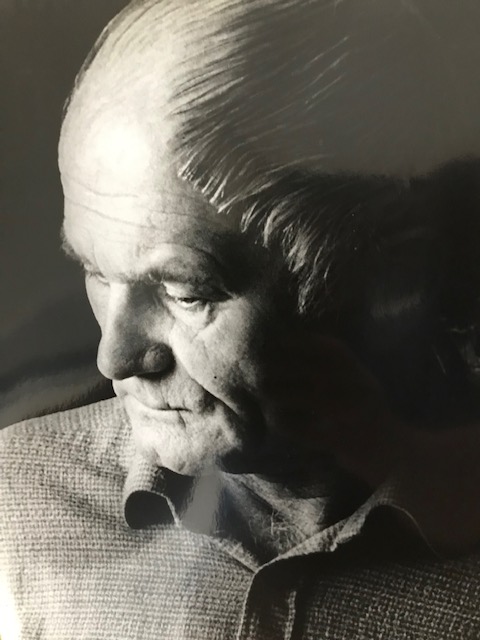

Czech legendary writer Bohumil Hrabal. Photo by Karel Kestner. Bought by me in Lesní atélier Kuba, Kersko some years ago.

For me Kersko is a sort of catharsis, easing my anxiety about daily life’s concerns and bringing me a sense of tranquilly. I feel at home here, even though I have no personal connection to this area not far from Prague. I can breathe in the clean air and be at peace with the world and myself. I would love to own a house in Kersko, a forested village dotted with traditional cottages and huge homes built by millionaires.

The Kersko restaurant Hájenka

Every now and then I made the trip to the village restaurant Hájenka, a traditional pub-like establishment with delicious Czech food. On the television in the pub, customers can watch scenes from late legendary Czech author Bohumil Hrabal’s film Snowdrop Festival. Some of the exteriors were shot at Hájenka while the interiors of the pub seen on the film were actually shot at a studio. Directed by the world-renowned Jiří Menzel and based on Hrabal’s 1978 novel, the stellar film remains a Czech classic with many unforgettable scenes.

One of many ceramic cat figures at Lesní atélier Kuba, Kersko.

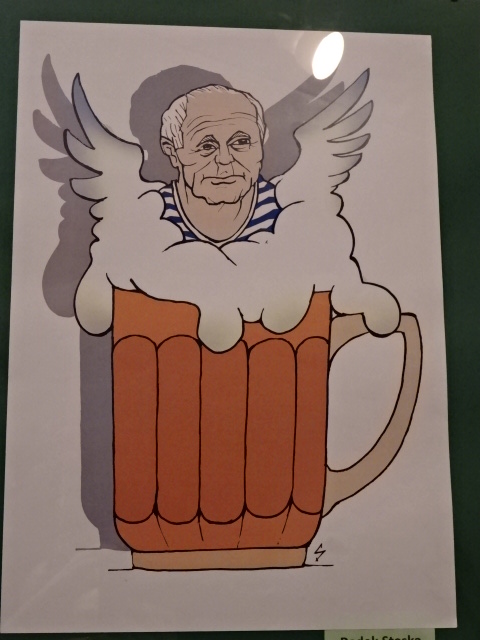

I also always stop at the souvenir and craft shop Lesní atélier Kuba, where beautiful handmade ceramic cats are sold along with other superb figures. The shop has been open since 1992. While a cat theme plays a major role in the inventory, there is much more to see. I always buy some of their delicious cookies. They sell much more than beautiful ceramics: t-shirts, postcards, books, candles and many other things. During my visit in May of 2024, the downstairs area was home to a fascinating temporary exhibition of witty drawings focusing on Hrabal’s life.

