna Chateau, designed by Santini-Aichel and built during the 18th century, had a roof shaped as a crown. The chateau consisted of two stories in cylindrical shape with three one-floor wings. The interior featured paintings of horses, including the unique gold-colored horses that the Kinský family had bred as well as pictures of steeplechase races. One painting of a horse race was made of 12 pieces of deerskin.

Beneš Villa

We visited the former villa of Edvard Beneš, president of Czechoslovakia during the interwar years and a prominent member of the Czechoslovak governments-in-exile during the First World War. The stunning Neo-Spanish structure included the room where Beneš died, a dark landscape painting by Antonín Slavíček hanging over his single bed. The furnishings and artworks in the house were intriguing, to say the least. Beneš and his wife Hana were buried in a monumental tomb on the premises as well.

Sucharda’s Second Villa, Prague

In Prague I visited the second villa of sculptor and relief artist Stanislav Sucharda in the Bubeneč district. Jan Kotěra designed the structure with many architecturally intriguing elements. Much of the remarkable interior furnishings had been designed by Kotěra and Sucharda. I saw examples of Sucharda’s artwork as well as pieces by Edvard Munch, Auguste Rodin and many Czech artists.

Gallery of Modern Art, Hradec Králové, Work by Emil Filla

Gallery of Modern Art, Hradec Králové, Věra Jičínská, Brittany

I saw many impressive art exhibitions this year. I traveled to Hradec Králové, where I saw the Gallery of Modern Art with its impressive collection of works by 20th century artists including Bohumil Kubišta, Emil Filla, Jaroslav Róna, Ladislav Zívr, Quido Kočian and many others. The temporary exhibition of artist and writer Věra Jičínská’s works included paintings of her travels to Brittany and Paris. Her renderings of Paris showed off orange rooftops and the Eiffel Tower. She also created paintings inspired by folk art and dance. Her photography amazed me as well. Influenced by her work as a journalist, she created a painting dedicated to this genre.

Museum of East Bohemia, designed by Jan Kotěra, Hradec Králové

The museum devoted to the history of Hradec Králové was an architectural gem designed by Kotěra. I especially liked the furnishings and designs by Josef Gočár and Kotěra as well as the sculpture by Sucharda. The mock shops from the First Republic (1918-1938) were very intriguing as I could see goods that were sold during that era and feel the atmosphere of those times.

National Technical Museum, Prague

In Prague I saw the National Technical Museum for the first time. The cars, especially the 1935 Tatra 80 vehicle belonging to first Czechoslovak President Tomas G. Masaryk, fascinated me as did the motorcycles, bicycles and planes. The dining car of Habsburg Emperor Franz Joseph I, later used by President Masaryk, was also on display. I also was enamored by the architecture and engineering section and the display of old household items in another section. The TV studio, in use from 1997 to 2011, was another delight. Other areas of interest included astronomy, chemistry, printing, photography, time pieces, metallurgy and mining.

Museum of Czech Literature, book cover by Karel Teige

Another astounding sight in Prague was the newly-located Museum of Czech Literature, which moved to the Petschek Villa in Bubeneč during 2022. The displays cover literary developments from the 19th century National Revival movement through the 20th century. I came to appreciate the significance of the literary and art criticism periodical The Critical Monthly from the 1930s and 1940s as well as the symbolist and mystical paintings of Josef Váchal. I was most enamored by the avantgarde book covers designed by Karel Teige in the 1920s and 1930s. His unique typographical work in Vítězslav Nezval’s The Alphabet book was on display, too. A pantheon of great Czech 19th century artists included objects associated with the writers and their busts.

Karel Teige, Greetings from a Journey

A temporary exhibition focusing on Teige’s youth and early career from 1912 to 1925 was amazing, showing off his artwork, photographs, correspondence and more. I understood very well why this artist, writer, theoretician, critic, translator, book designer, typographer and photographer was considered the leading figure of the Czech avantgarde movement between the wars.

Trade Fair Palace, Prague, Fire by Josef Čapek

At The Trade Fair Palace in Prague, I saw the newly installed End of the Black-and-White Era permanent exhibition of art from 1939 to 2021 in chronological order. More than 300 works, mostly Czech, were displayed with historical context. Josef Čapek’s painting “Fire,” showing a fury of flames behind a woman, presents an anti-Nazi theme. The focus on urban life and factories as well as everyday life was highlighted with the works of Kamil Lhoták. The exhibition featured many works made during the Stalinization period of the 1950s with the style of social realism. Martin Slanský depicted Lenin in a snowy Prague. A model of the design of the monument to Stalin in Prague was on display, too.

Trade Fair Palace, Prague, The Dialogue by Karel Nepráš

The progressive movements of the 1960s made way for the red abstract figures of Karel Nepráš. From the late 1960s to early 1980s art as installation came to the forefront. Action art, performance and body art were often the focus of the times. The late 1980s triggered the impersonal postmodernism movement. After the 1989 Velvet Revolution that toppled the Communist regime in Czechoslovakia, individuality and quests for personal identity came to the fore. Some artists focused on the commercialization of society. This new exhibition was extensive and moving. I felt drawn into each historical period up to the present day. The works displayed well represented the movements expressed. I could see how society and culture kept changing and how art reflected those changes.

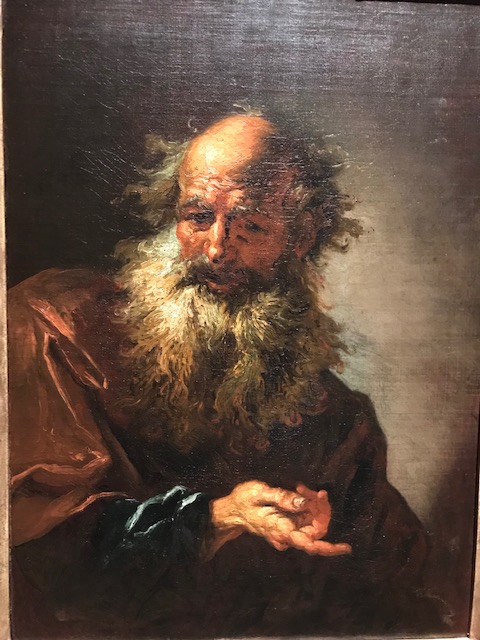

Saint Jerome by Petr Brandl

I went to many intriguing temporary exhibitions in Prague, too. I saw 64 religious works, genre paintings and portraits by Czech Baroque artist Petr Brandl. An extensive exhibition of Alphonse Mucha’s versatile works owned by his descendants included some originals never before put on display. Mucha’s ad posters, drawings, paintings, sculptures, photographs and jewelry all captured my undivided attention.

Sculpture by Janouch

I saw sculpture of athletes in motion and busts of illustrious Czechs by Petr Janouch in Prague’s Kooperativa Gallery. An earlier exhibition there featured Czech 19th and 20th century paintings involving water – puddles, lakes, waterfalls, streams, rivers and so on. I especially liked one painting by Josef Čapek showing a fisherman on a boat in a river. Landscapes with water themes by Slavíček and Antonín Hudeček also astounded.

Sculpture by Ivan Mestrovic

At the City Library Gallery I saw an exhibition of sculpture by Croatian Ivan Mestrovic (1883-1962). I had come across his art at his villa in Split during a vacation many years ago. Mestrovic, who had befriended first Czechoslovak President Masaryk and Czech sculptor Bohumil Kafka, had delved into a variety of styles, including Art Nouveau, Symbolism, Impressionism, Art Deco, Neoclassicism and late Realism, while preserving a Classical foundation. He focused on numerous themes – religious motifs, portraits and monumental works as well as studies of figures.

Olinka

However, shortly after I returned from the Amalfi Coast, I had to temporarily halt any traveling so I could be at home with Olinka, who was diagnosed with neurological issues that greatly affected her mobility. A MRI showed that she suffered from inflammation of the middle ear. A terrified Olinka spent a total of four nights in the hospital and was on antibiotics for ten weeks. Every two weeks we went to the vet so she could get her antibiotic shot.

Olinka

The first four days at home after three nights in the hospital she could hardly walk and was very disoriented. Those initial few days she stayed mostly in the bedroom closet, only appearing for food and the use of the litter box. She didn’t play with her toys for three weeks. Before her illness, I had been frustrated with Olinka because she always knocked everything off tables and the kitchen counter. Sometimes it felt like a never-ending battle. At the start of her illness, I came to appreciate even her most frustrating quirks. I just wanted her knocking everything off surfaces again, back to her old self. The broken glass on the screen of my mobile phone is proof that she is once again doing just that.

Olinka

I will never forget her first night back from the hospital. She somehow made her way onto the bed and reclined below my pillow. I rested next to her, my arms around her. We stayed like that for an hour or two, just spending time with each other, appreciating that she was alive and at home. I will always remember that feeling of relief and love more profoundly than any experience during my exciting travels.

Tracy A. Burns is a writer, proofreader and editor in Prague.

Olinka on Christmas Eve

From Alphonse Mucha exhibition

Municipal House, Prague, Mayor’s Hall, decoration by Alphonse Mucha

I toured the Municipal House in Prague. Once again, I was captivated by its Art Nouveau interior.