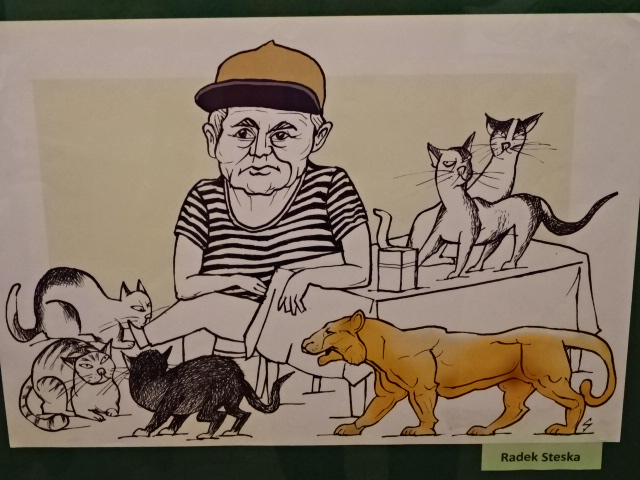

Drawing by Radek Steska showing Hrabal and his cats at The Golden Tiger pub in Prague, exhibited in Kersko at Lesní atélier Kuba.

Indeed, Kersko is intricately tied to the life and career of Hrabal, my favorite Czech writer and the name of my first cat. I penned my master’s thesis on his books, focusing on their historical context. From 1965 until his death in 1997, Hrabal often resided in a quaint, two-floor cottage in the village, fed the semi-feral cats, took walks, rode his bike and frequented the pubs, including Hájenka.

Bohumil Hrabal signing autographs in Spain during the mid-1990s. Photo property of Tracy Burns.

Born in the Austro-Hungarian Empire during 1914, Hrabal was renowned for his grotesque, absurd and irreverent humor and witty anecdotes. While he is mostly known as an author of fiction, he excelled at poetry early in his career. What I like best about his writing is his creation of the pábitel, a word connoting a dreamer living on the outskirts of society. Although the pábitel has experienced tragedy, he learns how to be content with life and how to find beauty in even the most horrid conditions. The pábitel often tells meandering, absurd anecdotes that make the reader both laugh and cry.

Bohumil Hrabal and Czech writer Arnošt Lustig in Golden Tiger pub, Prague during the 1990s. Photo property of Tracy Burns.

Hrabal held many jobs throughout his writing career. He worked as a train dispatcher in Kostomlaty, where he was almost killed by Nazi soldiers. Hrabal later was employed as an insurance broker and traveling salesman. After the Communist coup of 1948, he took a position at the Poldi steelworks in Kladno, but in 1952 a crane fell on him. Then Hrabal became a paper baler. He would later make a living as a stagehand in a theatre.

Bohumil Hrabal in photo taken by Karel Kestner, bought by me at Lesni atélier Kuba some years ago.

The year 1956 was very significant for Hrabal as he married Eliška Plevová, a German-Czech kitchen worker in Prague’s luxurious Hotel Paris. In 1965 they bought a cottage in Kersko. During the more liberal 1960s, Hrabal was able to spend more time writing, and he was even able to travel abroad. His 1968 film Closely Watched Trains, directed by Menzel, won an Oscar, based on the novel Hrabal had scribed three years previously.

Bohumil Hrabal in photo by Karel Kestner. Property of Tracy Burns and bought at Lesní atélier Kuba some years ago.

After the Warsaw Pact tanks crushed the Prague Spring of liberal reforms in 1968, Hrabal was banned as an author, and his works only appeared in illegal publications. During 1970 his book Buds (Poupata) was burned by the Communists. These were tumultuous years. Hrabal relented to intense pressure and signed the anti-Charter denouncing the Charter 77 document that called for human rights in Czechoslovakia, and he became an “official” author again. Yet his career was still not without its problems.

Bohumil Hrabal writing in photo by Karel Kestner. Photo property of Tracy Burns and bought at Lesní atélier Kuba some years ago.

During the 1980s, he wrote a famous trilogy that was part autobiography and part fiction, depicting times from the late fifties and the turbulent 1970s, for instance. In 1987 his wife died of cancer. He continued writing and traveled to the USA and Moscow at the end of the 1980s. In 1988 his legendary, long-time apartment on Na Hrázi Street in Prague’s eighth district was demolished to make way for the Metro station Palmovka.

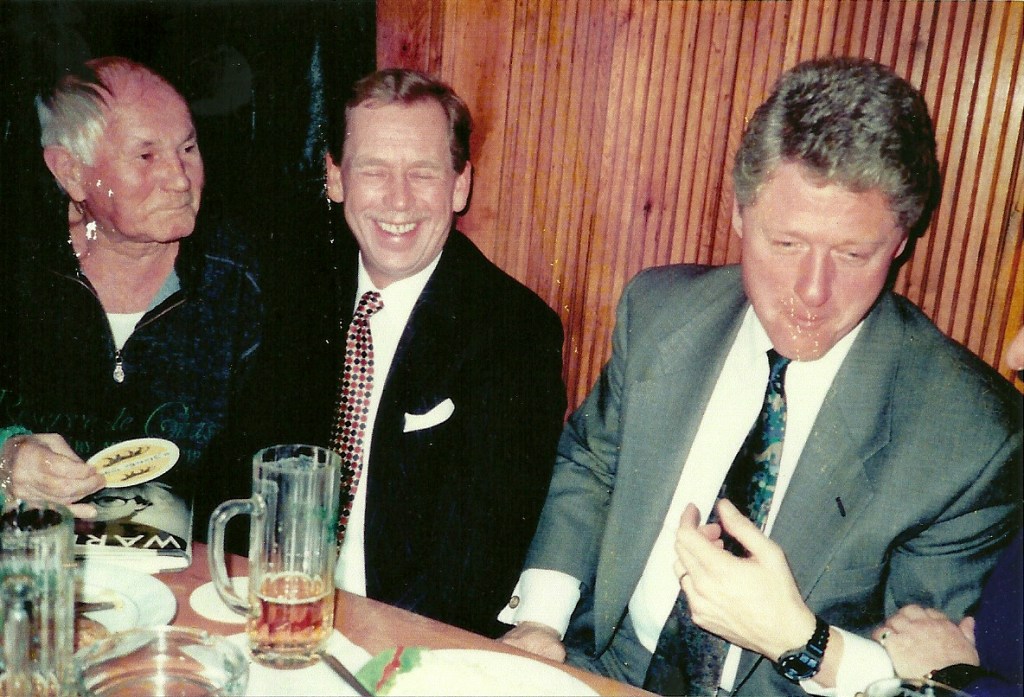

Bohumil Hrabal with then Czech Republic President Václav Havel and then US President Bill Clinton at The Golden Tiger pub, January, 1994. Photo property of Tracy Burns

In the 1990s, Hrabal could be seen drinking beer at the Golden Tiger (U zlatého tygra) pub in Old Town and traveling to Kersko to feed his many semi-feral cats. He won the Jaroslav Seifert prize during 1993 and accepted foreign literary awards as well as honorary degrees. He gave lectures and readings abroad. In January of 1994, the acclaimed author met then US President Bill Clinton and Ambassador to the United Nations Madeleine Albright at the Golden Tiger pub.

Drawing of Bohumil Hrabal by Radek Steska, exhibited at Lesní atélier Kuba in 2024

I first met Hrabal at the Golden Tiger pub in 1994, a few months after the author’s meeting with President Clinton and Ambassador Albright. He always ordered me fried chicken or pork steak because that is what President Clinton had eaten there. (I happened to like that food, too.)

Sometimes, he was in a cheerful mood and other times, he was angry and depressed. He could no longer take walks, something he had loved doing. Hrabal had to take a taxi to the pub. He often complained that his entire body hurt.

Cat sculptures in Kersko

At the end of 1996, Hrabal was hospitalized with neuralgia. He was about to be released when he jumped or fell from the fifth floor window on February 3, 1997. He is buried in the cemetery in Hradištko, near Kersko. The irregular gravestone is especially noteworthy for the sculpted arm and hand seemingly emerging out of the stone monument. The top square section of the gravestone has a circle in the middle. Many wooden and ceramic cat figures as well as beer bottles decorate the grave site. I like the gravestone. It is innovative and unique just as Hrabal had been.

Bohumil Hrabal’s grave in Hradištko

Kersko has an intriguing history. Hradištko was first mentioned in writing during the 11th century and at that time included a fortress called Keřsko. In 1376 Eliška from Lichtenburk acquired the territory. She was the grandmother of George of Poděbrady, who would become a Czech king. The fortress area expanded into a village between 1354 and 1357, but it was destroyed during the Hussite wars of the 15th century. A pond was later created on the site of the former fortress. At the beginning of the 20th century, archeological digs in the village unearthed Gothic weapons and other historical objects. Some trees in Kersko are over 200 years old. The oldest oak in Kersko is 193 meters high. The area includes three small ponds and a mineral spring as well as walking trails.

Some feral cats in front of Hájenka restaurant some years ago

Fast-forward to 1934, when private citizens were first allowed to buy property in Kersko. A café dominated by an octagonal tower was built the following year. Later, it would become the restaurant Hájenka. The village aspired to become a forest spa town. Plans were made to build a hotel, two swimming pools and a sports complex. Then World War II took place, and plans were stalled. The Communist coup of 1948 put a halt to the entire project. In the 1950s, small cottages cropped up in the picturesque lanes.

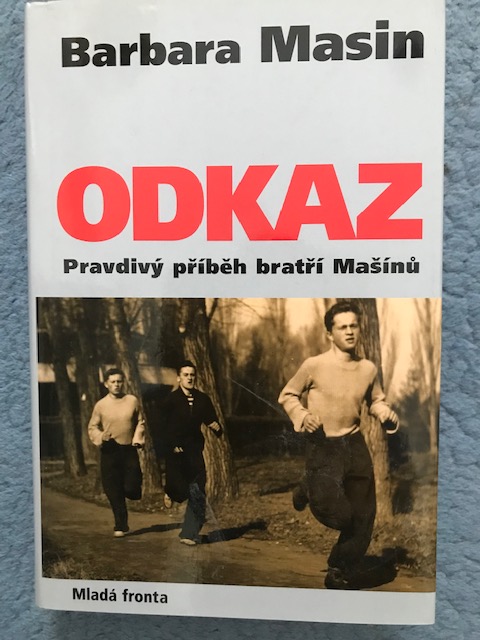

Odkaz, book about the Mašín brothers by Barbara Masin, published by Mladá fronta, 2005.

While Kersko is most famous for being the location of Hrabal’s cottage, it also made a name for itself in the history books long before Hrabal bought a home there, during September of 1951. The Mašín Brothers, an anti-Communist resistance group of young men who fought against the Communists from 1951 to 1953, made some stops in the Kersko forest. Members included Ctirad Mašín, his brother Josef, Milan Paumer, Zbyněk Janata and Václav Švéda. Their objective was to fight their way to freedom, and the two Mašín brothers and Milan Paumer were successful at doing just that in 1953 when they dramatically escaped to American territory in West Berlin. The armed group carried out violent attacks to get money for their cause. To be sure, the Mašín Brothers’ group is very controversial. Some consider them to be heroes who fought against the Communists while others claim they were murderers because they killed innocent people.

Čtyří české osudy, book about Mašín Brothers, by Zdena Mašínová and Rudolf Martin. Published by Ergo, 2018.

Back to their ties with Kersko: In the Kersko forest, Ctirad Mašín and Milan Paumer tied up a taxi driver and stole the cab in order to rob a police station in Chlumec nad Cidlenou. Two weeks later, three Mašín members came to Kersko in an ambulance they had stolen. They tied up the ambulance works in the forest. Then they robbed a police station in Čélakovice, using the stolen ambulance as transportation.

Guide book Odbojová skupina bratří Mašínů, about the Mašín brothers, by Jiří Padevět, published by Academia, 2018.

I had read and written about the Mašín Brothers’ group and was very interested in the anti-Communist resistance movement of the 1950s, so I found these facts to be very intriguing. I also was intrigued with the public’s perception of this armed group because some called them heroes, others cruel killers.

Bohumil Hrabal’s cottage in Kersko, photo from 2024.

Back to Hrabal. In May of 2024, I visited his cottage, which had recently opened to the public. Hrabal’s neighbor had inherited the cottage, and after a while the neighbor’s son sold it to the Central Bohemian Region, which did some reconstruction and made it look like it had during the 1980s. Some of the furnishings were original, some not.

Bohumil Hrabal’s cottage from the back. Photo taken in 2024.

The small, white, two-story structure had an exterior staircase leading to the enclosed balcony surrounded by windows with views of the big garden. Hrabal spent 18 days one July writing the novel I Served The King of England, seated in that garden. He loved to write on his typewriter in the garden.

Bohumil Hrabal’s cottage from one side. Photo taken in 2024.

We entered the tiny ground floor of the house, which was dominated by bunk beds and a table with three chairs. It served as a bedroom and dining room. Hrabal and his wife slept there when it was cold because the heater was in the space. He sometimes wrote in this room. In 1995 Hrabal wrote his last published piece here. I noticed that the date on the Svobodné slovy newspaper on the table was November 29, 1989, not even two weeks after the Velvet Revolution that brought the end of Communist rule. The hats and boxing gloves on a stand made of antlers were authentic. A small TV from the 1980s stood in a corner above the table. A collage by Karel Marysko was one intriguing artwork in the small space. The kitchen was tiny with a wooden stove and hot plate, for instance.

In the beautiful garden of Bohumil Hrabal’s cottage. Photo taken in 2024.

Upstairs there were only two spaces, much larger. Two single beds, decorated old chests and a closet were placed on a red carpet. I noticed the thick brushstrokes in the portrait of Hrabal by Josef Jíra, who was not only a painter but also a graphic artist and illustrator. He also frequented the Golden Tiger pub. The anxiety of people in the modern world often played a role in Jíra’s works. In the painting Hrabal looked sad and serious. Another painting, a collage, showed him in profile with logos of various beers, such as Pilsner Urquell, Primus and Prior. Another collage featured scenes and objects from the novel Cutting It Short, showing a brewery, an old record player and a couple dancing, among other pictures. I also saw portraits of Hrabal’s beautiful wife and parents.

Drawing of Bohumil Hrabal’s cottage with the semi-feral cats he feed, picture exhibited at Lesní atélier Kuba, 2024.

There were other paintings that caught my undivided attention. One showed a bright blue sea with two people looming above the water in a hot air balloon while a man and woman stood on the coast. The bright blue hue gave me a feeling of tranquillity. The drawing “A Loud Monologue” by Jiří Anderle included faces of Hrabal from early childhood to old age. My favorite picture showed Hrabal, sporting a scarf and hat, with cats seated on chairs in a forest. I knew that Hrabal considered his cats to be his children, which is one reason I named my first cat after him.

The street art memorializing Bohumil Hrabal’s home on the former site of Na Hrázi Street, Libeň, Prague, after his home there had been demolished to make way for the Palmovka Metro station.

The enclosed balcony was fabulous because it was so light and airy with views of the garden. I saw two typewriters and a large table with beer glasses and loose pages with handwritten corrections on it. Hrabal wrote here if the weather was bad. He penned Cutting It Short and The Snowdrop Festival here as well as many other works. I didn’t want to leave the balcony because it had such a calming effect on me.

Bohumil Hrabal’s cottage. Photo taken in 2024.

While Hrabal’s cottage was small, it had character. I could see him on the balcony writing while drinking glasses of beer or seated at the table downstairs playing cards or watching the small TV. I could feel his presence during the tour and realized how his writing was tied intricately to Kersko, a tranquil place where I feel at home and at peace.

Tracy A. Burns is a writer, proofreader and editor in Prague.

Bohumil Hrabal’s grave in Hradištko

Cats at Hájenka Restaurant some years ago